![]()

Chapter 1 Demonstrations of Versatility

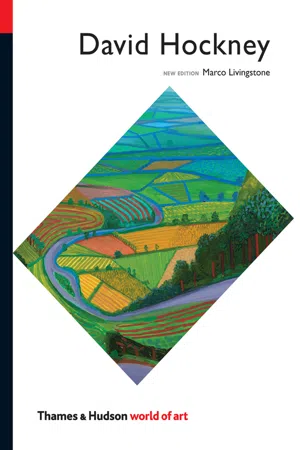

David Hockney has commanded greater popular acclaim than any other British artist of this century. Born in Bradford, Yorkshire, in 1937, he had acquired a national reputation by the time he left London’s Royal College of Art with the gold medal for his year in 1962. The artists with whom he was associated at the College, notably R. B. Kitaj, Allen Jones, Peter Phillips, Derek Boshier and Patrick Caulfield, heralded by the press as the young stars of British Pop Art, all enjoyed early success, but Hockney from the start was in a category of his own. In 1961 he was awarded a prize for etching at the ‘Graven Image’ exhibition in London, as well as a painting prize at the John Moores Liverpool Exhibition. Before finishing his studies he had already been approached by a Bond Street dealer, John Kasmin, with whom he had his first one-man show in 1963, aged only twenty-six. In 1967 he was awarded first prize in the John Moores Exhibition, and three years later he was honoured with the first of several major retrospectives which have established his reputation internationally. His works now fetch higher prices than those of almost any living British artist.

It is doubtful whether any British artist since the Second World War has attracted so much newspaper coverage and been the subject of so many interviews. A number of substantial catalogues and specialized studies have been produced about his work. Hockney himself has published two volumes combining autobiography with theory (1976 and 1993), a picture book in paperback (1979), and monographs devoted to his Paper Pools series (1980) and to his trip to China (1982), all originating with the same British publisher, Thames & Hudson.

The present study might be regarded as yet another instance of the way in which the Hockney promotional enterprise has been fed. Surprisingly, however, for an artist who has been the centre of so much attention, this is the first critical study of his work. In view of the public’s interest in Hockney’s art, one can legitimately ask why no other book, nor even any substantial articles, appeared until well into the 1980s. Was it that Hockney was acceptable only as a social phenomenon rather than as a serious artist? Did other writers and publishers consider that their reputation might be discredited if they concerned themselves with his work?

Since the time of Courbet and increasingly during our own century, the committed artist has been considered to be in opposition to the taste of his time. In his essay on The Dehumanization of Art (1925), José Ortega y Gasset proposed the view, now widely accepted in the art world, that serious new art is not only unpopular but essentially ‘anti-popular’. In these terms, serious achievement in art is measured in inverse proportion to its popularity, for the two have been defined as incompatible.

Hockney’s work appeals to a great many people who might otherwise display little interest in art. It may be that they are attracted to it because it is figurative and, therefore, easily accessible on one level, or because the subject-matter of leisure and exoticism provides an escape from the mundanities of everyday life. Perhaps it is not even the art that interests some people, but Hockney’s engaging personality and the verbal wit that makes him such good copy for the newspapers. He may, in other words, be popular for the wrong reasons. But does this negate the possibility that his art has a serious sense of purpose?

In the view of some respected critics, such as Douglas Cooper, Hockney is nothing more than an overrated minor artist. To this one can counter that Hockney might seem minor because it is unacceptable today to be so popular, rather than because his work is lacking in substance. Hockney himself is not self-deluding; he is aware of his limitations and thinks that it is beside the point to dismiss his work because it does not measure up to an abstract concept of greatness. Hockney does not claim to be a great artist and is aware that only posterity can form a final judgment on his stature.

