eBook - ePub

The Neanderthals Rediscovered

How Modern Science is Rewriting Their Story

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Neanderthals Rediscovered

How Modern Science is Rewriting Their Story

About this book

For too long the Neanderthals have been seen as evolutionary dead-ends but advances in DNA technologies have forced a reassessment of their place in our own past. This extensively illustrated book looks at the Neanderthals from their evolution in Europe to their expansion to Siberia and their subsequent extinction. It turns out that the Neanderthals' behaviour was surprisingly modern so what caused their extinction? This is one of many mysteries that we are closer to solving. They evolved in Europe in parallel to the Homo Sapiens line evolving in Africa. When both species made their first moves into Asia, the Neanderthals may even have had the upper hand. The superiority of Homo sapiens suddenly seems less obvious or inevitable.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Neanderthals Rediscovered by Dimitra Papagianni,Michael A. Morse in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER one

A Long Underestimated Type of Human

From our perspective as Homo sapiens, it can be tempting to look back on human evolution with a sense of triumph and destiny. With our large brains, crafty hands, agile legs and complex social networks, it was surely inevitable that when the conditions became favourable, we would assume our rightful place at the very pinnacle of nature. But perhaps it is a little too easy to claim this now that we have no serious rivals, and certainly no human ones.

We are only one variety, ‘modern humans’, of up to a dozen human species that have shared our world in the last two million years or so. And our direct ancestors were not always in the leading position. If we could rewind the clock to the last time the world was as warm and stable as it is today – some 120,000 mostly icy and climatically erratic years ago – we would probably not feel as privileged as we do now. Back then, the Neanderthals – a species much like us, only stronger – were on the march. With unprecedented abilities to survive cold climates, this rival species might have been the prime candidate to populate the whole Earth from its origin point in Europe and push other forms of human to extinction. Over some tens of thousands of years from that point, the weather deteriorated, and enormous ice sheets advanced in the northern latitudes. Somehow, the particular human species native to Europe managed to survive these hardships, while our ancestors faced warmer challenges in Africa and, later, tropical Asia.

Fast-forward to about 45,000 years ago, when modern humans first ventured into a Europe half-covered by glaciers. There they encountered a form of human that, unlike themselves, had already lived through several cold episodes. Yet it was the warm-adapted Homo sapiens that survived this most recent glacial cycle. The cold-adapted Neanderthals failed, dying out in the millennia after our ancestors arrived in their homeland.

The species equivalent of our first cousins, the Neanderthals were unmistakably different from modern humans, with large, barrel-shaped chests, stocky and muscular bodies, broad noses and chins that did not protrude. They shared many of our behaviours, but their development seemed to trail ours in some key areas, such as our capacity for symbolic expression.

Even their world was alien to ours. The open, steppe-like landscapes that prevailed in Europe in their heyday enjoyed good exposure to sunlight and had rich vegetation that sustained sizeable populations of mammoth, bison, deer and horse – species essential to the Neanderthal diet. Neanderthal landscapes were unlike the barren steppes of present-day Eurasia or, indeed, any landscapes anywhere in today’s world.

The Neanderthals are the only native European species in the human family tree, and this alone has fostered an enduring fascination with them. Europe has a much longer history of archaeological investigation and research, and therefore a richer record of its distant past, than any other part of the world. We have known them longer – since we discovered them in the 19th century – than any other extinct form of human.

And because the Neanderthals are a relatively recent species, their fossilized bones, the remains of their everyday lives and even their DNA are well preserved. The Neanderthals are not just one of our closest relatives. They are also the ones we know best. With Neanderthals, we are as close as we will ever get to another species from the human evolutionary past.

Like so many people who are different from us, the Neanderthals are now known mainly for the use of their name as a pejorative. In this book, we do not pretend to be able to correct this popular usage, but we do hope to restore some dignity to those we replaced.

The Neanderthals have always been a little too close for comfort for the modern western world. Their name conjures up images of muscular but dim-witted cavemen who relied on force over cunning. When a New York Times arts critic recently wrote about ‘Neanderthal TV’ he was referring not to a documentary on human evolution, but to programmes that feature ‘deeply flawed’ male characters with ‘antisocial tendencies’. The name can also be a source of humour. A rock band called The Neanderthals dresses in animal skins and sings simplistic songs about girls. We think this is all unfair.

Too often the Neanderthal story is told simply as a backdrop to our own, a reflection of the same obsession with our own species found in our creation stories. Yet there is a gentle counter-current to this sapiens-centrism, a growing sense of collective guilt that appears in the most unlikely places. We once came across a bottle cap that, for no clear reason, declared: ‘The brain of Neanderthal man was larger than that of modern man.’ It was a reminder that, of all the large mammal species whose extinction we have witnessed in recent millennia, at least one seems to have been our equal in brain capacity, if not in humanity.

