eBook - ePub

Available until 31 Dec |Learn more

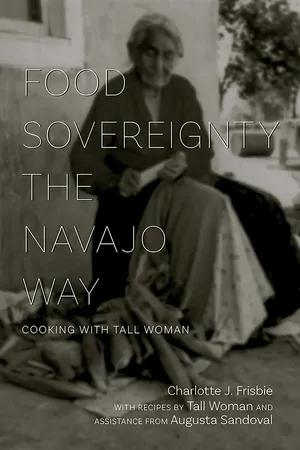

Food Sovereignty the Navajo Way

Cooking with Tall Woman

This book is available to read until 31st December, 2025

- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 31 Dec |Learn more

About this book

Around the world, indigenous peoples are returning to traditional foods produced by traditional methods of subsistence. The goal of controlling their own food systems, known as food sovereignty, is to reestablish healthy lifeways to combat contemporary diseases such as diabetes and obesity. This is the first book to focus on the dietary practices of the Navajos, from the earliest known times into the present, and relate them to the Navajo Nation's participation in the global food sovereignty movement. It documents the time-honored foods and recipes of a Navajo woman over almost a century, from the days when Navajos gathered or hunted almost everything they ate to a time when their diet was dominated by highly processed foods.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Food Sovereignty the Navajo Way by Charlotte J. Frisbie, Augusta Sandoval in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Customs & Traditions. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 | An Overview of the Navajo Diet and Navajo Dietary Research

ACCORDING TO NAVAJO oral tradition, Navajo ancestors emerged onto the present earth’s surface along with deities at Hajíínáí, the Emergence Place, not far north of present Navajoland.1 According to some accounts, specific Holy People ascended from the Lower Worlds, bringing certain implements and knowledge with them for the good of all. Although there are very few accounts of the origins of particular plants, corn is primordial, from time immemorial. It is divine, a gift of life, not a human creation. First Man and First Woman were transformed from two primordial ears of corn (Reichard 1963, 23, 433).

At least some of the foundational Emergence and Blessingway narratives credit Changing Woman with the creation of horses, sheep, and goats (Wyman 1970, 244–45). Goddard’s (1933, 128) account of the activities in the Lower Worlds notes that when the Yellow World became crowded, its inhabitants made five chiefs: large snake, bear, wolf, panther, and otter; these held a council and established clans. First Man said, “There will be hermaphrodites who will know women’s work and who will live like women. They will know the ways of both men and women.”

Other accounts attribute the creation of various kinds of wild and domesticated animals to the Sun and a supernatural being known as the Sun’s younger son, the invisible Moon Bearer, the “One who grabs breasts,” or Begochidí.2 The creations credited to these two include sheep, horses, swine, goats, mules, cows, fowl, deer, worms, and insects (Reichard 1963, 388–89; Matthews 1897). Begochidí is described as fair-skinned, red-haired, and blue-eyed and is sometimes viewed as the forerunner of Americans or Mexicans.

Some narratives credit various beings with bringing seeds from the Lower Worlds during the Emergence, and these seeds became the source of planting for both Puebloans and Navajos. Turkey is frequently mentioned, and the seeds are usually for corn, beans, and squash, among other plants. For example, Goddard (1933, 128) says that First Man, First Woman, and Turquoise Boy planted white, yellow, and blue corn, respectively, and then Turkey planted “brown corn, then watermelon seeds, muskmelon seeds, and last spotted beans.” Matthews (1897, 172–73) has Turkey shaking grains of white, blue, yellow, and variegated corn from its wings, followed by pumpkin (or maybe squash), watermelon, muskmelon, and bean seeds, four of each, each time. Wheelwright’s (1946, 12) Feather Chant account has Turkey shaking corn, beans, tobacco, and squash seeds out from under his wings.

Newcomb (1967, 38–41) credits Turkey with remembering to bring the seeds stored in big sealed storage jars as all living things ascended into the next world because of oncoming floods: “With no storage of food supplies, there would have been hunger and starvation during the winter” (40). As Turkey flapped his wings, out fell white, red, blue, yellow, and variegated corn; beans and sunflower seeds; squash, melon, gourd, onion, and pumpkin seeds; and also the small seeds of wild millet, wild rice, barley grass, tobacco, cane grass, mustard, and sage. Turkey was decorated with all that he had saved from the flood and brought from the Lower Worlds: the colors of corn, the brown of tobacco seeds, melon seeds on his feet, a bean vine on his forehead, soft feathers with sunflower pollen, and a beak with wild barley; the scales on his legs were the seeds of squash and gourds.

