eBook - ePub

Successfully Implementing Problem-Based Learning in Classrooms

Research in K-12 and Teacher Education

- 300 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Successfully Implementing Problem-Based Learning in Classrooms

Research in K-12 and Teacher Education

About this book

Problem-based learning (PBL) represents a widely recommended best practice that facilitates both student engagement with challenging content and students' ability to utilize that content in a more flexible manner to support problem-solving. This edited volume includes research that focuses on examples of successful models and strategies for facilitating preservice and practicing teachers in implementing PBL practices in their current and future classrooms in a variety of K-12 settings and in content areas ranging from the humanities to the STEM disciplines. This collection grew out of a special issue of the Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning. It includes additional research and models of successful PBL implementation in K-12 teacher education and classroom settings.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Successfully Implementing Problem-Based Learning in Classrooms by Thomas Brush,John W. Saye in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education Theory & Practice. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education Theory & PracticePART I

PROBLEM-BASED LEARNING

IN TEACHER EDUCATION

1

TRANSFORMING PRESERVICE

SECONDARY MATHEMATICS TEACHERS’

PRACTICES: PROMOTING PROBLEM

SOLVING AND SENSE MAKING

Marilyn E. Strutchens and W. Gary Martin

Introduction

Since the 1970s, there have been calls for changes in mathematics instruction emphasizing problem solving, culminating with the recommendation by the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM) in 1980 that “problem solving be the focus of school mathematics” (p. 1). Throughout the 1980s, there was considerable research on how to promote students’ problem solving in mathematics (cf. Charles & Lester, 1984; Goldin & McClintock, 1984; Schoenfeld, 1985). Near the end of the decade, a distinction was drawn between a focus on problem solving as an end of instruction (i.e., “teaching about problem solving”) and a focus on problem solving as a means of instruction (i.e., “teaching via problem solving”) (Schroeder & Lester, 1989, p. 32). This process view of problem solving promotes students’ development of a relational understanding of mathematics (Skemp, 1976/2006) in which students understand both mathematical procedures and the reasoning behind those procedures.

In the NCTM’s first set of national standards, both perspectives were valued; the first standard for each of its three grade bands was “Mathematics as Problem Solving,” which called for students to “use problem-solving approaches to investigate and understand mathematics content” as well as “to develop and apply strategies to solve a wide variety of problems” (1989, p. 23). The subsequent Professional Standards for Teaching Mathematics (NCTM, 1991) described ways of supporting students’ development of problem solving through the use of worthwhile tasks, classroom discourse, and an effective learning environment. This primary focus on problem solving in mathematics education was maintained through multiple “NCTM standards” documents produced over the following two decades (NCTM, 1995, 2000, 2006, 2009). As stated in Focus in High School Mathematics: “In the three decades since the 1980 publication of An Agenda for Action, NCTM has consistently advocated a coherent prekindergarten through grade 12 mathematics curriculum focused on mathematical problem solving” (NCTM, 2009, p. xi). Focus in High School Mathematics further framed problem solving in terms of “reasoning and sense making”—that is, reasoning is “the process of drawing conclusions on the basis of evidence or stated assumptions,” while sense making requires “developing understanding of a situation, context, or concept by connecting it with existing knowledge” (p. 4).

In 2010, the National Governor’s Association (NGA) and the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO) developed the Common Core State Standards for Mathematics, which more than 43 states and territories adopted as their state course of study. In addition to promoting a more “coherent and focused” mathematics curriculum (p. 3), the document includes a required emphasis on problem solving and mathematical sense making in the Standards for Mathematical Practice, process and proficiencies that students should develop across the grades. These practice standards require that students develop the ability to make sense of problems and persevere in solving them, reason abstractly and quantitatively, construct viable arguments and critique the reasoning of others, model with mathematics, use appropriate tools strategically, attend to precision, look for and make use of structure, and look for and express regularity in repeated reasoning (NGA & CCSSO, 2010).