In recent years new research has pulled the Neanderthals much closer to us. Not only did they have brains as large as ours (though their skulls had a different, flatter shape), they also buried their dead, cared for the disabled, hunted animals in their prime, used a form of spoken language and even lived in some of the same places as the modern humans who were, broadly speaking, their contemporaries. They could not have survived, even in warmer times, had they not mastered fire and worn clothes. Though they relied heavily on meat, they consumed seeds and plants, including herbs, and could fish and harvest sea food. These are all behaviours that at some point were thought to be exclusive to ourselves.

A golden age of research

The pace of progress in our understanding of the Neanderthals keeps accelerating. Thanks to some breathtaking recent discoveries and scientific advances, we can now examine the story of the Neanderthals in greater depth than was previously thought possible. This is truly the golden age of Neanderthal research, making it the perfect time to see how all the strands of evidence fit together into a narrative of the rise and fall of a long underestimated type of human.

When we started studying the Neanderthals in the early 1990s as graduate students, much of what is now our current knowledge was the subject of heated debate. Most of this debate revolved around the Neanderthals’ role in our own story. In those days, for example, it was not yet clear whether the Neanderthals and modern humans ever shared the same continent at the same time. (We now know they did.)

Archaeologists were then still absorbing the implications of a genetic study that supported the so-called Out of Africa theory, that all living modern humans can be traced back genetically to a single woman (or a small group of women) in sub-Saharan Africa. The entry of genetic evidence into archaeology exposed sharp divisions in the discipline. Although the Out of Africa theory was about the evolutionary trajectories of all modern human populations, Europe and the Neanderthals were a key part of the debate. The dominant question in Neanderthal research at the time was whether they were part of our evolutionary ancestry or whether they had been replaced, either after a hiatus or by being out-competed – perhaps even killed off – by modern humans who had originated in Africa and migrated into Europe.

In 1993 Chris Stringer and Clive Gamble published their landmark volume, In Search of the Neanderthals, which put forward the case that modern humans replaced, rather than evolved from, the Neanderthals. Little did we realize that this was just the beginning of a wave of new insights and evidence about our evolutionary kin, and that the question of our replacement of the Neanderthals would re-emerge forcibly with further genetic studies.

Since then, there have been several major news stories every year on the Neanderthals. Atapuerca, a cave network in Spain, has produced the remains of around thirty individual ‘proto-Neanderthals’, an astonishing total if we consider that the number of Neanderthal individuals in the fossil record is only a few hundred. In 2007 a discovery from a different part of Atapuerca pushed definitive evidence for the earliest occupation of Europe, possibly by a Neanderthal predecessor species, over the 1-million-year mark for the first time. And more recently, a team in Germany led by Svante Pääbo (see p. 143) has made staggering claims based on the identification of Neanderthal DNA. It can be hard at times to make sense of this flood of information.

The number of scientific disciplines contributing to Neanderthal research in recent years has multiplied. Our knowledge has been boosted by a variety of specialists: geologists who drill sediments from the deep ocean floor and take ice cores from glaciers covering Greenland and Antarctica; archaeologists who sieve and sort through every ounce of dirt from an excavation looking for anything from seeds to rodent teeth; geneticists who put on sterile clothing to drill Neanderthal bones in the hope of finding bits that have neither fossilized nor been contaminated by flakes of their own skin in order to extract ancient DNA; and, of course, those archaeology students who kneel down with a trowel and a brush to excavate squares of earth, layer by layer, carefully recording the location of every stone tool or bone they might find (and hoping they aren’t embarrassed by confusing the two).

We now know more than we ever thought we could about the Neanderthals and their world. They have emerged as more accomplished in their everyday lives and more complex in their social behaviour than we imagined. This makes it all the more puzzling why this separate form of human, nearly as advanced biologically and culturally as ourselves, became extinct. The fate of the Neanderthals has been a mystery for more than 150 years.

The valley of the new man

But before we consider the Neanderthals’ fate, let us explore their discovery. There is a satisfying irony in the fact that we discovered our former human rivals in the course of supplying the energy and materials for global domination. It is no exaggeration to say that our knowledge of the Neanderthals was an unexpected by-product of industrial mining in the 19th century. As engineers were digging ever deeper for minerals, evidence was fast accumulating about the Earth’s past.

