- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The art created in the caves of western Europe in the Ice Age provokes awe and wonder. What do these symbols on the walls of Lascaux and Altamira, tell us about the nature of ancestral minds? How did these images spring into the human story? This book, a masterful piece of detective work, puts forward the most plausible explanation yet.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Mind in the Cave by David Lewis-Williams in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER I

Discovering Human Antiquity

The questions raised by Time-Byte I are the principal subject of this book. Why did the person of 13,000 and more years ago undertake such a hazardous journey? What emotions did he experience? Was the person a man, as we so easily assume, or was it a woman? How old was the person? Why did he or she believe it was important to place the bear tooth in the wall of the cave? It was not the only object placed in the cave walls: there are also pieces of bone, stone tools and core-stones.2 What did he or she believe about the images on the walls? What did the subterranean journey ‘do’ for him or her?

These questions are not just about ancient history. They take us to the heart of what it is to be human today. It is not simply that we are more intelligent than other creatures, that we are masters of complex technology, or even that we have complex language. These are glittering jewels in the crown of humanity with which we are comfortable. On the contrary, the essence of being human is an uncomfortable duality of ‘rational’ technology and ‘irrational’ belief. We are still a species in transition. The unknown person of Time-Byte I had the rational, ‘scientific’ knowledge and skill to make a tallow lamp and also a set of beliefs that were the imperative for his or her apparently irrational underground journey. That duality in human behaviour did not disappear at the end of the Stone Age. Even in the twentieth century, people were ‘rational’ enough to travel to the moon and back and yet still ‘irrational’ enough to believe in supernatural entities and forces that transcend, and in effect make nonsense of, all the laws of physics on which their moon journey depended. Does the human brain construct spaceships and the human mind fashion unseen forces and spirits? What is the difference between brain and mind? What is intelligence and what is human consciousness? How did early people reach a stage of evolution that allowed them to make and understand pictures? These are just some of the issues with which we shall have to grapple when we try to answer the questions posed by Time-Byte I.

What the seventeenth-century people of Time-Byte II thought the images in Niaux were or who they thought made them we do not know. Perhaps Ruben de la Vialle and others who had been there before him believed that the pictures had been made by recent visitors like himself, and so he added a contribution of his own – his name and the date. At that time, Western thought had no concept of prehistory; the received view was that the world had been created by God. According to Archbishop James Ussher (1581–1656), this miraculous event occurred in 4004 BC. Later, Bishop John Lightfoot refined Ussher’s calculations and announced that creation took place at nine o’clock on the morning of 23 October 4004 BC. Not everyone, even at that time, may have accepted the happy fortuity of creation coinciding so neatly with the beginning of the Cambridge University academic year, but virtually everyone believed that human history started miraculously at a moment that was not so very long ago. De la Vialle had no conceptual framework into which to fit the significance of what he was seeing, so, in effect, he did not ‘see’ it at all.

What happened during the years between Time-Byte II and Time-Byte III? Why did Jean-Marie Chauvet and his friends see what de la Vialle missed? The answer is both simple and momentous. The Western world had learned that it had a deep past, its concept of humanity had undergone profound changes, and its yearning to know the truth about its origins had risen to a level of unprecedented intensity: finding evidence for ‘Human Origins’, be it stone artefacts, fossils or genes, had become an absorbing passion. The chasm created by the passing of, not merely Archbishop Ussher’s 6,000 or so, but 30,000 years, suddenly closed. As Chauvet himself wrote, ‘Time was abolished.’ Despite the enormous time gap, he and his friends felt as if they could sense the ‘souls and spirits’ of the artists surrounding them; the hidden images invoked not only ‘scientific wonder’ but also awe and ‘spiritual’ proclivities. They used words like ‘artists’ and ‘masterpieces’. They were identifying with people whom they took to be their remote ancestors. Shared consciousness, they believed, was a bridge to those ancestors. They were right, though perhaps not in a way that they would have recognized.

A revolution in Western thought

The story of the sea-change in Western thought that took place between Time-Bytes II and III began in the first half of the nineteenth century. At that time, the influence of writers such as Sir Charles Lyell (1797–1875) was beginning to be felt. Lyell, Professor of Geology at King’s College, London, published his immensely important Principles of Geology in 1830. He argued that layered sedimentary rocks and the fossils they contain point to an antiquity of the earth until then unsuspected. At first, conservative fundamentalist Christians, and not a few geologists, accommodated the fossils by suggesting that they came from a barbaric antediluvian period. For them, the fossils simply confirmed the historical accuracy of the Biblical account of the catastrophic flood that Noah and his family survived. The Church championed this idea because it fitted well with the Biblical record. Given the short span of time allowed for human history, catastrophes had to be invoked, and so-called Diluvialists debated not just Noah’s flood but also the number of pre-Noachian floods.

