eBook - ePub

Inside the Neolithic Mind

Consciousness, Cosmos and the Realm of the Gods

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Inside the Neolithic Mind

Consciousness, Cosmos and the Realm of the Gods

About this book

Drawing on the latest research, this brilliantly argued, elegantly written book examines belief, myth and society in the Neolithic period, arguably the most significant turning point in human history, when the society we know was born. Linking consciousness, imagery and belief systems the authors create a bridge to the thought-lives of the past.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Inside the Neolithic Mind by David Lewis-Williams,David Pearce in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

The Revolutionary Neolithic

A famous biblical town where trumpets brought the walls tumblin’ down introduces momentous themes (Fig. 1). The dramatic story of the Israelites’ capture of Jericho was sufficient to make the site famous, and biblical archaeologists have, naturally enough, been intensely interested in it. In contrast to their attempts to ‘prove’ the historical accuracy of the Bible, we turn our attention to much smaller finds than city walls and to what the site tells us about changes in human life.

The Bible relates that, when Joshua was about to lead the Israelites into the Promised Land, he prudently sent two undercover agents to ascertain the strength of Jericho, a strategic town positioned on an important trade route. His spies found that the settlement was fortified by high, strong walls. Early biblical archaeologists hoped to find proof of these walls and also of the sensational, divinely occasioned manner in which they fell:

And it came to pass on the seventh day, that they rose early about the dawning of the day, and compassed the city after the same manner seven times … Joshua said unto the people, Shout; for the Lord hath given you the city … So the people shouted when the priests blew with the trumpets: and it came to pass, when the people heard the sound of the trumpet, and the people shouted with a great shout, that the wall fell down flat … And they utterly destroyed all that was in the city, both man and woman, young and old, and ox, and sheep, and ass, with the edge of the sword. JOSHUA 6:15–16, 20–21

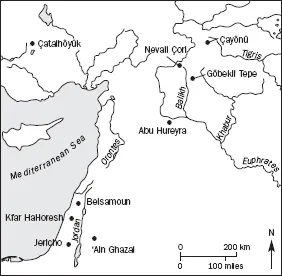

1 Map of the Near East showing places mentioned in the text.

Therein lies a dispute. An absence of skeletons of oxen, sheep and asses from the excavations suggested that the walls archaeologists eventually found were far older than the time of the Israelites’ occupation of the country: the level dated to a time before the domestication of animals. As with Heinrich Schliemann’s celebrated ‘discovery’ of Homeric Troy, there was not just one settlement, but the remains of a whole series of towns piled one on top of the other. It was hard to tell which layer was the one that the biblical archaeologists most wanted to find. The matter was settled with the advent of radiocarbon dating in the 1950s: the walls of Jericho are definitely too old to be the ones described in the Bible.

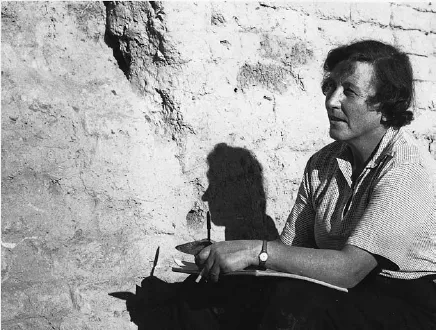

Today Jericho is closely associated with the name of the British archaeologist Dame Kathleen Kenyon (Fig. 2.) Her first season of excavation there was in 1952. She found a tell, or mound, that rises as much as 12 m (39 ft) above its surroundings; all in all, it covers about 25,000 sq. m (269,100 sq. ft). Pre-World War II archaeologists had sunk trenches and pits into the mound, but Kenyon’s own excavations were much more meticulous. She showed that the site had been initially occupied as long ago as 10,000–8500 BC by sedentary hunters and gatherers. Then, between 8500 and 7300 BC, domesticated plants appeared alongside bones of wild game, and the town burgeoned. At that time, 3.6-m (11.8-ft) high perimeter walls were built, as well as an impressive circular stone tower that rose to a height of 8 m (26.5 ft). Another innovation appeared a little later: between 7300 and 6000 BC, people began to keep domesticated sheep and goats. The appearance of plant and then animal domesticates at what was originally a hunter-gatherer settlement was evidence for the so-called ‘Neolithic Revolution’ (see below) at Jericho.

Half a century after Kenyon’s work, Jericho remains a key site in studies of the origins of farming. But some small finds there are even more astonishing than domesticates and city walls: in various ways, comparable discoveries run through the succeeding millennia of the Neolithic and suggest a kind of thinking that, at first glance, appears to lie outside of the ways in which people obtained their daily sustenance. To invoke a biblical trope, we may say that they show that people do not live by bread alone.

