| 1 | What do you really think about customers? |

Introduction

A midweek morning in the spring of 1989, in an otherwise empty chic London Italian restaurant, four men and a woman, all in their late twenties or early thirties, sit around a table drinking strong coffee from frequently replenished cafetiÈres placed on the crisp white tablecloth. They talk animatedly, good-humoredly, with intensity. The subject? What their company, an advertising agency, stands for. Why, five years previously, they had broken away from other agencies to found it. What has made it successful and what makes it different, special.

Looking on, a man listens intently to the conversation and, every so often, probes to find out more about a particular aspect of the discussion, or shifts the conversation in a new direction. Around the table two cameramen move unobtrusively, capturing the shifting dynamics of the conversation on film. A sound recordist optimizes the sound pickup through carefully positioned microphones.

What’s going on here is a result of the advertising agency commissioning a film to showcase some of its work and give prospective clients an insight into the company’s philosophy. The head of the film production company – the guy listening and asking questions – recognized that a key part of the advertising agency’s offering is its passion for what it does; which is why he proposed this roundtable, free-flowing approach to getting the principals’ thoughts and ideas on film. The final output – a seven-minute, tightly edited, fast-paced film with high production values – will succeed in getting across the energy, the passion, the excitement of their organization.

Now fast forward 20 years to 2009. Our corporate film producer is still in business but the world has changed. In the nascent internet, minimally broadband-enabled world of the late 1980s, corporate video was a must-have part of the marketing mix, backed by good budgets. Twenty years later, technological advances have put video within easy – and easily distributable – reach of many more users. Rather in the way that Microsoft PowerPoint has empowered everyone to become a presentation expert (or so they think!), new video technologies have enabled just about anyone to make videos.

In face of this, our film producer finds life more difficult. The budgets required to make the kinds of films he used to make are hard to come by. Too frequently, prospective clients say: ‘How much? You must be joking! We can make a film for a fraction of that!’ And, of course, they’re right.

So what is our film producer to do? A clue comes from a client testimonial that the film producer has. A senior executive in a global company said: ‘[His] films have been part of helping transform the way we communicate our marketing objectives internally… The films are not inexpensive but the creative result means our people watch them. [He] delivers great value and I would recommend him unreservedly.’

What is actually happening here, as you may have gathered, is that the most valued thing about our film producer is not that he makes films. The greatest value comes from his ability to facilitate the analysis of situations to get absolute clarity, so that messages can be brilliantly communicated. And, in today’s business world, that’s a skill worth its weight in gold.

Think about it: this insight brings profound implications for the way our film producer conducts his business. For instance, it implies that his competitors (the clients’ alternative sources of supply) are not – or not just – other film production companies. It means, too, that for as long as our film producer continues to lead his business on the basis of its being a ‘corporate film production company’, prospects will assess it on that basis and may try to drive down prices to a commoditized, lowest common denominator. If all a prospect’s procurement experts are worrying about is the relative cost of a cameraman, or a sound recordist, or the hourly rate in an edit suite, they will have completely missed the point… and our chap will have lost the business.

The important factor is the client experience. What issues does the film production company address or solve for a client? Why do those issues occur, and what underpins them? And what other companies (markets, segments, specific companies) experience those issues and would, therefore, represent good sales opportunities?

These are the issues this book sets out to illuminate. We are talking about value propositions. And let’s make it clear from the outset that a value proposition is not what you do. It is the value experience that you deliver. In the example just given – which is factual but disguised – our film maker’s Value Proposition is not that he makes good films!

The films that he makes may be wonderful but the value delivered is something else, and something that is hugely more valuable.

What do you really think about customers?

The events most critical to a business happen outside the firm managing it. These are the events that the customer experiences as a result of using and interacting with the firm’s products, services, and actions. Yet these resulting experiences and their implications often escape the real attention of managers in conceiving and executing business strategy.

(Delivering Profitable Value, Michael J. Lanning, Perseus Publishing, 1998)

This book is about value propositions (VPs): what they are (and what they are not); their importance in the successful running of a 21st-century business; how to create them; and how to apply them. To be clear, we have used the terms ‘client’ and ‘customer’ interchangeably throughout this book.

What is important to understand is that there may well be, of course, more than one customer in the chain. For example, a hardware manufacturer may sell through resellers who, in their turn, sell to end users. Identifying the customer chain is important because value propositions depend on your being able to analyse, quantify and articulate the experience that a customer will receive when choosing your offering.

So, before we get into the value story, it’s useful to take a step back to consider attitudes towards clients and their customers. Why? Because the way we think about clients and their customers is a key influencer of the way we think about business in general, and marketing and selling in particular. This is important because value propositions can only function within what we term a value-focused enterprise, and value focus is a function of the way clients and customers are viewed and treated.

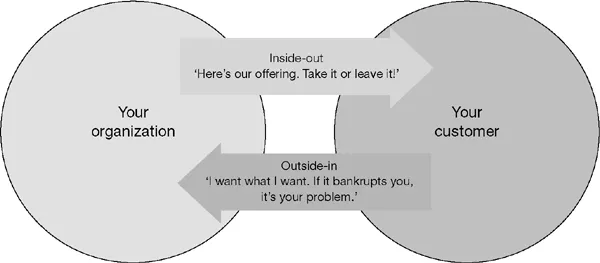

So what is your client mindset? Often, our attitudes towards client–supplier relationships are deeply ingrained and go to one or other of two extremes:

- Inside-out: ‘Clients must be persuaded to buy what our organization decides they should buy, based on ease and convenience for our organization.’

- Outside-in: ‘Clients must be supplied with whatever goods or services they say they want.’

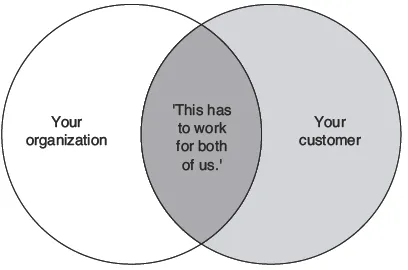

In today’s marketplaces, both of these approaches risks driving a business into bankruptcy. A value-focused approach using VPs is different because it requires you to put yourself in your customer’s shoes… and before you can put on someone else’s shoes, you have to take off your own.

Both the inside-out and outside-in models are confrontational, based on the fact that one party must win and one must lose: see Figure 1.1. The value-focused model is different: see Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.1The inside-out and outside-in models

Figure 1.2The value-focused approach

Before exploring the value-focused approach in more detail, let’s explore the fundamental idea of a ‘customer’.

The lessons of childhood

Because we have all engaged in transactions from an early age, our attitudes and beliefs about buying and selling are often ingrained to the point of fossilization. When you were a child you probably played at ‘shopping’, pretending to be either the customer or the storekeeper, handing over pretend money in return for pretend commodities. Then, very early on, that business simulation translated itself seamlessly into reality when you handed over real money in return for real comic books and the other essentials of early life. So, by the time you reached maturity, the business of buying things was second nature, and the notion of being a customer was so innate as to be completely internalized and unconsidered.

That’s the problem. It means that when any of us uses the word ‘customer’ its meaning and implications are taken for granted. We assume that everyone has a shared, common definition of ‘customer’ – not only in the literal sense of ‘an acquirer of a good or service’, but also in the underlying behavioural and emotional components t...