While the Common Core set both content and practice standards for K–12 mathematics, the document did not provide guidance for how schools and teachers might support students in achieving those standards. In response, the NCTM released Principles to Actions: Ensuring Mathematical Success for All in 2014. This document describes “essential elements” of school mathematics programs that will support student attainment of the Common Core, along with research-informed “mathematical teaching practices” to support students’ mathematical learning, which is explicitly described to include problem solving and sense making. This latest standards-genre document from the NCTM is quickly gaining support as a primary source in framing discussions around mathematical teaching and learning.

In this chapter, we discuss how we work to transform the mathematical teaching practices of preservice secondary mathematics teachers to develop an equitable, inquiry-based approach to teaching in a manner that will help them to create classroom environments that foster mathematical problem solving and sense making. We discuss a range of pedagogical strategies and describe how these strategies might be introduced in methods courses and reinforced during teacher candidates’ clinical experiences, including early field experiences and student teaching.

Instructional Practices to Promote Problem Solving and Sense Making

In this section, we describe research-based instructional practices that promote problem solving and sense making. These are the targets for our preparation of secondary mathematics teachers. We begin by describing tenets related to teaching and learning mathematics, consider the importance of the classroom environment, and, finally, discuss specific mathematics teaching practices described by the NCTM in 2014 to promote students’ mathematics learning of problem solving and sense making.

Foundational Tenets for Teaching and Learning Mathematics

As teacher candidates begin to conceptualize how to teach mathematics in a meaningful way, they need to understand some tenets that should undergird their development of lesson plans and how they enact those lessons with students.

Relational versus instrumental understanding. Skemp (1976/2006) defined relational understanding as “knowing what to do and why” and instrumental understanding “as rules without reasons” (p. 89). Preservice secondary mathematics teachers need to know the difference between the two kinds of understanding because most preservice secondary mathematics teachers have largely experienced learning mathematics in an instrumental way. Realizing the differences between the two types of understanding, experiencing learning mathematics in a relational manner, and seeing the results of students developing relational understanding of concepts are important experiences for secondary mathematics preservice teachers.

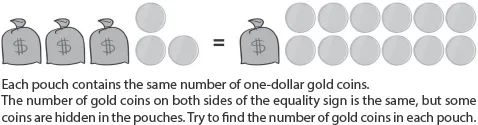

Placing preservice secondary mathematics teachers in situations in which they develop a relational understanding of a concept helps them to see the difference between relational understanding and instrumental understanding. For example, allowing preservice secondary mathematics teachers to work with mystery pouches and coins can help them understand how to solve equations in a meaningful way. Preservice teachers are given a picture such as the one in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Task promoting meaningful use of equations. (From Moving Straight Ahead: Linear Relationships by G. Lappan, J. T. Fey, W. M. Fitzgerald, & S. N. Friel, 2014, Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Reprinted with permission.)

The pouches in the figure are related to the variables in an equation, and the coins represent the constants. The equation represented by the picture is 3x + 3 = 2x + 12. In thinking about the picture, the students know that each of the pouches contains the same number of coins. In balancing the equation, they know that the two pouches on each side are equal and three of the coins on the right side are the same number as three of the coins on the left side. They then know that each pouch has to contain nine coins in order for the equation to be true because they are left with one unmatched pouch on the left side of the equation. These problem types enable preservice teachers to understand that variables represent unknown quantities, which will make the equation true.

In addition to asking preservice teachers to solve these types of problems, they are asked to reflect on their thinking and to think about how helping students to develop a relational understanding of concepts and skills such as this will enable them to reason and make sense of mathematics. In addition, showing preservice teachers videos of students solving problems and presenting their solutions in a relational manner helps to confirm why it is important to teach mathematics in a relational manner.