2 Dame Kathleen Kenyon: ‘The most remarkable manifestation of customs which can best be explained in terms of cult practices might be called a Cult of Skulls.’ 1

Skulls beneath the floor

In 1953 Kenyon noticed the top of a human skull protruding from the side of an excavated trench. She was at first reluctant to sanction its removal. She wished to abide by the rules of excavation that she herself had helped to make the cornerstone of archaeological work: the sides of trenches and pits must be kept sheer and clean so that diagrams of the stratification can be accurately drawn. Eventually, she ‘unwillingly’ gave permission for the removal of the skull. As she says,

Only the photograph … can convey any comprehension of our astonishment. What we had seen in the side of the trench had been the top of a human skull. But the whole of the rest of the skull had a covering of plaster, moulded in the form of features, with eyes inset with shells. What was more, two further similar plastered skulls were visible at the back of the hole from which the first had come. When these were removed, three more could be seen behind them, and eventually a seventh beyond.2

As often seems to happen in archaeology, the discovery was made at the end of a season’s digging. Nevertheless, plans to leave the camp were at once suspended, even though ‘the furniture had been all packed up, the kitchen cleared and the servants dismissed, the dark-room and repair room dismantled and most of the material packed up’.3 Kenyon and her colleagues continued their excavation, living ‘in considerable discomfort, sitting on the floor and eating picnic meals, while the photographer and repair assistant did wonders of improvisation’.4

As their work continued, they discovered that the skulls had been deliberately placed beneath the plaster floor of a house. It took five days to extract all seven of them. All had facial features – nose, mouth, ears and eyebrows – delicately modelled in clay, but the tops of the crania were left bare. One had its mandible in place; the rest had the missing jaw suggested by plaster fixed to the upper teeth. The interiors of the skulls were packed with solid clay. One specimen had bands of brown paint on the top of the skull, ‘perhaps indicating a head-dress’.5 In 1956, two more skulls were found beneath the same floor. It was a veritable charnel house (Pl. 7).

The plaster skulls enlarged on a pattern that had already come to light. Other houses had skeletons beneath their floors from which, in a significant number of instances, the skulls had been removed, apparently for further ritual treatment. Some severed skulls were in clear arrangements. In one case they were in a ‘closely packed circle, all looking inwards, in another arranged in three sets of three, all looking in the same direction’.6 In one find, there was ‘an unpleasant suggestion of infant sacrifice’ that seems to have jolted Kenyon: a collection of infant skulls still had the neck vertebrae in place, evidence that the heads were cut off and not merely taken from decayed burials.7

The Jericho skulls caused a sensation, but, since Kenyon’s excavations there, similar finds have been made elsewhere in the Near East. For instance, at ‘Ain Ghazal, an amazing site in Jordan (see Fig. 1), six plastered skulls were found. They were buried beneath house floors. In addition to the skulls, three ‘masks’ that had probably been attached to skulls were found in an outdoor pit dug especially for the purpose of receiving them.8

The Jericho skulls’ eyes were emphasized in a remarkable way. Six of the seven skulls had eyes

composed of two segments of shell, with a vertical slit between, which simulates the pupil. The seventh has eyes of cowrie shell, the horizontal opening of the shells gives him a somewhat sleepy appearance. The state of preservation of five was excellent, but the other two were less good, one having little more than the eyes surviving intact.9

These shells had been transported some 50 km (31 miles) from the Mediterranean. The eyes of the Jericho plastered skulls were considered important enough for these exotic, and no doubt prized, items to be placed in skulls that were probably displayed in some way but that were ultimately destined for a context in which they would no longer be seen – a grave. Why did they use shells in this way? Their smooth, white surfaces and their origin in a remote (for Neolithic people) sea are, we believe, features that have not received enough attention. The Jericho skulls show that, early in the Neolithic, eyes and ‘seeing’ were important and were in some way connected with death and, perhaps, the sea. We return to these points in Chapter 3.

These, then, are fleeting glimpses of themes that we follow up in subsequent chapters. They thread their way through what is arguably one of the most momentous times of human history: those few centuries when people began to domesticate plants and animals, and, at the same time, to develop complex belief systems that, seemingly, focused on the dead. The finds we have described give some initial insights into the Near Eastern Neolithic.

