![]()

CHAPTER 1 The Beginnings and Geometric Greece

There is no difficulty in tracing the development of the classical tradition in Western art from Greece of the 5th century BC, through Rome, the Renaissance, to the modern world. Working backwards, to its origins, the story is no less clear, but it is extraordinarily varied and there are two views about what should be regarded as its starting point. Once the Geometric art of Greece was recognized as Greek, the steps by which it was linked to the Classical period were quickly discovered. This was the work of scholars of the end of the 19th century, who were at last able to show that Classical art was not a sudden apparition, like Athena springing fully armed from the head of Zeus, nor a brilliant amalgam of the arts of Assyria and Egypt, but independently evolved by Greeks in Greece, and its course only superficially conditioned by the influence and instruction of other cultures, however important these had been in the preceding three hundred years.

But even while the importance of Geometric Greece was being recognized, excavators such as Schliemann and Evans were probing deeper into Greece’s past. The arts of Minoan Crete and of Mycenae had to be added to the sum of the achievements of peoples in Greek lands, and now that it has been proved that the Mycenaeans were themselves Greek-speakers the question naturally arises whether the origins of Classical Greek art are not to be sought yet further back, in the centuries which saw the supremacy of the Mycenaean cities.

The problem has been to find links across the Dark Ages which followed the violent overthrow of the Mycenaean world in the 12th century BC. It would be idle to pretend that there are none. There was continuity of race, and of language (although not writing) and craft continuity, albeit at a fairly low level. Moreover, the Dark Ages are now not so dark, and there were some stirring architectural achievements and indications of artistic activity at a high level though of foreign aspect already in the 11th century. But the fact remains that Mycenaean art, which is itself but a provincial version of the arts of the non-Greek Minoans, is utterly different, both at first sight and in many of its principles, to that of Geometric Greece. For this reason our story begins within the not-so-Dark Ages, with Greek artists working out afresh, and without the overwhelming incubus of the Minoan tradition to stifle them, art forms which satisfied their particular temperament, and out of which the classical tradition was to be born.

For this reason the only picture here of Bronze Age, Mycenaean Greece is probably the most familiar one – the Lion Gate at the main entrance to the castle at Mycenae [14]. There is more, however, than its familiarity which suggests its inclusion. It was one of various monuments of Mycenaean Greece which must have remained visible to Greeks in the classical period, beside massive walls which they attributed to the work of giants. And it illustrates two features of Mycenaean art which were not learnt from the Minoans, and which the Minoans had never appreciated. Firstly, the monumental quality of the architecture, colossal blocks and lintels piled fearlessly to make the stout castle walls which the life of Mycenaean royalty found necessary. Secondly, the monumental quality of the statuary, impressive here for its sheer size rather than anything else, since the forms derived directly from the Minoan tradition which was essentially miniaturist and decorative. More than five hundred years were to pass before Greek sculptors could command an idiom which would again satisfy these monumental aspirations in sculpture and architecture. It reminds us too that, from the earth, the new Greeks could recover and admire, if seldom imitate, other artefacts of their heroic past.

14 The Lion Gate at Mycenae. Two lions, their heads missing, stand at either side of an altar supporting a column. The triangular gap filled by the relief slab helps relieve the weight of the great lintel. 13th century BC

