- 343 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book represents voices of resistance from across the globe to document the communicative processes, practices, and frameworks through which neoliberal global policies are currently being defied. Based on examples, case studies, and ethnographic reports, Voices of Resistance serves as a space for engaging various perspectives from the global margins in dialogue. The emphasis of the book is on the core idea that creating spaces for listening to voices of resistance fosters openings for the politics of social change-interweaving the stories of the local, the national, and the global. The book is divided into chapters addressing the politics of resistance in the contexts of global economic policies, agriculture, education, health, poverty, and development.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Voices of Resistance by Mohan J. Dutta in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Comparative Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Introduction: Voices of Resistance

This book is set up as a primer that attempts to foreground the voices of social change that make up the current landscape of global politics of resistance, and that define the discursive spaces, processes, structures, and constructions of social change efforts across the globe. These current forms of social action spread throughout local sites in different parts of the globe offer us guiding frameworks for understanding the ways in which disenfranchised communities and the people residing in these communities are seeking to transform the political, economic, and social configurations that have excluded them. Although the issues that are taken up by these efforts of social change vary widely, what lies common to them is their emphasis on opening up opportunities for communication, recognition, representation, and community participation in local, national, and global decision-making processes (Bello, 2001; de Sousa Santos, 2008; della Porta, 2009; della Porta & Diani, 2006; Giugni, 2002, 2004; Giugni, McAdam, & Tilly, 1999; Guidry, Kennedy, & Zald, 2000; Johnston & Noakes, 2005; Langer & Muñoz, 2003; Lucero, 2008; Mayo, 2005; Meyer & Whittier, 1994; Moghadam, 2009; Smith, 2002, 2004; Smith & Johnston, 2002; Starr, 2005; Tarrow, 2005; Waltz, 2005). Therefore, at the heart of the theoretical framework that I will elucidate throughout the different chapters of this book is the concerted emphases of these various social change processes on opening up communicative spaces for participation, recognition, representation, and dialogue, in ways that create possibilities for listening to the voices of subalternity1 within mainstream structures of policy and program articulation, shaping the material realms of policy making and program planning (Bello, 2001; Dutta, 2011; Dutta & Pal, 2010, 2011; Ferree & Tripp, 2006; Frey & Carragee, 2007; George, 2001). Because the politics of representation lies at the very heart of these communicative struggles of resistance across the globe, the voices from the global margins seeking to transform the underlying communicative inequities are at the center of this book, working in solidarity to offer directions for structural transformation. As a strategy of disruption, I will seek to center the voices of resistance engaged in these various global struggles, although these voices are constituted in dialogue with my subjectivity as an academic interested in the emancipatory politics of social change.

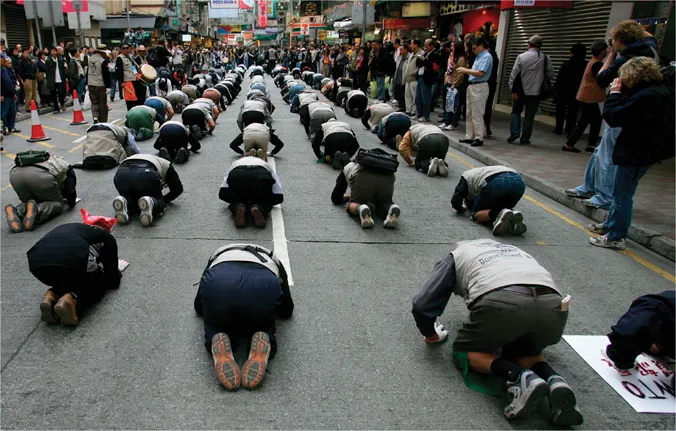

Figure 1.1. South Korean farmers demonstrate against the World Trade Organization on December 15, 2005 (Photo by Guang Niu, iStockphoto, contributed by EdStock).

