![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Need for Different

Ways of Handling

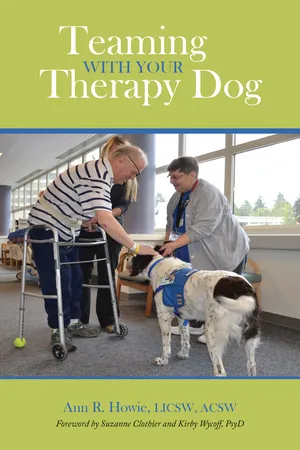

Josie thinks her German Shepherd, Logan, could be a therapy dog. They have competed successfully in obedience, and Logan has earned three obedience titles. Josie is looking for something different to do with Logan, and she’s taken him to a therapy dog evaluation. The evaluation is in a nursing home, where residents watch through a wall of windows.

Some of the test exercises are quite similar to exercises they did in obedience, where Logan walks by her side, sits, lies down, stays in place, and comes to Josie when she calls him from a distance. During this evaluation, Josie focuses on Logan, watching him more than she watches the evaluator, even though she is paying close attention to the evaluator’s instructions.

During the walking exercise, she varies her pace slightly to accommodate Logan. She talks to him in a conversational tone of voice, making comments that help observers see their teamwork. For example, when Logan slows to sniff something on the ground, Josie also slows and says, “Is that a really good smell, Logan? I’m sure there are many good smells here. Well, we need to keep going now. We have people waiting to see us!” This helps him refocus on Josie, and they continue their walk in harmony.

When the evaluator asks her to show how Logan sits on cue, Josie looks gently into Logan’s eyes and whispers, “Sit,” so softly that the evaluator barely hears her. Logan sits immediately, and Josie reaches over and scratches him in his most loved place, telling Logan how brilliant he is. Similarly, when asked to demonstrate Logan’s response to her down cue, she looks adoringly into his eyes and makes a small movement with her hand. Logan immediately lies down. Josie tells him he’s the best dog in the world and pets him with long, slow strokes (Logan’s favorite). Her heart swells with pride at how Logan is doing, even though she’s feeling nervous about the test.

The residents watching are impressed and smile at each other as they comment, “Such a calm, obedient dog!” “What a gentle handler!” “They work so well together!”

Josie used teamwork principles with Logan during these exercises, and their success as a team caused everyone to smile and feel comfortable with them. Imagine how that might have gone differently if, in Josie’s nervousness, she reverted to obedience mode by walking briskly instead of varying her pace, looking straight ahead instead of watching Logan, speaking brusquely instead of conversationally, and giving a broad hand signal instead of a subtle one. The tone of that evaluation would be much different. In fact, the residents might have assumed that since Logan was a police dog, he might require such firm handling, which could estrange her and Logan from the residents.

To be effective in animal-assisted interactions (AAI), our handling skills must fit with the environment and engage the clients we are visiting. Yet few of us inherently know what that looks like or how to accomplish that without obtaining some coaching. Here are two examples.

Imagine a therapist working with a therapy dog to counsel a woman who has been injured as a result of domestic violence. This client will be sensitive to the slightest hints of coercion in relationships. Upon entering the therapist’s office, the client finds the dog on the couch. Imagine the client’s response if the therapist first asks the client respectfully if she wants the dog off the couch, then (after an affirmative reply) asks the dog conversationally to please move off the couch and gives a subtle hand signal to the dog, pointing casually to the dog’s bed.

In contrast, how different the client’s perception could be if she sees the therapist pull or shove the dog off the couch to allow the client to sit there. Or if the therapist tells her dog in a loud, no-nonsense tone to “get down!” A client who senses harshness in the therapist’s relationship with her dog has little reason to feel that she will be respected by the therapist. A handler who teams respectfully and collaboratively with her therapy dog increases the value of her interactions with clients.

Your dog trusts you to take care of him.

Even more important than improving your relationship with clients, teaming with your dog enhances your relationship with your dog. Teaming with your dog helps you be a companion to him. Think about this: What do you see in your dog’s eyes as he looks into yours? Some people call it love, and perhaps it is. I interpret it as trust. Your dog trusts you to take care of him.

