![]()

STAND-OFF IN A GARDEN

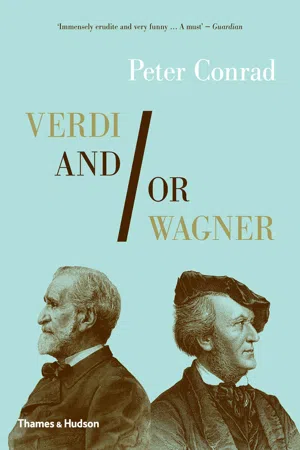

This is surely as close as they ever got to each other: they stand, with a buffer zone of lawn between them, in a garden at the edge of Venice beyond the Arsenal, where the floating city begins to trail off into the lagoon. Despite their proximity, each pretends to be alone. A path relegates them to separate patches of grass; one of them hides in the shrubbery, while the other, asserting his right of occupancy, stands on a slope and stares across the water. Their memorials are modest enough, since they are not the kind of men who rear on bronze horses or balance atop columns like conquerors. Reduced to heads, they are set on pedestals that state their names. The one who skulks in the bushes is Giuseppe Verdi. The other – his jaw set at a confrontational angle like a mountain ledge as he scans the horizon for detractors, or perhaps for devotees on pilgrimage to his shrine – is Richard Wagner.

So comparable but so incompatible, they were born in the same year – Wagner on 22 May 1813 in Leipzig, Verdi on 10 October 1813 in Le Roncole near Busseto in the Duchy of Parma. For official purposes Wagner’s father was a clerk in the police service, although Richard may have been the son of a Jewish actor called Ludwig Geyer whom his mother, widowed when the boy was six months old, soon married. Verdi’s background was less shadowy, though not quite as humble as he liked to claim when calling himself a rough-hewn peasant: his father kept an inn that doubled as a village grocery.

As their busts testify, Verdi and Wagner were both cultural heroes, but of different kinds – a native son attached to the soil versus a wandering exile; a tribune of the people versus a dictatorial aesthete; a man of progress versus an atavistic myth-maker; a spokesman for afflicted humanity versus a creator of gods, giants, dragons, dwarfs and fairies. Like saviours, both composers appeared as if in answer to a prayer. When Verdi’s first opera, Oberto, was performed at La Scala in November 1839, a critic remarked that the audience’s grateful, almost worshipful reaction meant ‘We have a Messiah.’ A less enthusiastic reviewer in Leipzig in 1845 complained that Wagner was being touted as ‘the Messiah of opera’. By the end of their lives they had turned into incarnations of their times, the Zeitgeist made flesh. All of Italy grieved when Verdi died on 27 January 1901, and the government decreed a period of mourning longer than that awarded to a monarch. The Italian parliament devoted a session to eulogizing him, during which one of the deputies justly claimed that Verdi was more than a man of the nineteenth century: he personified the century, which lived in and through him. Wagner, however, did not wait for others to promote him posthumously to the role of legislator for the age. He knew, he said, that his purpose was ‘to tell the century all that we have to say to it!’

Despite their affinities, Verdi and Wagner spent the best part of the nineteenth century managing not to meet, and since the early twentieth century they have stood in the Venetian garden at a diplomatic distance, not quite turning their backs on each other but also stubbornly declining to reach an accord. The differences were personal, and the busts, for all their second-hand crudity, hint at that. In his shelter of leaves, Verdi craves anonymity: he despised publicity, shunned high society, and prematurely retreated from the cities where his operas were performed to live like a farmer on his estate at Sant’Agata near Busseto. Across the way, Wagner on his small eminence confronts the world rather than withdrawing from it. He is a candidate for a hero’s life, prepared for struggle and intent on prevailing, proud of his isolation. The planes of Wagner’s clean-shaven face were already sculptural before anyone attempted to carve them in marble, but Verdi is less sleek and smooth, and his bust gives him the fringe of beard he always wore – another defence, like the encroaching leaves of his impromptu bower, against being seen and evaluated. Wagner has no arms: the brain in that armoured skull can apparently dispense with appendages. Verdi, however, is allowed the use of his right arm, which grips a roll of music paper against his chest. His hand makes a stout, dependable gesture of faith, like an American pledging allegiance to shared verities. One man is portrayed as a frowning mind, the other as a more sensitive being who translates emotions into song as if the heart’s affections had been directly transmitted – in crotchets and quavers that stand for spasms and palpitations – to the page he holds.