Communication Studies scholars have long studied resistance in various contexts of communication (Alvesson & Deetz, 2000; Cloud, 1994; Dutta & Pal, 2007; Dutta-Bergman, 2004a, 2004b; Mumby, 2005; Pal & Dutta, 2008), documenting the discourses and discursive processes at micro, meso, and macro levels that oppose the power and control written into the dominant structures of organizing. Whereas a large body of research on resistance has drawn on the fragmented discourses in everyday practices that resist the oppressions constituted in dominant structures, other lines of research have interrogated the emphasis on micro-practices of resistance and instead suggested the importance of examining the dialectical tensions between the discursive and material aspects of resistance against structures of oppression (Cheney & Cloud, 2006; Cloud, 1994; Dutta, 2009, 2011; Zoller, 2005). Yet more recent research in Communication Studies notes the Eurocentric logics that permeate scholarly examinations of resistance, and instead argues for the development of postcolonial and Subaltern Studies approaches to the study of communication that foreground the voices of resistance in the global margins (Broadfoot and Munshi, 2007; Dutta, 2009, 2011; Dutta-Bergman, 2004a, 2004b; Munshi, 2005; Pal & Dutta, 2008a, 2008b). The culture-centered approach joins the voices of postcolonial and Subaltern Studies scholars in Communication Studies and elsewhere to deconstruct the logics of erasure that silence subaltern representation in dominant public spheres in the global North/West where policies are configured and then carried out locally through collaborations with the local elite (Dutta, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2011). The politics of culture-centered work therefore lies in the precise moment of solidarity between academics at discursive sites of power with subaltern communities in the global margins in configuring a co-constructed politics of representation that opposes the dominant structures of oppression by rendering visible the hypocrisies underlying these structures and by articulating alternatives for local, national, and global organizing of resources that are based on alternative values and rationalities.

Therefore, resistance is understood in terms of the cultural, social, political, and economic processes that are directed at transforming the global structures of material inequities and the communicative inequities that accompany these global structures (Dutta, 2008, 2009, 2011, in press a, in press b; Dutta & Pal, 2010, 2011; Pal & Dutta, 2008a, 2008b). Particularly paying attention to the inequities in communicative structures and the efforts of change that are directed at fundamentally changing the processes and configurations of communication, the thesis of this book is driven by the culture-centered approach to communication for social change (Dutta, 2008a, 2008b, 2008c, 2011; Dutta-Bergman, 2004a, 2004b). The culture-centered approach to communication for social change focuses on the inequities in the opportunities for participation in communicative processes and spaces, and puts forth the argument that essential to the processes of structural transformation is the transformation of communicative structures, infrastructures, processes, rules, strategies and techniques that erase subaltern voices (Dutta, 2011, in press a, in press b; Dutta & Pal, 2011; Pal & Dutta, 2008a, 2008b).

Attending to the historic and contemporary differentials in access to communicative sites where articulations are made, policies are passed, and programs are implemented, culture-centered research documents the discursive processes and messages through which these differentials are maintained (Dutta, 2008c; Dutta-Bergman, 2004a, 2004b; Dutta & Basnyat, 2008a, 2008b, 2008c; Pal, 2008). Essential to the reproduction of these differentials is the privileging of certain forms of knowledge and knowledge claims and the simultaneous “othering” of other forms of knowledge claims as backward or primitive. Along with the primitivization of specific processes and forms of knowledge, the sites at which these processes and forms of knowledge are enunciated are marked off as outside the normal realm of participation. Discursive strategies of dichotomization are essential to the logics of (neo)colonization that carry out projects of marginalization by couching neoliberal projects in the languages of development, modernization, and in more recent times, liberalization and industrialization. The primitive other from the Third/South/Underdeveloped spaces emerges into discursive spaces of (neo)colonization as the agency-less subject in need for being saved by the dominant actors in the First/North/Developed sectors.2 The language of culture emerges into the discursive spaces of development to describe and categorize the “other” as a subject to be managed and controlled under the logics of globalization (Dutta, 2011, in press a, in press b; Dutta & Pal, 2010, 2011; Sastry & Dutta, 2011a, 2011b; Escobar, 1995, 2003). It is this precise framing of culture as primitive and static underlying development interventions that is resisted in the culture-centered approach by foregrounding the dynamic, contextually situated, and active role of culture as a site for constructing alternative epistemologies that offer alternative rationalities for organizing life worlds (de Sousa Santos, 2008; de Sousa Santos, Nunes, & Meneses, 2008; Dutta, 2008, 2011, in press a, in press b; Shiva, 2001; Shiva & Bedi, 2002).