To me, taking care of my dog means more than providing food, water, and shelter. It also means avoiding placing him in situations where he might be harmed. I refuse to knowingly inflict harm on anyone. I want to continue to earn my dog’s trust. By teaming with him during visits, I show him continually that he can trust me.

To effectively team with our therapy dogs, we must be aware of our actions and how they affect those around us. Then we must act consciously with our dogs rather than unconsciously.

Conscious awareness leads to conscious actions

In most areas of life it is possible for us to feel one way and act another. We can love our spouse /partner and still snap at him or her in irritation. We can know that our bank balance is low, yet still use a credit card for an impulse purchase. We can want to lose weight, yet still keep a supply of our favorite candy in the cupboard.

This applies in our relationships with our dogs, too. We can love them, yet act conversely by talking to them with a harsh tone of voice, pushing them into a desired position, or jerking on their necks as they pull on the leash. We can act in a manner that creates emotional distance between us, yet believe we have a mutually close relationship. (Remember in the introduction when my trainer asked me to pretend that I liked my dog Troi?)

I’m not suggesting we permissively let our dogs misbehave. On the contrary! I much prefer to be around well-behaved dogs. And well-behaved people, too. What I’m asking is that we consider how we help our dogs be well-mannered. The manner in which we interact with our dogs is a significant part of teamwork. We can be polite and firm with our dogs just like we can be polite and firm with our family, friends, and colleagues. (And sometimes we can be permissive.)

Ask yourself this: Is your relationship with your dog mutually beneficial? In other words, does your dog get as much from your relationship as you do? I wish you could ask your dog this question and compare your answers!

A Mother Goose and Grimm comic by Mike Peters gives us a glimpse into how some dogs might feel about their relationship with their handler. In this strip Mother Goose is sitting on a park bench talking with a friend, and her dog, Grimm, is on a leash by her side. Mother Goose waxes eloquent about how wonderful her relationship with Grimm is — how it is a bond that will last for life. In the last panel, Grimm’s opinion contrasts with that of Mother Goose as he emphasizes that what she calls a bond, he calls a leash.

I hope our dogs feel that there is more to our relationships with them than just a leash! We express relationship through tone of voice, the characteristics of our touch, the kinds of words we use, the quality of our eye contact, and the expressions on our face. My goal with my dogs is to maintain a relationship that keep us close physically and emotionally irrespective of a leash, both at home and during AAI.

Angie Mienk is a professional dog trainer in the United States and in Germany. In her book, The Invisible Link to Your Dog, she offers ideas that are compatible with teamwork principles. This includes a breakdown on the role of the leash:

| A leash does | A leash does not |

| • Support the dog | • Hold the dog |

| • Give the dog security | • Secure the dog |

| • Protect the dog | • Protect someone from |

| • Give the dog liberties | the dog |

| • Provide a loose connection | • Limit the dog’s liberty |

| between handler and dog | • Tie the dog down |

As therapy dog handlers, we need to take a look at how we use a leash with our dogs. Are we like Mother Goose in the comic, thinking that Spike is closely connected to us emotionally, when he thinks the leash is tying him down? Do we support Spike through the leash or contain him?

Teaming with our dogs leads us to work together as extensions of each other. Teamwork doesn’t mean you have a relationship where everything always goes your way. In a healthy partnership, both members respect each other. They have a give-and-take relationship with ups and downs. They both feel comfortable and secure in their relationship. They know when to follow and when to lead. (Yes, therapy dogs can have opinions about which client to see when, and handlers who truly team with their therapy dog know when to let their dog lead.) Good teamwork is beautiful to behold. It is like watching a figure skating pair dance on ice. Seamless. Intuitive. Respectful. Spiritual.

To paraphrase a well-known saying, “To the world, you’re just another dog owner. To your dog, you’re the only owner in the world.”