The pedestal that props up Wagner’s self-sufficient head has a squashier interior, a metaphorical recess of punctured flesh and spilt blood. On the plinth, a pelican’s scissory beak rends its breast to feed its jostling offspring, which pick at the exposed entrails. Ezra Pound, walking in the gardens near the end of his life, was asked by his minder what the low-relief medallion meant. ‘Toujours les tripes,’ he said: a vile daily diet of offal. In fact the self-rending bird is a religious icon, traditionally an emblem of Christ’s sacrifice for the sake of fallen mankind. Profanely reinterpreted here, it suggests the source on which Wagner drew for his last opera: ‘Was ist die Wunde’ asks the stricken Amfortas in Parsifal, wracked by what he calls a delicious pain, or ‘seligsten Genusses Schmerz’. The lesion is music, and it can only be healed by the touch of the spear that tore the gash in his body: the addict’s relief is a renewed dose. The icon suggests that Wagner made music by playing upon his overtaxed senses – an experiment in intensification that helped provoke the cardiac emergencies that finally killed him in Venice in 1883. The French poet Catulle Mendès, who visited him in Lucerne in 1869, said that Wagner’s small body trembled with excitement from head to toe, like a violin string plucked pizzicato. Verdi by contrast had the tough constitution of a countryman. During the 1840s, when he worked at a maddening pace to keep up with the commissions he received, he suffered repeated psychosomatic upsets, with stress unsettling his stomach and bowels or leaving him with a painful, scratchy throat. His heart, however, lasted him until 1901.

Friedrich Nietzsche thought Wagner ‘the most enthusiastic mimomaniac … who ever existed’, as hyper-emotional as a gesticulating opera singer. The undemonstrative Verdi had no interest in self-display, and the sentiments inscribed on the unrolling sheet of music held by the figure in the park are national not personal. The page is the chorus ‘Va, pensiero’ from Nabucco, sung by homesick Hebrew slaves in Babylon; in popular mythology, this lament turned into a yearning anthem for oppressed Italy. Wagner’s bust portrays him as a self-tormenting egotist, whereas Verdi is shown to be the choirmaster for an entire country. Nor did his bequest to the nation end with his art. The only reason for loving (or hating) Wagner is his music, but Italians continue to honour Verdi’s humane generosity as well as his genius. This was a man who built a hospital – which still functions – so that his tenant farmers and their families could receive immediate medical care on his estate; he intervened angrily when he learned that patients were served inferior food and the destitute made to pay for funerals. He also founded the Casa di Riposo in Milan, a rest home for impoverished musicians who had outlived their gifts, and endowed it with his royalties. When he died, Gabriele d’Annunzio tallied the nation’s debt to him in an ode, making all Italians Verdi’s grateful dependants. He nourished us, d’Annunzio claimed, like bread; his music was as vital as food, containing – as the poem says – all the sweet, rich savour of the earth.

The temperamental opposition between Verdi and Wagner was entrenched by geographical and cultural divisions. Theirs was a world still rooted in locality, suspiciously guarding its borders. When the hero in Tannhäuser makes his pilgrimage from Germany to Rome to seek a papal pardon, he travels through Italy with his eyes closed, not wanting to be distracted by the beauty of the landscape. Hedonistic enjoyment is for simple, pagan people; as a German, he prefers the more elevated calling of spiritual pain. Wagner did not share this abstinence, and in later life he fled to Italy during German winters, which is how he came to die in Venice. His son Siegfried even aligned his father’s operas with the work of Italian Renaissance painters: Lohengrin reminded him of Raphael, Tristan of Titian, Götterdämmerung of Tintoretto. Verdi likewise ventured beyond his native ground in quest of operatic subjects and on several occasions set plays by Schiller, whose characters – the radical bandits in I masnadieri, the Oedipal prince in Don Carlos – have the reckless moral insurgency that German romantics admired. But during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71 he reverted to an ancient hostility and denounced the modern Germans as Huns, wreckers of civilization. In 1882 he protested against Italy’s entry into the Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary, insisting that the country’s true ally was France.

Critics in the nineteenth century habitually contrasted sensual Italian song with the cerebral German symphony, claiming that Italians used music to express feeling, whereas for Germans it was a mode of thought. True to an inherited prejudice, Verdi pitied Wagner’s lack of a lyricism that came naturally to musicians in southern climates, and said that Wagner had chosen a hard road because the easier one was not open to him. On his side of the Alps, Wagner had little regard for Verdi’s melodic instinct. At work on Parsifal, he warned himself not to be ‘led astray by the melodies’: tunes were like sirens, beguiling the ear while they softened the brain. In 1863, writing to Mathilde Wesendonck about a concert tour, he sniffed at the musical diet of ‘Verdi etc.’ on which the Hungarians subsisted, and assumed that this explained their gratitude for his performances of his own music. In 1882 in Venice he heard a snatch of Verdi bellowed on the Grand Canal, probably by a gondolier, and scoffed at the fatuous sentiment of the unidentified aria and its mannered rhythm.