In the culture-centered approach, communication for social change seeks to change the inequitable structures that limit the possibilities for communication (Dutta, 2009, 2011; Dutta-Bergman, 2004a, 2004b, 2004c, 2004d, 2005a, 2005b; Dutta & Basu, 2007a, 2007b; Pal & Dutta, 2008a, 2008b). The material margins are defined, produced, and reproduced through communicative processes that mark the margins as backward and incapable of participation, and simultaneously erase those from the margins from the mainstream policy platforms, juridical structures, and platforms of decision making (Dutta, 2011; Kim, 2008; Pal, 2008). At the root of the processes of communicative marginalization is the economic inaccess to sites of power amidst mainstream structures that therefore dictate the rules, languages, techniques, and procedures for communicative participation. The consequence of communicative erasure is the further economic disenfranchisement of those in the margins, through the development of policies and programs that concentrate economic wealth in the hands of the dominant structures and simultaneously foster exploitative relationships with the margins. The relationship between symbolic and material marginalization therefore is twofold: on one hand, symbolic marginalization happens because of material marginalization; on the other hand, it is because of symbolic marginalization that material marginalization is perpetuated. Underlying the politics of resistance therefore is the necessity to disrupt this cyclical relationship between symbolic and material marginalization (Cheney & Cloud, 2006; Cloud, 2005; Dutta, 2011, in press a, in press b; Pal & Dutta, 2008b, 2010, 2011). These forms of resistance, I will argue through the presentation of examples that are woven throughout the book, are built on the idea that the margins are in essence fostered through logics of communication that limit the communicative opportunities for participation and voice. By listening to the voices of resistance constituted in the global margins, possibilities of structural transformation are introduced within the dominant spheres of knowledge production that have carried out the marginalization of the subaltern sectors through the delegitimization of the agency of local communities. Localized community participation emerges as a site for resisting the top-down control enacted by neoliberal forms of governance imposed through structural adjustment programs (SAPs) (Bello, 2001; Dutta, 2011, in press a, in press b; Johnston, 2009; Olivera, 2004; Shiva, 2001).

With the increasing inequities globally that have accompanied the processes of neoliberal reforms pushed across the various sectors of the globe (Millen & Holtz, 2000; Millen, Irwin, & Kim, 2000; Navarro, 1999), there have been increasing public participation in processes of social change, demanding for social justice and equity, evident in the Seattle protests in 1999, and the World Social Forums (Johnston, 2009; McAdam, McCarthy, & Zald, 1996a, 1996b; McAdam, Tarrow, & Tilly, 2001; Moghadam, 2009; Smith, 2002; Smith & Johnston, 2002; Tarrow, 2005). As the global centers of material wealth have increasingly consolidated powers in their hands through the co-optation of the state, civil society, and international networks to serve their agendas of wealth accumulation, the discursive spaces and communicative sites of participation have been dramatically reduced, having been constrained in the hands of the powerful political economic actors with access to global resources (Dutta, 2011). Under the name of promoting freedom and liberty, the language of the market has taken precedence, and has simultaneously carried out both physical as well as structural violence on communities at the margins through top-down programs of neoliberal governance that are imposed on communities without their participation (Dutta, 2008a, 2008b, 2011; Dutta & Basnyat, 2008a, 2008b). Communicative processes therefore have been increasingly limited in offering avenues for participation to the disenfranchised communities of the globe, ironically juxtaposed in the backdrop of the dramatic rise in participatory projects in international financial institutions (Bello, 2001; Dutta, 2011, in press a, in press b; Sachs, 2005; St. Clair, 2006a, 2006b; World Bank, 2001, 2002). The irony of neoliberal governance lies in the mismatch between the languages of participation and democracy that are widely circulated in order to push for neoliberal reforms that further disenfranchise the poor and the middle classes, and the ongoing erasures of actual opportunities for participation of the poor and the disenfranchised sectors in local, national, and global processes of decision making. Transformative politics of resistance therefore is constituted at this very juncture of erasure where voices of local communities from the global margins are continually being erased to push down monolithic logics of neoliberalism: In such instances, how then do communities from the margins create opportunities for participation?

