![]()

Chapter 1

1841–77

Renoir to age 36;

a Bohemian Leader among the Impressionists;

Model Lise and their Secret Children, Pierre and Jeanne

In November 1861, when he was only twenty, Renoir made one of the most fortuitous decisions he ever took: to study in the Parisian studio of the Swiss painter, Charles Gleyre. A photograph around this time reveals that Renoir was a serious, intense young man. Gleyre’s studio was simply one of many that fed into the École des Beaux-Arts (the government-sponsored art school in Paris), where students learned anatomy and perspective through drawing and painting. The men Renoir met at Gleyre’s would become some of the most important companions of his life. About a year after he arrived, first Alfred Sisley in October, then Frédéric Bazille in November and lastly Claude Monet in December 1862 became fellow students.1 On 31 December 1862, the four were already close friends when they met at Bazille’s home in Paris to celebrate the New Year together.2 Through these friends, Renoir met Paul Cézanne and Camille Pissarro, studying nearby at the Académie Suisse. These artists would not only become lifelong friends, but would also be of critical importance for Renoir’s artistic development. In his early twenties, Renoir also made the acquaintances of Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas. Through them, he later met the two women artists, Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt. By the early 1870s, all of these painters would form the core of the Impressionist movement. Renoir’s charming, gregarious nature allowed him to make friendships despite his lower-class origins. He differed from his new artist friends in that only he came from a lower-class artisan family. The others were from a higher social class, giving them more education and better artistic connections. Bazille, Cassatt, Degas, Manet, Morisot and Sisley were from the upper class, while Cézanne, Monet and Pissarro were from the middle class. When Renoir was around forty, he summarized the origins of his training: ‘Not having rich parents and wanting to be a painter, began by way of crafts: porcelain, faience, blinds, paintings in cafés.’3 Despite his artisan beginnings, Renoir’s more affluent friends saw his lower-class roots as no impediment to his artistic genius. From the beginning of their friendships, when Renoir was short of money to buy paints or food, or needed a place to work or sleep, he was not averse to asking his friends for help, and they were generous, often treating him as if he were a member of their family. It was not only his modest origins that distinguished Renoir, but also his nervous disposition, which was exacerbated by his status as an outsider. Nonetheless, he was beloved and held in high esteem by many. Edmond Maître, an haute-bourgeois friend of Bazille and a friend of the young painter Jacques-Émile Blanche, expressed his astonishment and pleasure that someone from such humble origins and with such anxiety was able to be a man of character and value. Blanche quoted Maître’s description of Renoir aged forty-one: ‘“When Renoir is cheerful, which is rare, and when he feels free, which is just as rare, he speaks very enthusiastically, in a very unpredictable language that is particular to him and does not displease cultured people. In addition, there is within this person such great honesty and such great kindness, that hearing him talk has always done me good. He is full of common sense, on a closer look, yes, common sense and modesty, and in the most innocent and quiet manner, he relentlessly produces his diverse and refined work, which will make future connoisseurs’ heads spin.’”4

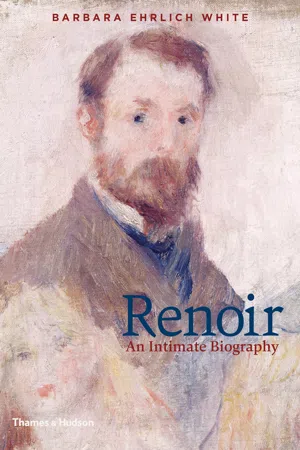

Renoir, 1861. Photographer unknown

Renoir’s background was more modest than Maître knew: the painter’s grandfather, born in 1773, during the reign of Louis XV, in Limoges in central France, had been left as a newborn on the steps of the town’s cathedral. That Renoir’s grandfather had been abandoned might explain the artist’s later sympathy towards his own and others’ illegitimate children. His grandfather’s birth certificate reads: ‘The year of our Lord 1773 and on the eighth of the month of January was baptized…an abandoned newborn boy on whom was bestowed the name François.’5 Abandoned children were given the last name of their adoptive family. A Limoges family named Renouard took in the child. Twenty-three years later, when François married, the scribe asked for his last name. At the time of his betrothal in 1796, neither François nor his bride-to-be could read or write. When François said ‘Renouard’, which, in French, is pronounced the same as ‘Renoir’, the scribe wrote ‘Renoir’ and thereby invented the family name, since there were no Renoirs in Limoges previously.6 At the time of his marriage, twenty-two-year-old François was a wooden-shoemaker. His bride, Anne Régnier, three years his senior, came from an artisan family in Limoges: her father was a carpenter and her mother, a seamstress.