Although Verdi outlived Wagner by seventeen years, his last decades were soured by critical complaints that his own music had become Wagnerian. He reacted as indignantly as if he had been called a traitor. ‘Fine result after 35 years of career,’ he said in 1875, rejecting claims that he had dwindled into ‘an imitator of Wagner!!!’ Verdi was accused of abandoning the old Italian model of opera – where the plot was disposed of in recitative while the action intermittently paused for arias that vented ire or lust – and adopting the symphonic continuity of Wagner; now his orchestra challenged the dominion of singers who expected a more subdued, deferential accompaniment. The caricaturist Carl von Stur physically merged the two composers in a sketch published in the Viennese journal Der Floh in 1887. Otello, Desdemona and Falstaff look on from a corner while Verdi sails away in Lohengrin’s swan-powered dinghy. He has borrowed Wagner’s velvet smock and even wears his floppy beret, but bangs a drum and grinds a hurdy-gurdy as a sign that he has not quite managed to live down his bad Italian habits. The supposed change in Verdi’s style earned him an admirer he would just as soon have done without. In 1892 the conductor Hans von Bülow – Cosima’s first husband, who out of reverence for Wagner had pretended not to notice her adultery – sent him a message of contrition. Bülow explained his earlier hostility to Verdi as the bigotry of an ‘ultra-Wagnerian’ fanatic, and said how much he admired Aida and Otello. Unfortunately he addressed ‘the last of the five kings of modern Italian music’ as ‘the Wagner of our dear allies’: Verdi was therefore at best an alternative or an equivalent to Wagner, and the alliance between Bismarck’s industrialized Germany and backward Italy remained unequal. Verdi replied graciously, absolving Bülow of any sin. But to his publisher Giulio Ricordi he commented, ‘He is definitely mad!’

The story of the Venetian busts justifies Verdi’s grievance about his relegation to second place. The Wagner memorial arrived first, as if he had prior rights: twenty-five years before dying in the Palazzo Vendramin, he spent the winter of 1858–59 composing the second act of Tristan und Isolde in another palace on the Grand Canal. The city suited Wagner because its fluent instability matched his music, and after his death Venice seemed to retain a memento of his music in its swampy, opalescently humid air. In 1902 the French novelist Maurice Barrès described the score of Tristan as an exhalation from the lagoon. By then Wagnerism was a cult with adherents in all countries, which is why in 1908 a Berlin stockbroker commissioned the sculptor Fritz Schaper to carve the marble bust for the Giardini Pubblici. At its unveiling, a band wheezed through the processional entry of the Landgraf’s guests in Tannhäuser, with the invited audience listening in decorous silence. This was followed by the more pompous march across the rainbow bridge that leads Wotan and his royal family into Valhalla at the end of Das Rheingold. It had been played during rehearsals at Bayreuth in 1876 when Wagner, treading a gangplank, strode onto the stage of his new theatre. In Venice too the extract marked the apotheosis of the composer; the ironic asides of Loge, who foresees doom for the gods, and the complaints of the Rhinemaidens, whose stolen gold has paid for this plutocratic palace, were of course omitted.

Verdi was bemused by Venice. He made his first visit in 1843 to rehearse I Lombardi alla prima crocciata, and in a letter reported that it ‘is beautiful, it is a poem, but … I wouldn’t live here of my own accord’. Preoccupied throughout his life with planting trees, rearing animals and harvesting crops on his own land, he could not feel at ease in this illusory, ungrounded place. But once Wagner established a posthumous presence in the garden, Verdi’s absence became an embarrassment, and within six months Gerolama Bortotti’s bust was inaugurated; to mark the occasion, a band played popular tunes from half a dozen operas (not including La traviata which, as Verdi gruffly reported, was a ‘fiasco’ when first performed at La Fenice in 1853). A plaque on the pedestal significantly declares ‘A Giuseppe Verdi – Venezia’. Wagner – who depended throughout his career on handouts from kings, merchants and subscribers to his festival at Bayreuth – owed his monument to an individual’s devotion and his disbursement of private funds, but Verdi’s was the grateful donation of the city, paid for by the Consiglio Comunale. Verdi respected his customers, and even gave them the benefit of the doubt when they disliked his work. Wagner meanwhile composed a ‘music of the future’ which, he predicted, would only be understood when audiences and performers had acquired new reserves of physical stamina and new capacities for intellectual concentration; in his view art was not a product sold in the market but a gift evangelically handed down, like the Grail in Lohengrin or Parsifal, to a world that was as yet unready and probably unworthy. The busts measure the gap between Verdi and Wagner, and restate their disagreement about art’s purpose and its responsibilities. Is the garden path that separates the two men an uncrossable chasm?

||||||||||||||||||

I was startled to discover them here, on a desultory evening stroll in Venice a few years ago. I came upon Verdi first; I was going nowhere in particular, and could easily have been wandering in the other direction, which would have favoured Wagner. The surprise derived from finding them together, and from having to think of them sharing the same disputed space.