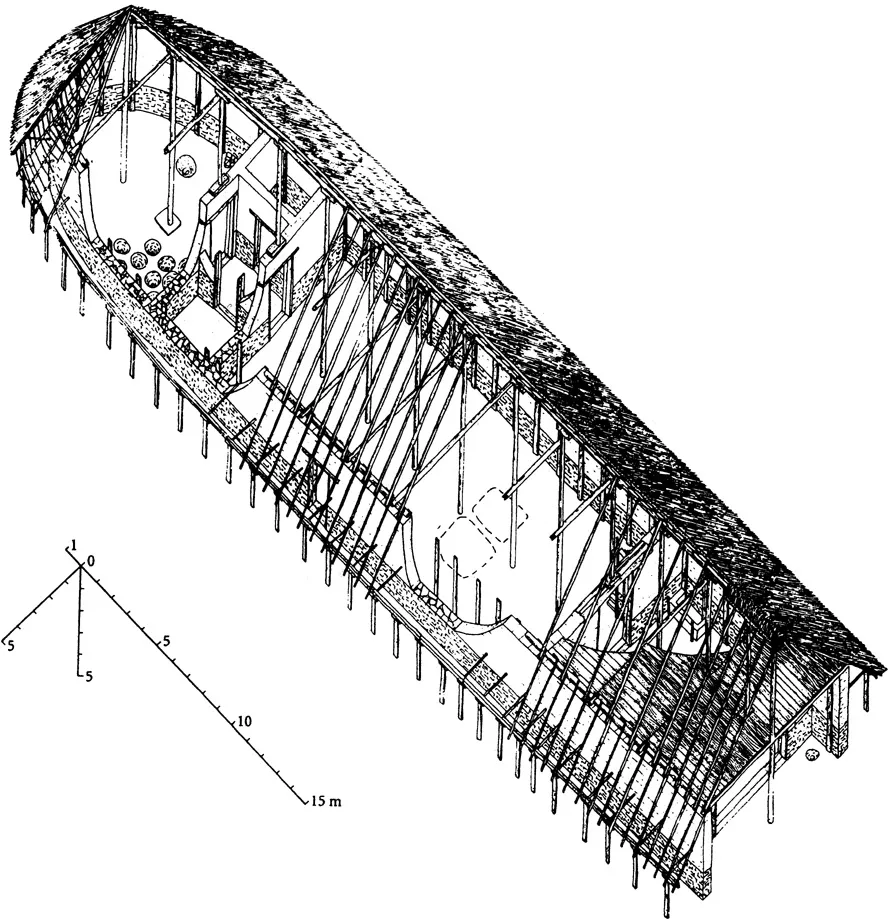

The architectural achievement of the Dark Ages is a discovery of recent years: a large apsidal building of brick and timber over stone, built around 1000 BC at Lefkandi, a port on the central Greek island of Euboea [15]. It contained two rich, indeed royal burials, equipped with foreign exotica, so it has as much the role of a hero-shrine as of a palace. The exotica, from the Levant and Egypt, are the harbingers of an Orientalizing revolution of which there will be more to say. The Euboeans were hardy seafarers and there is reason to believe that their importance in this period was due at least as much to their own eastern adventures as to prospecting foreigners. They were to have a pioneering role in colonizing the west later, but for a fuller assessment of Greek art of the 10th to 8th centuries and the rebirth of Greek art after the fall of the Mycenaean world we have to turn elsewhere. Thus, the strange clay centaur found in the Lefkandi cemetery [16] has Eastern and perhaps mythical associations that can still tax us.

15 Reconstruction by J.J. Coulton of the ‘heroon’ at Lefkandi. Its form is palatial, in a Greek tradition, but it was found to contain rich pit burials of a warrior, a woman and a four-horse team, and the whole was soon covered with a mound. About 1000 BC. 47+ × 10 m

16 Clay centaur from Lefkandi (head found in one tomb, body in another). The form has both earlier and eastern associations, notably with Cyprus. The man-horse is soon adopted by Greek artists and becomes their ‘centaur’. We do not know whether it was identified as such so early, but a nick in its leg corresponds with the story of the wounding of the senior centaur Chiron. About 900 BC. Height 36 cm. (Eretria)

Athens seems to have become important only at the end of the Bronze Age, but the city dominates the story of the Geometric period. To some degree its Acropolis citadel had survived the disasters attendant on the destruction of other Mycenaean centres, and her countryside was to serve as a refuge for other dispossessed Greeks. It is on her painted clay vases that we can best observe the change that takes place, and since a substantial number of the pictures illustrating this book will be of decorated pottery, nowadays a somewhat recherché art form, it will be as well to explain why this is. Virtually all that we know about the art of these early centuries has been won from the soil, and the rigours of survival have determined what our evidence can be. Virtually no textiles, leather or woodwork survive, for one thing; and only by good fortune marble or bronze, since they were only too readily appreciated by later generations as raw material for their lime kilns or furnaces. But a clay vase, with its painted decoration fired hard upon it, is almost indestructible. It can be broken, of course, but short of grinding the pieces to powder something will remain. In an age in which metal was expensive, and glass, cardboard and plastics unknown, clay vessels served more purposes than they do today, and in Greece at least the artist found on them a suitable field for the exercise of draughtsmanship.

On the vases made in Athens (and to a lesser degree in other areas of Greece, including Euboea) in the 10th century BC, we see the simplest of the Mycenaean patterns, arcs and circles, which are themselves debased floral motifs, translated into a new decorative form by the use of compasses and multiple comb-like brushes which rendered with a sharp precision the loosely hand-drawn patterns of the older style [17]. A few other simple Geometric patterns are admitted, but because we have yet to reach the full Geometric style of Greece, this period is called Protogeometric. The vases themselves are better made, better proportioned, and the painted decoration on neck or belly is skilfully suited to the simple, effective shapes. The painters had not forgotten how to produce the fine black gloss paint of the best Bronze Age vases, and as the Protogeometric style developed we see more of the surface of the vase covered by the black paint. The vases that survive come mostly from tombs and there is little enough to set beside them, except for simple bronze safety-pins (fibulae) and some primitive clay and bronze figures, especially from Crete [18] where, again, some of the Minoan forms and techniques seem to have survived.

17 A Protogeometric amphora from Athens, with the characteristic concentric semicircles on the shoulder and wavy lines at the belly. These belly-handled vases we...