It has been said that Hockney’s work is shallow because of the life he leads and the people with whom he surrounds himself. Hockney is aware of this charge but finds it incomprehensible: ‘I know some people think one leads a glamorous life, but I must admit I’ve never felt that myself. Even when you’re sat here in Hollywood with a swimming pool out there, I still feel my life is just as a working artist, actually. That’s the way I see it.’ He feels no particular need to demonstrate his cultural credentials or political awareness in his work, although he is extremely well informed not only about current events but also about literature, music and the arts generally. The accusation that his world view is vacuous and circumscribed is based primarily on the drawings which he has produced in luxury hotels on his travels round the globe [123, 129]. It would be highly misleading, however, to base one’s estimation of Hockney’s art on such drawings, which he himself regards as a pastime peripheral to his main concerns. It is not unusual for an artist today to travel or to stay in luxury hotels, but Hockney is rare in spending his quiet moments drawing, through his very devotion to the activity. It would be wrong to condemn him for wanting to produce art in most of his waking hours.

Perhaps the most serious criticism of Hockney as an artist is that he makes superficial gestures towards Modernism as an illustrator would, rather than committing himself fully to a Modernist approach. Hockney recognizes the extent to which his own work has been conditioned by Modernism, which he regards as ‘one of the golden ages of art’, but takes issue with what he regards as the academicism of what is known as Late Modernist art. It may be that Hockney is trying to reconcile two things which in our own day would seem to be irreconcilable: serious aesthetic intentions and ease of communication with people outside the art world. It is a dangerous task, but one that is worth pursuing if the artist is to retrieve his position as a working member of society at a time when his isolation has reached an almost intolerable level.

Hockney’s popularity and commercial success, even if they have not destroyed his integrity, have nevertheless proved an inhibiting force. ‘There comes a point where you see it all as completely empty,’ says Hockney, ‘being a popular artist to the extent that people who are not necessarily interested in art know about things or take some little interest. I think that now for me it’s a burden. It’s a bit hard to deal with, and it wastes time as well.’ It is partly to escape the public glare that Hockney feels compelled to keep changing his country of residence, moving each time that he finds the social pressures have become too difficult to bear. Inevitably his work charts the path of his life, not only from place to place but also as a withdrawal into a private world populated mainly by close friends.

Hockney, of course, is not wholly blameless for the situation in which he finds himself. His decision to dye his hair blond during his visit to New York in 1961, for instance, is indicative of his desire to be noticed both as a person and as an artist. He ‘reinvented’ himself, to use his own term, in a sense making himself the trademark with which to market his work.

The confusion between man and work implied in the personal act of dyeing his hair is not altogether inappropriate, since to an unusual degree Hockney has consistently based his art directly on his experiences and on his relationships with other people. To dwell on biographical details, however, would be to promote further the serious misrepresentation of Hockney as a colourful personality rather than as a committed artist. As one of those rare painters who is as well known for who he is as for what he has achieved, he has suffered in terms of credibility in that his social role has tended until now to obscure the importance of the art. The popular appeal and easy seductiveness of that art have likewise masked its sense of purpose. It is necessary to redress the balance.

2 Portrait of My Father, 1955

Hockney’s astonishing self-confidence, nevertheless, provides a key to understanding his development. The bravado is evident in the generic title of his last student paintings, exhibited as a group in the 1962 ‘Young Contemporaries’ exhibition in London: Demonstrations of Versatility [27, 28, 29]. It is a phrase, however, which also reveals the paradoxical coherence of his work at that time [29, 30]. In these pictures Hockney insisted that any style could be chosen at will, that any form of representation, any type of image, any subject or theme was fit material for a picture. Like some of his colleagues at the Royal College of Art, Hockney was in search of a ‘marriage of styles’ that would free him from the limitations of any one way of picturing the world.

Unlike the change of Hockney’s hair colour, the declaration of freedom and detachment in his art was not achieved overnight. His decision to play with style was conditioned to a large degree by his own earlier history and training. It was because he had already experienced the strait-jacket of subservience to particular styles that he especially welcomed the prospect of emancipation through the deployment of contradictory modes.

As a teenager in the mid- to late 1950s, Hockney, like many art students, experimented with various ways of making pictures, seeking a single workable process but ending, through restlessness and changes of heart, with a diverse and apparently contradictory body of work. At Bradford School of Art from 1953 to 1957 Hockney received a traditional training which inculcated a respect for close observation from life, for subdued handling of paint surface and colour, and for drawing as the essential process for transferring perceived sensations to canvas. The works made at this time betray an unfa...