François’s eldest child (Renoir’s father), Léonard, was born in Limoges in 1799 during the French Revolution.7 He became a tailor of men’s clothing. When twenty-nine, he married a dressmaker’s assistant, Marguerite Merlet, aged twenty-one, who was born in the rural town of Saintes.8 Her father, Louis, was also a men’s tailor; her mother had no profession. Renoir’s parents had seven children of whom the first two died in infancy. The artist was the fourth of the surviving five. Renoir and his three elder siblings were born in Limoges. At Renoir’s birth, Pierre-Henri was 9 (born in February 1832), Marie-Elisa (called Lisa, born in February 1833) was 8 and Léonard-Victor (called Victor, born in May 1836) was 4½.9

Pierre-Auguste was known simply as Auguste. His birth certificate states: ‘Today, 25 February 1841, at 3 in the afternoon…Léonard Renoir, 41-year-old tailor, residing on boulevard Sainte-Catherine [today boulevard Gambetta]…presented us with a child of masculine gender who would have the first names Pierre-Auguste, born at his home this morning…to Marguerite Merlet, [Léonard’s] 33-year-old wife.’10 When the artist was born, his parents had been married for thirteen years. Since the family was Catholic, on the day of his birth, Pierre-Auguste was baptized at the church of Saint-Michel-des-Lions.

When Renoir’s paternal grandfather died in May 1845, Renoir’s father moved his family to Paris.11 At this time, many tailors from the provinces were drawn to the French capital whose population was then under a million.12 The family travelled by the only available means of transport, a horse-drawn carriage. They found lodgings near the Louvre museum and the Protestant church, the Temple de l’Oratoire, on rue de la Bibliothèque, now in the first arrondissement.13 Here, when Renoir was eight, his youngest brother, Victor-Edmond (called Edmond), was born in May 1849.

A year prior to Edmond’s birth, when Renoir was seven, and for the next six years, he went to a Catholic school run by the Frères des Écoles Chrétiennes (Brothers of Christian Schools). At the same time, Renoir was chosen to sing in Charles-François Gounod’s choir at the church of Saint-Eustache in central Paris (from 1852, Gounod was the conductor of the Orphéon Choral Society in Paris). Despite being in a Catholic school and choir, after his youth, according to his son, ‘Renoir seldom if ever set foot in a church.’14

At some time between 1852 and 1855, because of Baron Haussmann’s modernization of Paris, Renoir’s family was evicted from their old apartment.15 Haussmann’s renovations replaced old, narrow, dirty streets and crumbling buildings with wide, tree-lined boulevards with elegant structures and effective city sewers. The Renoirs moved a few blocks away to 23 rue d’Argenteuil in today’s first arrondissement. That apartment’s archives state that a men’s tailor, Léonard ‘Raynouard’, rented rooms on the fifth and sixth floors (America’s sixth and seventh floors). The building was described: ‘There is a store and thirty-three rented apartments for industrial and construction workers of modest means.’16 Renoir’s parents and their five children lived in three small rooms on the fifth floor. Their sixth-floor room was probably used for Léonard’s tailoring business and for Marguerite’s dressmaking.17 The Renoir family stayed at this address until 1868, when Léonard and Marguerite retired to the suburb of Louveciennes. Having Renoir’s childhood home near the Louvre was a happy coincidence, since this great museum had been free and open to the general public at weekends since 1793, and artists could enter any day of the week.

Renoir’s eldest brother, Pierre-Henri, followed the family tradition and became an artisan. He trained to be a medallist and gem engraver under Samuel Daniel, an older Jewish man. Daniel took Pierre-Henri under his wing, introducing the young man to his companion Joséphine Blanche, a seamstress, and to their (illegitimate) daughter Blanche Marie Blanc, who was nine years younger than Pierre-Henri. Daniel was Blanche’s legal guardian (tuter datif), and the family lived at 58 rue Neuve Saint-Augustin. In July 1861, Pierre-Henri and Blanche married, so Renoir had a sister-in-law who was both illegitimate and half-Jewish.18 When Daniel retired in 1879, Pierre-Henri took over his engraving business. By this point, he had become an authority on the engraving of interlaced ornaments and had, in 1863, published a manual of monograms that, four years later, was translated into English as Complete Collection of Figures and Initials.19 Pierre-Henri later wrote and published two other books.20 The painter Renoir’s various attempts at writing for publication in 1877, 1884 and 1911 were modelled on his older brother’s examples.

In 1854 when Renoir was twelve or thirteen, his family’s financial needs required that he leave school and go to work. His parents decided that he should follow Pierre-Henri into an artisan trade; it could well have been that Henri’s employer was friends with to Théodore and Henri Lévy of Entreprise Lévy, who were described as ‘bronze manufacturers’ and ‘painters, decorators, and gilders on porcelain’.21 Since Renoir showed artistic ability and since the family came from Limoges, a city renowned for porcelain, his parents thought he might be good at painting on porcelain vases, plates and cups. As a trade, it was closest to easel painting, so that apprentices became skilled in painting. Such workers could also earn substantially more per day than the 3.6 francs that tailors typically earned.22 Renoir began an apprenticeship at the porcelain-painting workshop of Lévy Frères at 76 rue des Fossés-du-Temple (now rue Amelot, eleventh arrondissement), where he probably worked for four or...