Haile (1981, 33–34) credits the nádleeh, the so-called transvestite or hermaphrodite, with the first squash, watermelon, and gourd seeds as well as a number of seeds for psychoactive plants. Some accounts also credit the nádleeh with making certain cooking tools in the Lower Worlds (Goddard 1933, 128; Matthews 1897, 70–72; Haile 1981, 33–34; Reichard 1963, 140–41). These include gourd dippers, grinding stones, pottery, hairbrushes, stirring sticks, water jars, earthen bowls and spoons, and baking stones. For example, Matthews credits the descendants of First Man and First Woman with making a great farm and creating plows from cottonwood boards, hoes, and stone axes but getting seeds from the Pueblos. The nádleeh, guarding the farm’s irrigation ditch, created pottery (a plate, bowl, and dipper) and a wicker water bottle.

Were I a Navajo trained in ceremonial knowledge and philosophy, and also of the conviction that such understanding should be shared in print so that today’s youth could theoretically have ready access to everything they need in order to live good lives in the future, this book would have been written from that perspective. But obviously I am not. I did have the good fortune to start learning about Navajo culture in graduate school in 1962 and then to continue learning through firsthand experiences. However, I am in no position to claim any kind of expertise about traditional Navajo points of view, nor will I ever be. I remain an outsider, an academic versed in anthropological training and perspectives who believes that both points of view should be included whenever possible.

Thus, I will present anthropological interpretations, except in a few cases in which my own earlier learning allows me to understand other perspectives or when ceremonialists who assisted me with this project told me something that they said I can share. Whether it would even be possible for interested Navajos to assemble knowledge today about the old foods, cultivated and wild, and the narratives associated with their creation and development is a major question. The same is true for assessing just how much of the knowledge that remains is still being transmitted to younger generations through the training of future ceremonial practitioners or through various school programs designed to help perpetuate Navajo language and culture.

In contrast to the Navajo origin explanations, anthropologists claim that Navajos descended from two main groups of ancestors: Athabaskans, who spread from Canada into the Southwest, and Puebloans, who occupied the Southwest for millennia. The Athabaskans lived off the land and survived mainly by foraging, perhaps adding a little farming as they moved south. The Puebloans were farmers. By the time of early Spanish contact in the 1500s, the ancestral Navajos were living by gathering, hunting, and a little farming. They would have had extensive, fine-tuned, shared knowledge of the environment, of all the plants and animals to be found therein, and of farming. By the 1600s, those nearest the Spanish settlements, at least, had added flocks of sheep and goats to their livelihood (Bailey and Bailey 1986, 11–17). This mixture of gathering, hunting, farming, and herding was the Navajo means of acquiring food through the late 1800s.

At this time the Navajos moved with their animals as necessary but also farmed whenever possible. The farming was usually dry farming (not irrigated), since permanently flowing water sources on their lands were few and far between.3 In time mutton became a primary part of their diet, and corn was also a major staple. Other crops the Navajos enjoyed and planted were melons and squash. In some areas, such as Canyon de Chelly, Arizona, it was possible to also grow fruit trees, such as peach, apple, and apricot trees. Elsewhere, beans could be grown.

Klara Kelley (personal communication, 2013), who has done extensive work with documents in the Navajo Land Claims Collection of the Navajo Nation Library, graciously contributed the following upon request:

Navajo elders interviewed circa 1960 recalled that food sources of their parents and grandparents in the mid-late 1800s included hunting, gathering, farming, and herding. In the driest part of Navajoland, the far southwestern section, people depended on herding more than farming, but everywhere else, elders emphasized farming more than herding. Crops were mainly corn and squash, with some melons and beans. Farms of many families were clustered together in places with the best runoff water. Wild game consisted mainly of deer, antelope, rabbits, prairie dogs, groundhogs, and sometimes porcupines, with bighorn sheep also mentioned for people of northern Navajoland, and turkey for those in the southwestern part. Wild plants most commonly mentioned were pinyon [pine] nuts, juniper berries, yucca fruit, wild grass seeds, various berries (wolfberry, sumac), wild potatoes, wild onions, wild carrots, greens (probably beeweed), tansy mustard, and goosefoot or amaranth, with mescal for people along the southern edge of Navajoland and wild walnuts and grapes for those in the southwest.4

Colonial governments also recognized Canyon de Chelly as the garden spot of Navajoland.

