![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Who Are the Europeans?

Where did the people of Europe come from? That question has sparked curiosity for millennia. Tribes and nations developed origin myths for lack of better knowledge. Much that we would like to know is lost in the mists of prehistory. Anthropologists and archaeologists have long been labouring to shine a light into that forgotten past. They have achieved much. Most scholars now accept that our distant forefathers emerged in Africa to people the globe.1 Despite mighty barriers of desert, sea and mountain, anatomically modern humans had spread right across Asia and Europe before the last Ice Age forced them into habitable pockets amid the wastelands. [1] Only after that crisis had passed did our ancestors begin to take up farming, the first step on the way to civilization.

Yet trenchant disagreements remain over many of the particulars. Was farming spread into Europe by immigrants or by resident hunter-gatherers taking up agriculture? Why at the dawn of history were people from India to Ireland speaking languages of remarkable similarity? Did migrating Neolithic farmers bring with them the prototype of the Indo-European languages? Or did later Copper and Bronze Age herders do so? Or can we explain this pattern without migration?

These issues have been debated for decades. Others have more recently emerged. The spread of farming was traditionally pictured as one long wave inching its way across the continent of Europe from the Near East over thousands of years, whether by the movement of people or ideas. In the 1990s some archaeologists began to dissent. A new model appeared of farmers leapfrogging their way over previous settlements to create new colonies. Newer still is the idea of farmers arriving in Europe not in one wave, but a complex series of them. Could this be true?

The burgeoning field of population genetics offers hope of resolving such wrangles. Within us all we carry evidence of our ancestors. Now that we can read our own code, what stories of our past can it reveal? Ancient population movements can leave a trail in our DNA, pointing to distant relatives we didn’t know we had. It was clues from the genes of living people that provided the conclusive evidence, not only that Homo sapiens spread out of Africa, but that the most likely route was across Arabia (see p. 21).2

1 The expansion of anatomically and behaviourally modern humans out of Africa. Times and routes are very uncertain. KYA = thousand years ago.

When James Watson and Francis Crick described the spiral-staircase structure of DNA in 1953,3 we were a long way from being able to read its code. Their breakthrough was the understanding of how the code worked. Previously, the mechanism of genetics had been a mystery. Gregor Mendel, working in his monastery garden in the 19th century, had worked out some of the basic rules of inheritance by cross-breeding peas. How were the instructions for inheritance passed on from generation to generation?

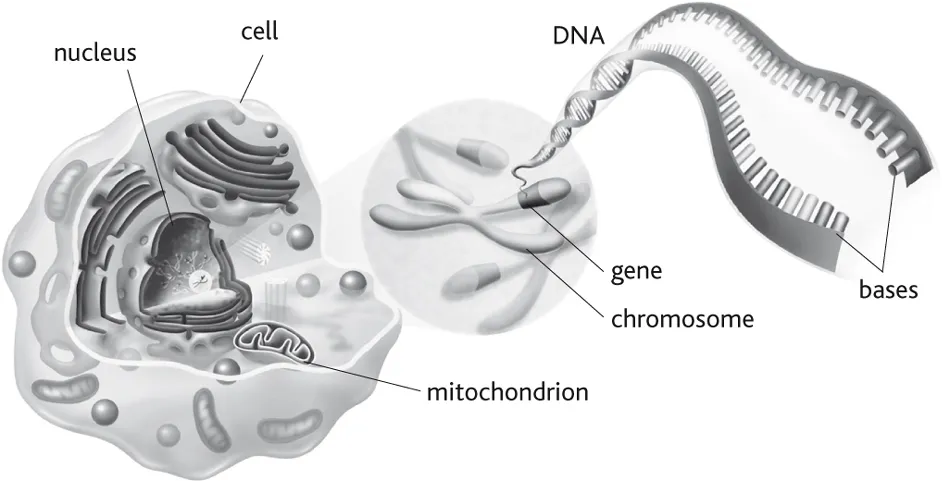

Inside the cells of all living organisms – in the nucleus of each cell – lives the code for making the organism. [2] Its building blocks are just four bases. That simplicity makes it so adaptable that it can code for anything from a virus to an elephant. Adenine (A) on one strand of the double spiral of DNA pairs with thymine (T) on the other. Guanine (G) pairs with cytosine (C). The sequence of these bases is the genetic instruction book. Before it could be decoded, it needed to be transcribed. Geneticists transcribe it into one long chain of letters such as AGGGTTACC and so on. The human genome has around three billion of these base pairs. So mapping the whole human genome was a mammoth task. Working drafts were published in 2001.

2 Diagrammatic representation of the key structural features of the cell and DNA.

Another part of our DNA had already been sequenced. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is found not in the cell nucleus, but in energy-generating mitochondria throughout the rest of the cell. Each mitochondrion is only 0.0005 per cent of the size of the nuclear genome, but there are hundreds or thousands of mitochondria per cell. MtDNA is also different in another way. It is passed down exclusively from mother to child. Picture an unbroken chain of life from the earliest humans through countless generations to your maternal grandmother and your mother and finally down to you.