Furthermore, Pesek and Kirshner (2000) posited that in order “to balance their professional obligation to teach for understanding against administrators’ push for higher standardized test scores, mathematics teachers sometimes adopt a two-track strategy: teach part of the time for meaning (relational learning) and part of the time for recall and procedural-skill development (instrumental learning)” (p. 524). Moreover, they specifically addressed the problems that might occur when rote-skill development (instrumental understanding) occurs prior to teaching for relational understanding. In addition, they found that students who were taught area and perimeter via instrumental instruction before they received relational instruction “achieved no more, and most probably less, conceptual understanding than students exposed only to the relational unit” (pp. 537–538). Pesek and Kirshner also found that students who learned area and perimeter as a set of how-to rules referred to formulas, operations, and fixed procedures to solve problems, whereas students whose initial experiences were relational used conceptual and flexible methods to develop solutions. Finally, the authors shared that extensive time spent on routine exercises to consolidate rote or procedural knowledge does not lead to the kind of learning that takes place through the time given to students’ intuitive and sense-making capabilities.

Equity. Another tenet of inquiry-based teaching is equity. Understanding that all students need the opportunity to reach their full mathematics potential is crucial for secondary mathematics preservice teachers. Preservice secondary mathematics teachers need to understand what it means to achieve equity in a mathematics classroom, examine barriers related to student engagement and achievement, develop equitable pedagogical strategies, and examine their beliefs about students from different race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, gender, ability, and sociolinguistics groups, and confront the negative beliefs (NCTM, 2014; Strutchens, 2000).

Preservice teachers need to think about the meaning of equity from different perspectives. They should understand that “equity does not mean that every student should receive identical instruction; instead, it demands that reasonable and appropriate accommodations be made as needed to promote access and attainment for all students” (NCTM, 2000, p. 12). Equity also means “being unable to predict students’ mathematics achievement and participation based solely upon characteristics such as race, class, ethnicity, sex, beliefs, and proficiency in the dominant language” (Gutiérrez, 2007, p. 41). Teachers should also think of equity as a bidirectional exchange—which is different from equity as primarily benefitting growth of students and student groups that have historically been denied equal access, opportunity, and outcomes in mathematics to a reciprocal approach where teachers are learning from the students and what they bring from their cultural backgrounds (Civil, 2007). In addition, the concept of equity includes “the equitable distribution of material and human resources, intellectually challenging curricula, educational experiences that build on students’ cultures, languages, home experiences, and identities; and pedagogies that prepare students to engage in critical thought and democratic participation in society” (Lipman, 2004, p. 3). In addition, according to a joint position statement of the National Council of Supervisors of Mathematics and TODOS: Mathematics for All (2016), “a social justice stance requires a systemic approach that includes fair and equitable teaching practices, high expectations for all students, access to rich, rigorous, and relevant mathematics, and strong family/community relationships to promote positive mathematics learning and achievement. Equally important, a social justice stance interrogates and challenges the roles power, privilege, and oppression play in the current unjust system of mathematics education—and in society as a whole” (p. 1).

These conceptions of equity are made concrete to preservice teachers when they actually experience equitable pedagogy as students in their methods classes, and then practice implementing equitable pedagogy in their field experiences. According to Banks and Banks (1995), equitable pedagogy focuses on the “identification and use of effective instructional techniques and methods as well as the context in which they are used,” “challenges teachers to use teaching strategies that facilitate the learning process,” and “provides a basis for addressing critical aspects of schooling and for transforming curricula and schools” (p. 153). Teachers may use mathematics autobiographies and other means to get to know their students and foster positive mathematics identities in students. Teachers may ask students to engage in social justice activities, such as studying statistics related to racial profiling and determining whether injustices have occurred, and then suggesting what steps should be taken next (Gutstein, 2003). Teachers may ask students to develop and explore m...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Problem-Based Learning in K–12 and Teacher Education: Introduction and Current Trends

- Part I: Problem-Based Learning in Teacher Education

- Part II: Problem-Based Learning in K–12 Contexts

- Conclusion: What Is Missing; What Is Needed? Future Research Directions With PBL in K–12 and Teacher Education

- Index