Readers familiar with Southwestern history know that shortly after US involvement in the region and the end of the Civil War, emphasis was put on ending raiding and other problems allegedly caused by the Navajos. After several skirmishes and military campaigns to destroy the Navajos’ crops, the US Army rounded up and marched many Navajos to Fort Sumner, New Mexico, where they were incarcerated (1863–1868). As many researchers point out, including Kopp (1986) and those at the Diné Policy Institute (DPI) (2014), unlike earlier incidents leading to changes, these events brought forced dietary adaptations and dependence on external food sources, many of which were nutritionally inferior to the Navajos’ traditional diet. Coolidge and Coolidge (1930, 272) list the following among the things the starving Navajos ate: “doves, rats, mice, prairie dogs, locusts, porcupine, badger, lynx, three kinds of greens, the inside of strawberry cactus, seeds, and roots.”

Many of the Navajo stories recorded by Johnson (1973) mention the foods available at Fort Sumner and, in a few cases, at the time of surrender before the Long Walk (the march to Fort Sumner). The food at surrender included bacon, white flour (frequently infested with vermin), and coffee (113). The food during incarceration included “rations” (which often meant coffee, flour, and sugar); cows and some pigs butchered by white men (and Navajos detailed to do such work), but never enough meat (which was also sometimes rotten) to go around (146, 191, 202); bacon, flour, corn, coffee beans (often said to be green), and sugar (119). Some stories also mentioned salt, baking powder, and other items (202) and said that the Navajos were shown how to use these products. Others listed dry corn, beans, acorns, and one slice of bread (238, 242, 243, 249–50). At least one mentioned people making clothes from flour sacks (215). As the accounts illustrate, many people died from ingesting a mush they made from flour and water or from eating the green coffee beans (214, 224, 229).

According to Eldridge (2012), this is when the Navajos started becoming dependent on the US government for food, especially the flour, sugar, and coffee she sees as the cornerstones of government food distributions. Eldridge, Tapahonso (1998, 7–10) and Iverson (2002, 65) attribute the origins of frybread (also called fried bread) to this period.

Even when the Navajos adopted foods from others, they often developed different ways of preparing them or discovered that by changing the cooking conditions they could turn them into something else. One clear example of the latter is the tortilla. A tortilla was made from the same dough used for making frybread, but for everyday use it was cooked on a dry skillet, on a griddle, or even on a wire mesh grill over coals outside. Stew was easily made by just adding potatoes to boiled mutton, since it was common to have few, if any, other vegetables. Although mutton stew became a food for special occasions, whether it was actually served depended on many factors, such as transportation, income, the availability of ingredients, and the preferences of the individuals involved.

The so-called American period (in contrast to the earlier Spanish and Mexican periods), which many start with the Long Walk and the incarceration at Fort Sumner, brought drastic changes to dietary habits, the environment, the economy, and just about every other aspect of Navajo culture. Government rations included some food items; seeds, mainly of corn and wheat (Bailey and Bailey 1986, 45); farming tools; and a certain number of animals, mainly sheep and goats. The Treaty of 1868 allocated more money for seeds and farming equipment than for livestock, and from the spring of 1869 until 1879, when original payments ended and even later when they resumed with different funding, seeds and equipment were emphasized.

The seeds were for crops already familiar to some Navajos—such as beans, watermelons, muskmelons, squash, and pumpkins—as well as for new crops: turnips, beets, sugar beets, spinach, cauliflower, parsley, asparagus, rutabaga, and potatoes. Of the new crops, only potatoes took hold. The equipment available from the government consisted of hoes, sickles, spades, mattocks, and axes (Bailey and Bailey 1986, 46), with shovels and pickaxes being added in the 1870s and plows in the 1880s. The Navajos preferred to use their traditional farming methods and their digging sticks but eventually added hoes, shovels, plows, and rakes. Of course, the intensity of the farming varied from place to place, depending on climate and the flood-waters available for irrigation.