A joyful, respectful relationship is my goal with my dogs. Since you’re reading this book, I believe you’re open to exploring how you as a handler can interact with your dog to honor his worth and value him as an individual and as a therapeutic agent. When we respect our dogs, our relationships with them are much more likely to be mutually beneficial.

How we handle our dogs is directly related to the way we train our dogs. Is the training method you use teamwork friendly? Or is it designed to place you in charge so that you may force your will upon your dog?

When I was learning about dog training, the only method available was based on punishment: If the dog didn’t do what I wanted him to do, I was to punish the errant behavior out of him. Today there are almost as many different methods of dog training available as there are dog trainers.

“To the world, you’re just another dog owner. To your dog, you’re the only owner in the world.”

— Anonymous

There are still trainers who make their living advocating punishment-based training methods. However, think about what you want as an end result. Do you simply want a dog who does what you tell him to do? Or do you want a partner in your life and work? Do you want to be a companion to your dog? Or do you only want your dog to be a companion to you? The training method you choose will affect the end result.

A dog who is accustomed to being punished for independent thought waits to be told what to do. Some people like that in a dog. On the other hand, I suggest that a handler who hopes to train a therapy dog wants to nurture a dog who can think for himself and make independent decisions while relying on his handler for guidance and support. That kind of dog does not develop in response to punishment. As a result, I encourage therapy dog handlers to adopt a training philosophy that relies on rewarding desired behaviors rather than punishing unwanted behaviors.

It is common for people to want their dogs to stop doing something. Stop chewing shoes. Stop digging holes in the yard. Stop chasing the cat. Most of us pay attention to disruptive behaviors: barking, pawing at us, running around or away, jumping up on us, whining, and so forth. And often people can be found yelling in frustration to get the dogs to stop those behaviors. It is harder for most human beings to notice the good things — especially if someone thinks he is “owed” those good behaviors.

We rarely think about rewarding the good behaviors so that there is a higher likelihood of those behaviors being repeated. It is easier to think about punishing something that is wrong than rewarding something that is right. The dog who stops pawing at us is easy to ignore in relief, as we think, “Finally, he stopped!” Yet look at it from Rover’s perspective: He got more attention from pawing than from being quiet. So which behavior do you think Rover is more likely to repeat? We rarely notice when our dogs are being quiet, because their quietness allows us to remain engrossed in our television program or computer game. When we are interrupted from doing what we want to do, however, we notice!

Our culture has not trained us to notice the good stuff. How rare is it for your boss to praise you for things you’re doing right instead of listing the problems you need to correct? Rather than reinforcing the good, as a culture we focus on changing the bad. Yet we can often change the bad by reinforcing the good. More good means less bad. It is certainly possible to get more good behaviors by reinforcing behaviors we like, whether in people or in dogs.

There is a Baby Blues comic strip by Jerry Scott and Rick Kirkman that provides a delightful illustration of this principle. The comic shows an older sister coaching her baby brother in how to color. The more he enjoys himself, the more he colors outside the lines, to which she responds with anxious yelling. When their mother intervenes, the sister says, “If I don’t yell at him, how is he going to know when he’s messing up?”

We can have the same goal in our relationships with our therapy dog partners as we do with our human partners: to trust each other and work together. Yet we know that this goal is not easy to achieve — especially if our communications focus on pointing out things we don’t like.

Would you be surprised to learn that there is a therapist who can accurately predict whether a couple will divorce or reconcile after a simple interview? John M. Gottman, PhD, is well-known and highly respected internationally in the field of couples counseling. He founded the Gottman Institute in Seattle, Washington, where he provides training for therapists and counseling for couples. He is considered to have revolutionized the study of marriage.

Dr. Gottman describes the seemingly miraculous accuracy of his prediction by explaining that couples who will stay together have a 5:1 ratio of positive things (comments, behaviors) to negative things in their interactions — even during conflict. He suggests that negative things have far greater impact on us emotionally than do positive things. This sounds like common sense to anyone who has been chastised and remembers what that felt like. Consequently, it takes five times more positive things to “make up for” one negative thing.

Now apply that to your interactions with your dog. What is yo...