There are thousands of books on Wagner and there must be a few hundred on Verdi, but I know of only a couple that purport to compare them. In El Genio en su Entorno, Carmen de Reparaz tours their working environments – or rather some of them, since the Wagnerian half of her book stays at Triebschen, the villa outside Lucerne where Wagner lived for six years between his expulsion from Munich in 1865 and his move to Bayreuth in 1872. I was excited by the title of Ernö Lendvai’s Verdi and Wagner, then found when I read it that its real concern is Hungarian folk music and the theoretical system devised by Zoltán Kodály to explain its modal rather than tonal structure; Verdi and Wagner interest Lendvai as unwitting forerunners of Béla Bartók and his ‘polymodal chromaticism’. Most of the study is about Verdi’s Falstaff, and the only Wagnerian passage discussed is the heroine’s recriminatory narrative in the first act of Tristan und Isolde. An epilogue offers to engineer ‘The Meeting of Tristan and Aida on the Deck of the Computer’ in diagrams that compare the scampering of the temple dancers in Aida with the motif that signifies death in Tristan und Isolde. Three pages, which soon diverge into another astronomical and astrological salute to Kodály, are not enough to make the match. With the debatable exceptions of these two books, Verdi and Wagner remain in their mutually antagonistic realms.

During their lifetimes, each kept a wary eye and a disapproving ear on the other. In 1865 Verdi heard the overture to Tannhäuser at a concert in Paris and pronounced it ‘matto’, mad. Wagner was brusquely intolerant when he attended a performance of Verdi’s Requiem in Vienna in 1875: in her diary Cosima, by now Wagner’s wife and slavish amanuensis, noted that there was no point in discussing the piece. Verdi at least pondered Wagner’s theories, and in 1870 asked to have copies of his essays sent from Paris. He agreed with Wagner’s arguments in favour of a sunken orchestra pit, as at Bayreuth, though for practical not mystical reasons. Rather than wanting a cavity from which sound with no visible source would suffuse the air, Verdi simply thought it absurd that musicians in tailcoats and white ties should be jumbled in the same sightline with the Egyptians, Assyrians or Druids onstage. He told his friend Clarina Maffei not to think of Wagner as ‘a fierce beast’, a distempered savage, but he was equally concerned to deny him the role of prophet. The idea of an aesthetic religion was anathema to Verdi, which is why in 1893 he likened Wagner’s endless melody to the tomb of Mohammed, supposedly suspended between heaven and earth.

In the same mischievous letter Verdi joked that he had advanced beyond the concise, catchy tunes of Traviata and Rigoletto and now, at the age of eighty, intended to match Wagner’s longueurs by composing ‘an opera in twelve acts plus a prologue and an overture’ that would be ‘as long as all nine of Beethoven’s symphonies put together’. He was ironically in earnest when boasting of his stamina. He had recovered from the sixteen years of inertia that separated Aida in 1871 from Otello in 1887, then managed a second revival or resurrection with Falstaff, composed between 1889 and 1892. He must have felt, in moments of elation like this, that he could do anything. Wagner, not bothering to be competitive, made casual fun of Verdi. In Venice a few months before his death he amused Cosima by improvising ‘something à la Verdi and à la Chopin’ at the piano. They were filling in time before supper; this was culinary music, useful as an aperitif. Such dismissals concealed a rankling envy that Wagner never openly expressed. In 1866 he was piqued when the city of Nuremberg chose to entertain Ludwig II of Bavaria, his besotted patron, with a performance of Verdi’s Il trovatore. Perhaps the slight prompted him to complete Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, which honours the city as the home of a German renaissance; he had already urged the king to make Nuremberg his capital, which gave Wagner reason for feeling proprietorial about the place. In 1880 he had a jealous twinge when brooding about Ludwig’s failure to summon him back to Munich. What rankled was a rumour that the king had been amusing himself with private performances of operas by other composers, including Aida. In July 1873 Cosima heard an open-air concert of military music in Bayreuth, and was taken aback when the brassy din concluded with Elsa’s bridal procession from Lohengrin. In the unaccustomed context, Wagner’s music resembled ‘a captive princess in the vulgar triumphal parade, sad and touching’. Cosima’s simile is startling: does it allude to the enslaved Aida, who watches the humbled king of Ethiopia led in triumph through Memphis?

Verdi kept an open mind about Wagner, a...