When the Navajos returned from Fort Sumner in 1868, Hispanic and Anglo settlers had taken control of the Navajos’ best hunting and gathering lands, the uplands around the edges of Navajoland. With farming places in their remaining lands also limited, the Navajos had to be creative about food sources, especially in 1868–1878. Some increased their reliance on hunting, almost pushing antelope and elk herds into extinction. They solved their need for hides for making moccasins with requests for hides from ration beef cows. The Navajos also continued gathering roots, nuts, fruits, bulbs, seeds, and leaves of wild plants (Franciscan Fathers 1910; Matthews [1902] 1995; Elmore 1943).5 Pinyons were important when plentiful; one report of diet in 1881 lists them along with acorns, grass seeds, sunflowers, wild potatoes, and the inner layers of the pine tree (Bailey and Bailey 1986, 49). Some Navajos depended more on herding, both as a food source and for something to exchange at trading posts for mass-produced foods (Kelley and Whiteley 1989). And before about 1872, they did resort to some raiding of their Hispanic, Anglo, and Pueblo neighbors for food (Bailey and Bailey 1986, 30, 38–39).

As many of the scholars cited here note, the Navajos were recovering their earlier self-sufficiency by 1880 because of the judicious management of their livestock, their willingness to try new ration items, and their recognition of other uses for the available items. For example, until 1878, pans, pails, plates, cups, kettles, and dippers were common government-issue items; the available blankets could be unraveled for yarn; wool and wool cards could be requested; and laborers could request pay in Mexican coins instead of food in order to obtain silver for silverwork.

In the latter part of the nineteenth century the economy changed significantly—first with the arrival of trading posts and traders, which actually started in the late 1860s, and then with the advent of the railroad in the 1880s (which took rangeland and water sources while bringing good and bad components of Anglo culture to the Navajos).6 These stores could stock products unknown earlier to some of the Navajos, such as tea, salt, white flour, sugar, coffee, baking powder, rice, calico cloth, tools, and manufactured goods.7 Traders became the source for many of the earlier ration items, and the Navajos, using their weavings, wool, jewelry, and livestock—through barter, pawn, credit, and cash—could acquire foodstuffs, tools, calico cloth, and other manufactured items. It was clear that some Navajos had also become proficient at blacksmithing, having learned ironwork from the Spanish. Trading post inventories varied with regional or local preferences and needs. Canned goods, fruit, smoked meat, and clothing for men were common (Russell 1991).

The Twentieth Century

People interested in the Navajo diet over time can be grateful that for the period beginning in the 1900s, we can turn to the work of Wendy Wolfe (1981, 1984).8 In the sections that follow, I have, with her permission, depended mainly on her work, which extends to the early 1980s; where appropriate, it is augmented by data from others, including Carpenter and Steggerda (1939), Steggerda and Eckardt (1940), Bailey (1940), and my own experiences.

1900–1920

At the turn of the twentieth century, the Navajos were sustaining themselves through a combination of pastoralism, horticulture, the gathering of wild plants (such as wild spinach, pinyon nuts, yucca fruit, and berries), and the hunting of small animals (such as rabbits and prairie dogs). The traditional diet with which the Navajos began the new century has been praised by contemporary researchers, since as Wolfe, Weber, and Arviso (1985) and others have shown, the traditional diet included foods from each of the four basic groups, and unlike today’s diet most traditional foods were nutritious. Bread and cereal provided fiber, iron, and vitamin B-complex (and, with culinary ash, minerals such as calcium). Fresh and dried wild plants, fruits, and berries were common and, in time, were joined by cultivated squash and melons. The fruits and vegetables provided vitamins A and C, fiber, and other necessary elements. Meat, both wild and domesticated (and including almost all parts of some animals) provided protein, iron, and other minerals. Pinyon nuts and seeds from squash and tumble mustard also provided protein. Milk and cheese from sheep and goats provided calcium, but an even more important source of that was culinary ash and clay.

Generally,...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 | An Overview of the Navajo Diet and Navajo Dietary Research

- 2 | Subsistence Practices in Tall Woman’s Family

- 3 | Defeating Hunger by Making Something from the Earth: Cooking with Tall Woman

- 4 | Reflections

- Appendix A | The Commodity Food Program

- Appendix B | A History of Restaurants in Chinle, Arizona

- Notes

- Glossary of Navajo Words

- References

- Index