eBook - ePub

Available until 31 Dec |Learn more

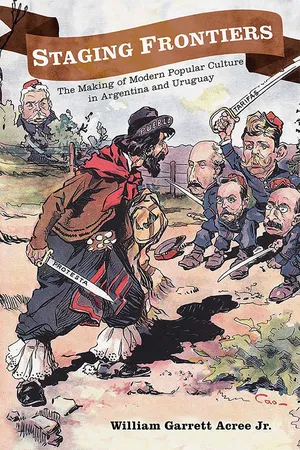

Staging Frontiers

The Making of Modern Popular Culture in Argentina and Uruguay

This book is available to read until 31st December, 2025

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 31 Dec |Learn more

Staging Frontiers

The Making of Modern Popular Culture in Argentina and Uruguay

About this book

Swashbuckling tales of valiant gauchos roaming Argentina and Uruguay were nineteenth-century Latin American bestsellers. But when the stories jumped from the page to the circus stage and beyond, their cultural, economic, and political influence revolutionized popular culture and daily life.

In this expansive and engaging narrative William Acree guides readers through the deep history of popular entertainment before turning to circus culture and rural dramas that celebrated the countryside on stage. More than just riveting social experiences, these dramas were among the region’s most dominant attractions on the eve of the twentieth century. Staging Frontiers further explores the profound impacts this phenomenon had on the ways people interacted and on the broader culture that influenced the region. This new, modern popular culture revolved around entertainment and related products, yet it was also central to making sense of social class, ethnic identity, and race as demographic and economic transformations were reshaping everyday experiences in this rapidly urbanizing region.

In this expansive and engaging narrative William Acree guides readers through the deep history of popular entertainment before turning to circus culture and rural dramas that celebrated the countryside on stage. More than just riveting social experiences, these dramas were among the region’s most dominant attractions on the eve of the twentieth century. Staging Frontiers further explores the profound impacts this phenomenon had on the ways people interacted and on the broader culture that influenced the region. This new, modern popular culture revolved around entertainment and related products, yet it was also central to making sense of social class, ethnic identity, and race as demographic and economic transformations were reshaping everyday experiences in this rapidly urbanizing region.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Staging Frontiers by William Garrett Acree in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Latin American & Caribbean History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1

A Cultural History of Popular Entertainment (1780s–1880s)

CHAPTER 1

Royal Impressions and Patriotic Diversions

The Social World of Entertainment

Some 120 miles east, across the Río de la Plata, another Englishman by the name of Alexander Caldcleugh made a stop in Montevideo on his trip from Rio de Janeiro to Buenos Aires in early 1821. The governor’s office received him well, and the evening of his arrival he attended the city’s sole theater. Despite the good food he was served and the conversation with “all the most celebrated beauties of the city, who were extremely polite,” he described the theater itself as “small and ill arranged; the actors, it may be supposed, not of the best.” And even though the “well dressed women in the streets” and at the theater left a more positive impression on Caldcleugh, he held firm in his higher opinion of theaters in London and Paris.2

Aside from scoffing at the theater, such accounts point to a simple fact: prior to the 1830s formal entertainment options in the region were limited. A handful of theaters offered inhabitants—particularly the more well-off—a place to see and be seen, as well as a small number of fairly poorly presented plays, if we are to believe Sánchez and the Englishmen. Plazas de Toros were another formal performance space on both sides of the Plata river, though bullfights were much less common than in Spain, New Spain, or other parts of the Spanish empire in America. Despite the scarcity of formal venues, there was an increasing environment of popular spectacle that developed between the late 1700s and the 1820s, revolving initially around religious and royal celebrations, and then gathering force with the wars of independence, patriotic commemorations, and entertainment in public spaces.