Throughout this book, working through several case studies, we will actually listen to the voices of the men and women who have been violently rendered invisible in dominant structures of policy making and program planning under neoliberal hegemony. In weaving together the stories of resistance in the pages of this book, I will emphasize the processes of co-construction that lie at the heart of the culture-centered approach; the erasure of communities from the global South is resisted through the presence of those voices of change within the discursive spaces of knowledge production, representation, and circulation. Each of the examples that are woven into this book offer insights into the dignity and resilience with which communities at the margins seek to challenge structures of invisibility so that their voices may be heard; these struggles about economic justice, agricultural justice, environmental justice, political justice are each also struggles for voice. Through their voices, we listen to the stories of resistance through which local communities collaborate with other local communities dispersed across the globe to work toward fostering platforms where their voices would shape the realms of theorizing and praxis. We will begin this chapter by introducing the concept of resistance in the communication literature and by foregrounding the contributions of the culture-centered approach to this literature on resistance. We will then examine the foundational framework of globalization and attend to the basic premises of neoliberalism that constitute the political economy of globalization. Our deconstruction of neoliberalism will set the stage for understanding the paradoxes and hypocrisies that are embodied in conceptualizations of neoliberalism; it is through this journey of deconstruction that we will then outline some of the key themes that guide the culture-centered approach to social change communication.

Resistance and Communication

Communication scholars studying resistance emphasize the discursive elements of resistance, noting that resistance is constituted, constructed, negotiated, and enacted through discourse (Mumby, 2005; Pal & Dutta, 2008). Communication constitutes the framework for resistance through discourse, offering the template of meanings on which resistive acts are formulated (Dutta, 2009). Communicative approaches to resistance study the notion of everyday forms of resistance, understanding resistance in terms of the subjectivities of individuals negotiating structures (Alvesson & Deetz, 2000; Mumby, 1997), along with resistance studies that emphasize collective processes of organizing, and more recent emphases on understanding resistance in subaltern and postcolonial contexts (Broadfoot & Munshi, 2007; Dutta, 2008, 2009, 2011; Munshi & Kurian, 2007). The thread that runs through these various studies of resistance is the focus on the role of communication in constituting, reproducing, and enabling resistance in a wide variety of contexts (Dutta, 2009, 2011; Zoller, 2005). It is through communication that individuals and communities come to develop their resistive identities, and form the frameworks for resistive action (Dutta, 2011). Communication, in other words, creates the thread that weaves acts of resistance in relationship to the dominant structures of oppression, offering entry points for disrupting and/or transforming these structures. Communicative performances such as songs, speeches, slogans, poetry, and dances emerge as avenues for reshaping the contours of power by opening up new meanings and by recrafting existing meanings (Carawan & Carawan, 1963; Cohen-Cruz & Schutzman, 2006; Conquergood, 1986; Denzin, 2003; Deshpande, 2007; Foster, 1996; Gomez-Pena, 1993, 1996, 2000; Hashmi, 2007; Martin, 1998). These performative forms often emerge in communicative modes that challenge the essential rationalities of communication within dominant structures (Dutta, 2011). The messages that are constituted in these communicative acts, on the one hand, resist the very rationalities of communication that make up the expectations of dominant structures; on the other hand, they emerge in forms that disrupt the assumptions that underlie the perpetuation of resistance.