The Neolithic period

A few words have migrated from professional archaeological jargon to daily usage. ‘Palaeolithic’ is one, but it probably takes second place to ‘Neolithic’. Everyone has heard the word ‘Neolithic’, even if most people would be at a loss to define it. A few would know that it is concerned with the origin of farming and, as some writers more sensationally put it, the birth of civilization. But the less informed should not be overly concerned about their vagueness. Archaeologists, too, are still debating its exact meaning. Does it denote a period that can be fixed in time? Was it an event or a process? Does it imply a ‘package’ of features – farming would be one of them – that was adopted quite suddenly? Was the change to Neolithic life-ways a replay of a much earlier and, in western Europe, apparently comparably short time of innovation, the shift from the Middle to the Upper Palaeolithic?

That, much earlier, change-over in human history was characterized by the adoption of social and subsistence practices that have been labelled ‘modern human behaviour’. Until quite recently, this change was called ‘The creative explosion’10 and ‘The human revolution.’11 The suddenness with which new tool types, new hunting strategies, complex burials and, above all, art appeared in western Europe seemed to justify the use of ‘explosion’ and ‘revolution’. This burst of creativity was associated with populations of Homo sapiens who, some 30,000 to 40,000 years ago were living in western Europe side by side with anatomically more ancient groups of Homo neanderthalensis, famed Neanderthal Man.

Today, however, many researchers recognize that modern human behaviour emerged much earlier in Africa and was taken to western Europe, via the Near East, by Homo sapiens of the second ‘out of Africa’ migration.12 The African emergence of modern human behaviour was spasmodic: behaviours were adopted in some parts of the continent and not in others, and some may have been adopted and then later abandoned. When the two species of Homo came to live in proximity to one another in western Europe, conditions were ripe for an efflorescence of cave art and beautifully carved portable objets d’art (that is how we tend to see them today), as well as new tool types, new raw materials and new social structures; all these had been nascent in the communities of Homo sapiens as they moved out of Africa, through the Near East and across Europe towards France and the Iberian Peninsula.13

Overall, there was thus no ‘human revolution’ but rather a staggered process. In the special circumstances of western Europe 40,000 years ago, that process culminated in the illusion of a revolution: there was a comparatively sudden efflorescence of art and an acceleration of change in tool types and raw materials.

By contrast, for many decades of research, the suddenness of the appearance of the Neolithic at places like Jericho, at least compared with the aeons of economic stasis or very gradual change that preceded it, appeared quite clear. There seemed to have been a relatively swift change-over from foraging to agriculture, together with the new norms of ownership and property that must have accompanied it. This apparently swift change was emphasized by the archaeologist Gordon Childe when he memorably added the highly charged word ‘revolution’.14 The ‘Neolithic Revolution’ was for him one of the few great changes in mode of production (to use a Marxist term – Childe was a Marxist) that preceded the Industrial Revolution that, millennia later, ushered in the modern world with its manufacturing, surplus production, trade and commerce. The notion of revolution and why Childe favoured the term are points that deserve attention because he influentially discussed the questions that are asked in most of our subsequent chapters: What generates changes in societies? Why did people domesticate plants and animals? Why did they make plastered skulls and other ritual objects?

A child of Marx

Vere Gordon Childe, probably the most written about of all archaeologists, was born in Australia in 1892. After taking his first degree at the University of Sydney, he studied classical philology at Oxford University. In the aftermath of World War I, he became involved in Australian left-wing politics and thus consciously forged a link between his own political philosophy and archaeological research. After a spell as Professor of Prehistoric Archaeology at the University of Edinburgh, Childe became Director of the Institute of Archaeology at London University, a post that he held until his retirement in 1956. He returned to Australia where, the following year, he died, apparently by his own hand. His body was found at the foot of a cliff in a part of Australia that he loved. He left a legacy of highly stimulating books that are still required reading for archaeologists.

The Left, following in Marx’s and Engels’ footsteps, had its own ideas of social change and human history. As a consequence of his reading of Marxist theory, Childe came to see social change as revolutionary. History was punctuated by social upheavals that resulted from class struggles: ‘The history of all existing society is the history of class struggles.’15 A small ruling elite appropriates the ‘social surplus’ that the lower orders of society produce, and this state of affairs lasts until, suddenly, the social relations that support the production of th...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- About the Authors

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 The Revolutionary Neolithic

- 2 The Consciousness Contract

- 3 Seeing and Building a Cosmos

- 4 Close Encounters with a Built Cosmos

- 5 Domesticating Wild Nature

- 6 Treasure the Dream Whatever the Terror

- 7 The Mound in the Dark Grove

- 8 Brú na Bóinne

- 9 Religion de Profundis

- 10 East is East and West is West

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgments

- Sources of Illustrations

- Colour Plates

- Copyright