How exactly is it passed down? The two strands of the double spiral can unzip themselves and then latch on to pairing molecules to create two identical spirals. So your mtDNA should be exactly the same as your mother’s. Sometimes, though, there are faults in replication. You could see it as a typing error in those chains of letters. Such errors, often called mutations or variants, can tell us a lot. If a sequence variant is found in you, but not in your mother, then we can be certain that it occurred in you. If you are female, it will be passed down to your children and any grandchildren by your daughters, and become a way to identify your female line descendants.4

A mutation a thousand years ago could link you to people far away, providing a clue to the origins of an ancestor. So if your interest is in tracing your own ancestry or the travels of the whole of humankind, mtDNA is a prime player. By testing the human populations of the globe, geneticists have been able to work out the order in which many of these mtDNA changes occurred. A phylogenetic tree has been constructed which leads back to a genetic Eve – the maternal ancestor of all living humans.5

In 1984 a momentous discovery was unveiled. Researchers at the University of California had succeeded in extracting mtDNA from a fragment of dried quagga muscle. What made this headline news was that the quagga (a member of the horse family) was extinct.6 Visions of resurrecting dinosaurs formed in the mind of science fiction author Michael Crichton. His novel Jurassic Park (1990) was adapted into the blockbuster film of the same name. Such terrifying experiments were a long way from the minds of geneticists. They were gripped by what ancient DNA (aDNA) could tell us about relationships between species, and indeed between people. Since there are so many more copies of mtDNA within the body than nuclear DNA, the chances of its survival after death are better. So early attempts to extract aDNA concentrated on mtDNA.

By the 1990s scientists were extracting DNA not just from preserved soft tissue, but also teeth and bones. Under favourable conditions, DNA can survive in remains for millennia. There was triumph when DNA was supposedly obtained from a 65-million-year-old dinosaur, until it was revealed to be human DNA. So much for Jurassic Park. The contamination of specimens by the DNA of those who have handled them turned out to be a major problem in this emerging field.7 Today it is recommended that newly discovered human remains should be excavated and handled only by persons wearing sterile gloves, face masks and coveralls [see 15], and that everyone involved in the manipulation and study of the remains should have his or her DNA tested to compare with the ancient specimens.8 Even so, contamination can creep in through the use of a standard biochemical technology.9 Fortunately, an array of new techniques, known as ‘next generation sequencing’, avoids this problem and has vastly increased the amount of DNA that can be extracted from extinct organisms.10 We now have the entire genome of the famous 5,300-year-old Alpine Iceman named Ötzi. We can work out that he had brown eyes, was lactose intolerant and at risk of heart disease. Infecting organisms can also be sequenced. Scientists found that Ötzi suffered from Lyme disease, transmitted to humans by the bite of infected ticks.11

Before results from ancient DNA could reach their present level of reliability, scientists were leaping joyfully to conclusions based on the DNA of living people. The eagerness with which some rushed to popularize and commercialize is understandable, but it is a prescription for confusion in this fast-moving field. Yesterday’s ideas may reach television viewers just as they are being overturned. Commercial genetic testing is precariously balanced on the cutting edge of science. Firms promising a certificate of Viking ancestry or descent from Niall of the Nine Hostages were jumping the gun. The science shifted before the ink was dry on the publicity material.

Worst of all was a tendency to circular thinking. Genetic results were interpreted in the light of a convenient archaeological model; then the conclusion was taken as proof of the model. Other studies selected a migration familiar from the history books and set out to find its genetic traces. Any genetic marker along the trail of the known migration was then linked to it. The hitch here is that many migrations took similar routes to earlier ones. Furthermore, the mass of migration in modern times has frequently muddied the tracks. Simple answers are in short supply.

Yet despite teething troubles, the nascent science of human population genetics is full of promise. Over the last few years papers and books have poured out in a whirling stream. Some overturn long-held ideas. Others support them. For those trying to get a grip on the story of Europe’s past, it has been the intellectual equivalent of white-water rafting: an exhilarating ride that leaves one breathless. Out of this seeming chaos a solid structure is emerging, piece by piece. Key publications have illuminated the great migrations in prehistory. Some are from archaeologists. Others are from population geneticists. Different strands of evidence are being knitted into a complex answer to that simple question: where did Europeans come from?

The restless peoples of Europe have stirred the gene pool many a time, overlaying the signatures of more ancient population movements. The resulting palimpsest cannot be read in an instant. The aim here is to give a taste of the convergence of evidence that may ultimately give us a clearer answer to the question. What emerges is that visions of stability must give way to a more dynamic view of Europe’s prehistory. The continent was not barred to incomers after the arrival of the earliest human beings. On the contrary, the tracks of Neolithic arrivals from the Near East can be seen in DNA. Nor were the Neolithic waves of migration the last ones of importance. Movements in the ages of metal had a massive impact, as did those after the fall of Rome.12

Europe is not a separate landmass. The idea that Europe and Asia are separate continents was perhaps the vision of early Mediterranean civilizations that had not penetrated far enough north to grasp the geography. Yet the idea of separate continents stuck. So a notional boundary had to be hit upon, which in antiquity was the Don River. Today it is the Ural Mountains.13 People have moved across that boundary, and across the Mediterranean, from time immemorial, so Europeans are closely related to their nearest neighbours.

Despite the high degree of genetic similarity among Europeans, there are still many places in the DNA code where one European might have a different sequence of bases from another European. By testing a huge array of these, it is possible to find national clusters.14 These clusters overlap across neighbouring countries, as we should expect. Modern political boundaries have little time depth. A Briton today with a strong sense of national identity may be astonished to find herself grouped with the French or the Irish, while a Portuguese may be disconcerted to fall among Spanish samples. Yet that counts as a pretty good match. On average a pair of modern Europeans living in neighbouring populations share around 10–50 genetic common ancestors from the last 1,500 years, and upwards of 500 genetic ancestors from the 1,000 years before that. There are marked regional variations within these figures. Sout...