If one were to live long enough to be able to tour the social world of entertainment from roughly 1780 to 1830, the half century corresponding to the transition of the Río de la Plata region from its colonial frontier days to an emerging commercial area comprising two independent republican nations, several stops would be imperative. The first of these would allow for vivid observation of royal ostentation and the presentation of religious zeal, forms of spectacle that more often than not went hand in hand until the crisis of the Spanish monarchy shook the colonial order in the early 1800s. A second extended stop would reveal nativist undercurrents that begin to permeate forms of entertainment both inside and outside of the theater as early as the decade of 1780. More precisely, such undercurrents materialized in the first examples of gauchesque drama, and they remained an important vehicle of communication during the wars of the 1810s. This nativist spirit meshed with the patriotic messaging of independence. A final, overlapping vista comes from the back and forth between the silly and the serious. That is, serious representations of political, military, and religious power often found expression through or alongside more silly acts. This abstract concept was on the minds of the first theater entrepreneurs. Thus, Manuel Cipriano de Melo, who financed Montevideo’s Casa de Comedias, had the slogan “Through laughter and song, theater improves behaviour” embroidered onto his theater curtain. Gauchesque poet and theater director Bartolomé Hidalgo fused humor and country wit together in his dialogue between two gauchos who paint a seriously patriotic portrait of the 1822 fiestas mayas, or civic celebrations, honoring May 1810 when the push for independence got its start in the region.3 Finally, a game of sortija, which was basically horseplay (more on this below), was never temporally or geographically far from the more solemn masses or military parades that took place on a regular basis throughout this period.

In this chapter we will undertake this tour as a point of departure for understanding the emergence of popular spectacle in the region during the half century in focus. The stops highlight transformations in forms of spectacle as well as their rules of social engagement. The transition from religious to secular entertainment resulted in not only a proliferation of the types of entertainment activities but also modified forms of sociability associated with these. Before the 1810s, the theater was one of the few public diversions for women, whereas men had other sites they frequented, such as cockfights and horse races. In Montevideo, so common was it to see women and their children at the theater that complaints of screaming kids are frequent in local press reviews of the performances. Of course, women and men in Montevideo, Buenos Aires, and in sleepier towns of the interior yearned for ways to escape the boredom of daily routine. Entertainment provided this escape.4

Before beginning our tour of the early social world of entertainment, one caveat bears underscoring. The goals and nature of entertainment no doubt underwent substantial transformation as political representation and forms of power shifted from monarchical control to republican institutions. Royal authority gave way to incipient republican, state oversight and appropriation of forms of popular spectacle. At the same time, the shifting political character of entertainment started to evidence growing distance between a formal state connection and the world of entertainment. This point is critical to bear in mind. Moreover, participation in the social world of entertainment brought people together in more and different ways. However, this burgeoning atmosphere of popular spectacle did not usher in a radical reshaping of the social hierarchy in the region. Men, women, free blacks, slaves, children, and peasants did mingle more thanks to entertainment options. But these people also “knew their place,” even if that place was increasingly less fixed.

Royal Ostentation and Religious Zeal

When the Bourbon reforms led to the creation in 1776 of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, encompassing today’s Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Uruguay, as part of the Spanish crown’s effort to shore up control in the Southern Hemisphere, Buenos Aires and Montevideo were just sparsely populated frontier contraband ports.5 The official census of Buenos Aires in 1778 reported a population of around twenty-five thousand, though as Lyman Johnson has shown, the real number of inhabitants was higher. Even as the region’s most populous city, Johnson points out that “in 1780 Buenos Aires was the least distinguished viceregal capital in Spain’s American empire.”6 However, the decision to make Buenos Aires the capital of the new viceroyalty changed the trajectory of the city and the region.

From roughly 1780 to 1810, there was significant demographic growth, construction, and an uptick in economic activity. By the 1810 census, the population of Buenos Aires had swelled to more than forty thousand. A broad mixture of groups, including startling numbers of African slaves and their descendants, recently arrived European immigrants, and migrants from the region’s countryside, contributed to the new social architecture, as well as to the expanding urban infrastructure.7 The hub of this urban expansion was the Plaza Mayor (today’s Plaza de Mayo), the political, religious, and military center of Buenos Aires, as well as the epicenter of the city’s ceremonial activity. There the whitewashed Cabildo looked east across the Plaza to the fortress. On the north side of the Plaza the new cathedral was under construction. And in the Plaza itself, a makeshift market formed daily with foodstuffs and artisans’ wares for sale. Travelers complained of the marketplace becoming a central swamp when it rained, while Cabildo members harped about butchers moving their products into the halls of the government building.8