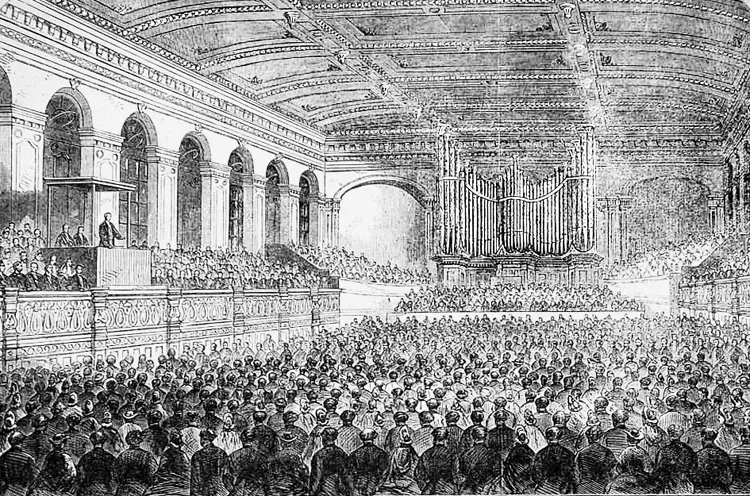

‘There will be very soon little left to discover,’ was how The Times of London described the science of geology in 1863. The occasion was the British Association for the Advancement of Science’s annual summer meeting in Newcastle. The conference was enormous, with scores of mineralogists, geologists, chemists and others from dozens of burgeoning scientific disciplines. It was here that a little-known professor called William King became the first person to use fossil evidence to name an extinct species closely related to our own.

Sir William Armstrong celebrates the rapid progress of science in his keynote address to the 1863 meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, as depicted in an engraving from the Illustrated London News. Later in the conference, the Neanderthals received their scientific name, Homo neanderthalensis.

Professor William King, of Queen’s College, Galway, Ireland, who suggested the name ‘Homo Neanderthalensis’.

Drawing of the original Neanderthal skull from Man’s Place in Nature by Thomas Huxley.

The conference’s keynote speaker was Sir William Armstrong, a local industrialist and engineer. In celebrating the fast pace of discovery, he noted that in short order Charles Darwin had finished On the Origin of Species, John Speke and James Grant had found the source of the Nile and Charles Lyell had published Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man, which extended human history deep into the past. One of Lyell’s protégés, Professor King had come to the meeting from Queen’s College, Galway, in Ireland to present a short paper on a recent discovery from a lime quarry near Düsseldorf, in what was then Prussia. Some sixteen years earlier he had been forced out of his job as curator of the Newcastle Museum. Now he hoped to return in triumph.

In his paper King discussed human-like bones that had turned up in a cave (Feldhofer) in the Neander Valley seven years earlier. The collection included ribs, arm and leg bones and the top of a skull that featured a protruding crest above the eyes. In a departure from the prevailing view that the bones belonged to a deformed member of our own species, King argued that they dated to the glacial period and were closer to the chimpanzee than to any modern human. We now know that King was wrong on this last point, for the individuals from the Neander Valley were much closer to modern humans than chimpanzees. But he was correct in his more startling conclusion, when he argued that they were fundamentally different from all living humans.

He proposed ‘to distinguish the species by the name Homo Neanderthalensis’ after the Neander Valley where they were discovered. In the process, he unwittingly immortalized a 17th-century psalmist, Joachim Neumann. Following the Philhellenic fashions of the 19th century, Neumann’s last name (literally ‘new man’) was translated to the Greek ‘Neander’ and then attached to the valley (‘thal’ in German) where he penned his psalms. Thanks to King, members of the long-extinct species unearthed there have been known by the wonderfully ironic name of Neanderthals (people from the valley of the new man).

Before that day, the nearest known species to humans were living apes. Today there are more than twenty named species in our family tree since the split from the apes, and with recent discoveries such as Homo floresiensis – the so-called ‘Hobbit’ – in Indonesia in 2003 and the Denisovans from Siberia whose genes were identified in 2010, it seems likely that this number will continue to increase.

Before the discovery in the Neander Valley in 1856, other Neanderthal remains – a small child’s skull from Eng...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- About the Authors

- Other Titles of Interest

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Chapter One: A Long Underestimated Type of Human

- Chapter Two: The First Europeans: 1 million to 600,000 years ago

- Chapter Three: Defeating the Cold: 600,000 to 250,000 years ago

- Chapter Four: Meet the Neanderthals: 250,000 to 130,000 years ago

- Chapter Five: An End to Isolation: 130,000 to 60,000 years ago

- Chapter Six: Endgame: 60,000 to 25,000 years ago

- Chapter Seven: Still With Us?

- Bibliography

- Sources of Illustrations

- Index

- Copyright