The emancipatory or the critical thrust in research on resistance, informed by Marxist theories, focuses on workers’ interests and explores possibilities of worker revolution, drawing upon the role of discourses in mobilizing collective forms of resistance (Cheney & Cloud, 2006; Dutta, 2010; Pal & Dutta, 2008a, 2008b). Communication here is seen as the basis for the formation of identities, for the sharing of frames that comprise the basis for collective organizing, and for the development of the ambits of collective action (Dutta, 2009, 2011). In other critical work, the focus is on bringing about structural transformations through grassroots participation in processes of change; once again, communication forms the foundation of the grassroots processes of organizing (Dutta, 2011; Dutta-Bergman, 2004a, 2004b; Frey & Carragee, 2007; Zoller & Ganesh, 2012). Participatory processes of communication in local communities bring communities together in solidarity, set in opposition to oppressive structural forces. Through conversations, dialogues, and sharing of information and resources, these localized communities offer resistance to broader structures (Dutta, 2011). Resistance is fundamental to the processes of change in such localized grassroots movements, written in direct opposition to the structures of oppression. For the most part, this idea of resistance embodies the mobilization of a collective identity that opposes the exploitative goals of dominant social actors that control the sites of production. In the context of class-based acts of resistance, estranged from the ownership of production, laborers must abolish private ownership of production by organizing “class-based resistance” (Jermier, Knights, & Nord, 1994, p. 3). Members exert control through economically sustained access to discursive spaces and processes that serve as sites of power and control; resistance, therefore, is constituted in opposition to the materially located economic disparities within the system (Cloud, 1994; Marx, 1867 /1967). In this sense, in Marxist processes of organizing, the communication among workers, the formation of organized identities, and the fostering of collective demands through meetings and discussions become the bases for economic organizing. The development of material strategies of resistance is built upon communicative processes (Dutta, 2011). The resistive consciousness is formed and expressed through participation in processes of communication. The relationship between material and discursive practices fosters possibilities of structural transformations (Artz, 2006; Cheney & Cloud, 2006; Pal & Dutta, 2008a, 2008b). When workers develop strategies such as going on a strike, they do so through communication. Furthermore, the strategy of going on a strike is at once material and communicative; it holds its economic power to disrupt by communicating its resistive message to the dominant structure. Organizing here fosters a space for resistance. Furthermore, in the context of subalternity, resistance in and of itself becomes a struggle for spaces of recognition and representation (Dutta, 2011). The challenge to structures are constituted amid the organized struggles of subaltern communities to seek out representation and recognition within those discursive spaces and processes in the mainstream that have effectively erased them and carried out their economic marginalization through these processes of erasure. In this sense, transforming the very nature of the communicative processes and spaces lies at the heart of resistance; it is through communication at the mainstream sites that subaltern communities disrupt the logics of oppression.

Within Communication Studies,, with the growing relevance of post-modern criticisms that drew attention to the ambiguities and fluidity in the relationship between control and resistance, scholarly attention shifted to studying the micropractices of resistance within a critical postmodern framework (Mumby, 2005; Tretheway, 1997, 2000). In this sense, the literature on micropractices was directed toward disrupting the metanarratives of modernist frameworks in resistance research. Contrary to totalizing collective consciousness of resistance in the realm...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter One Introduction: Voices of Resistance

- Chapter Two Resisting Global Economic Policies

- Chapter Three Agriculture: Voices of Resistance

- Chapter Four Resistance, Social Change, and the Environment

- Chapter Five Social Change and Politics

- Chapter Six Resistance, Development, and Social Change

- Chapter Seven Epilogue: Voices in Motion

- References

- Index