By the end of the 1700s, the city center had started to experience a facelift, with new homes constructed of sturdier materials, and some brick- or stone-paved streets, though these were the exception.9 Parish church steeples pierced the skyline.10 A visitor from the United States commented on these features, noting that from the river the city’s “domes and steeples, and heavy masses of buildings give it an imposing, but somewhat gloomy aspect.”11 At night most of the city’s buildings and streets were dark. The Teatro de la Ranchería, thought of as a temporary locale that would help fund an orphanage, opened for performances at the end of the 1770s as the city’s first formal theater. It was located at the intersection of Perú and Alsina Streets, about two blocks from the Cabildo and the Plaza Mayor. The viceroy asked the theater’s neighbors to place a light in their doorway so that spectators would feel comfortable when leaving the show after nightfall.12 The Ranchería offered denizens a new entertainment outlet, but its spectacles did not compete with either royal or religious pomp and circumstance.

Montevideo at the turn of the nineteenth century shared many of the same characteristics as Buenos Aires, though on a smaller scale. The town’s population numbered less than half that of Buenos Aires on the eve of the nineteenth century, though its growth kept pace with the expansion of Buenos Aires, and it was the most populated area of the Banda Oriental, the territory that would become Uruguay.13 The demographic makeup was similar, too: Afro-descendants constituted close to 30 percent of the population, substantial numbers of Spanish and Portuguese migrants settled in the city as economic opportunities opened up, and migrants from the countryside relocated to the port town in search of work.14 The core of the city (today’s Ciudad Vieja) was compact, with an urban layout similar to Buenos Aires: Cabildo and Cathedral faced each other across the newly designed Plaza Mayor—the town’s nerve center—set roughly in the middle of a tight grid layout, and parish churches marked other distinct points of the cityscape. The Casa de Comedias, which opened in 1793, was a couple of blocks south within the city’s fortified walls. While both Buenos Aires and Montevideo were perched on edges of seemingly endless plains, Montevideo was erected on a peninsula that jutted out into the river. The advantage was that it sat on a natural harbor that was deeper than Buenos Aires’s, accommodating larger ships and making unloading at the shore possible.15 The smaller town was also more strategically located vis à vis the entrance to the Río de la Plata, which made it a crown jewel in the control over access to South America from the South Atlantic.

Though the strategic allure of Montevideo and the region’s commercial prospects were not lost on the British navy, which invaded the region twice (1806 and 1807), travelers were more ambiguous about their impression of the city. In a series of letters fit for a soap-opera tale, the Englishman John Constance Davie wrote about his forced arrival in South America in 1797, en route to Australia. He landed at Montevideo and was curious to see the town, “though, God knows, besides the river and the mountain there is but little to excite the traveller’s curiosity.”16 Twenty years later, at the beginning of the Luso-Brazilian occupation of the Banda Oriental, Henry Brackenridge dashed a similar appraisal of Montevideo, writing that from the bay the town gave “no mean appearance.” Once on land, though, he expressed surprise at the devastation war had caused. There was an eerie quiet in the city center, with rough-looking types sleeping on thresholds—though he admits this may be due to the hour of his stroll, during the siesta. Brackenridge attributed the decline of the city’s activity to the “barbarian” José Artigas, who led a series of sieges of the city in a bid to overthrow Spanish control.17

That most of the region’s population was concentrated in Buenos Aires and Montevideo helps explain why interior towns were less central to the performance scene that emerged, and why documentation is scarce for interior cities, except places like Córdoba or Colonia del Sacramento. Moreover, this sketch of the population distribution and the cityscapes of Buenos Aires and Montevideo at the turn of the century makes it easy to see how these cities could feel like frontier towns where boredom could easil...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Heterogeneous, Mundane, and Transformative

- Part 1 A Cultural History of Popular Entertainment (1780s–1880s)

- Part 2 Equestrian Showmen Onstage and Off (1860s–1910s)

- Part 3 Consolidating the Popular Culture Marketplace (1890s–2010s)

- Curtain

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index