Lyell, however, firmly rejected catastrophism of this kind and argued instead for the operation of gradual processes – the same erosional, depositional, volcanic, faulting and folding processes that are evident today sculpted the earth from the beginning. This idea was enshrined in the lengthy title of his great work: Principles of Geology, Being an Attempt to Explain the Former Changes of the Earth’s Surface by Reference to Causes Now in Action. Lyell later allowed that the intensity of change may have varied, but the notion of uniformitarianism was born: at least in geological terms, the past was no different from the present, and the fossil record showed that a lot happened before 4004 BC. Immediately, the battle lines were drawn.

Yet, despite conservative resistance, the old way of seeing human history was beginning to crumble. The notion of slow evolutionary change was in the air. Sensationally, an anonymous evolutionary tract appeared in 1844; it was entitled Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation. Much later, the author turned out to be Robert Chambers, who had worked for Sir Walter Scott and who eventually, with his brother William, founded the Edinburgh publishing house W. & R. Chambers. Vestiges outlined the history of the world from a gaseous cloud, through the fossil record and up to the transmutation of apes into human beings. Chambers, privately a sceptic, nevertheless insisted on the presence of God and believed in phrenology and spiritualism. Still, many readers considered the book to be dangerously atheistic. What Chambers’s scheme really lacked was a mechanism that would account for the transformations that he described. That key was supplied by a far more rigorous thinker.

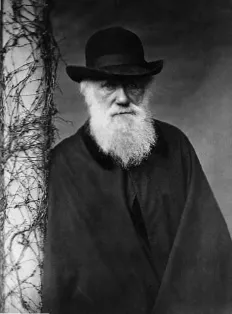

Charles Robert Darwin (1809–82), who as a young man had circumnavigated the globe and studied a broad range of botanical and zoological topics, was the catalyst (Fig. 4). Darwin set out on that voyage holding the view that the world had indeed been created by God and that species were separate creations. He began to sharpen his more scientific ideas in debates with the captain of the Beagle, Robert Fitzroy, a fanatical proselytizer, but at that time Darwin had enough in common with him to publish a jointly authored article in the South African Christian Recorder in 1836.3 The article was a plea for more missionaries to be sent to the Pacific. Darwin’s easy relationship with Fitzroy was, however, doomed.

Before long Darwin realized that what was missing from biological thought was a persuasive account of the mechanism of change: how could one species evolve into another? As early as 1844, he prepared an article that encapsulated the main tenet of his answer to this question – natural selection. But he did not publish his work; he showed it only to a friend, the celebrated botanist Joseph Hooker. After 1844 Darwin continued to collect data to support his theory. As part of this work he produced a highly detailed and definitive study of barnacles. It contains no mention of his ideas on evolution.

Darwin’s theory of evolution did not come to him fully formed as he stood on the shores of the Galapagos Islands. Rather, his conversion proceeded gradually and in close co-operation with numerous celebrated specialists in taxonomy and systematics. But it was he, not they, who perceived the wood and not just a scatter of trees. At the beginning of his work, he was as prejudiced against evolutionary ideas as they, but something in his make-up, some hard-to-define ‘genius in science’, allowed him to see connections that escaped the meticulous inspection of others.4

Then came a decisive moment. On 18 June 1858, Darwin received an essay from Alfred Russel Wallace (1823–1913), a naturalist who was then 12,000 miles away in the Moluccas Islands. Wallace’s essay was entitled On the Tendencies of Varieties to Depart Indefinitely from the Original Type. Darwin’s previous correspondence with Wallace had not prepared him for the content of the article. For Darwin, it was ‘a bolt from the blue’. He realized that Wallace’s ideas about how species changed and evolved into other species were very similar, even identical, to those on which he had been brooding for so long.Wallace, he feared, was about to seize the initiative, but, being a man of great magnanimity, he did not wish to deprive him of his due. At once, Darwin consulted Lyell, who, ever active and influential in such matters, facilitated the reading of papers on natural selection by both Darwin and Wallace at the Linnean Society in London. The occasion was scheduled for 1 July of the same year.

4 Charles Darwin, catalyst of modern thought. It was his penetrating insights into the mechanism of evolution that made a modern, rational assessment of prehistory possible.

In the event, the papers were read not by the authors but by the secretary of the Society: Darwin, as became his habit, remained at home, and Wallace was in the Moluccas. Surprisingly, few of those present seem to have found the occasion especially noteworthy. Perhaps the secretary’s delivery was soporific. The President recorded in his annual report that the papers did not deal with one of those ‘striking discoveries which at once revolutionize, so to speak, the department of science on which they bear’.5 This stunningly banal evaluation of the explosive material contained in the two papers says something about the unpredictable nature of the receptivity of ‘scientific’ minds. A more decisive blow needed to be struck.

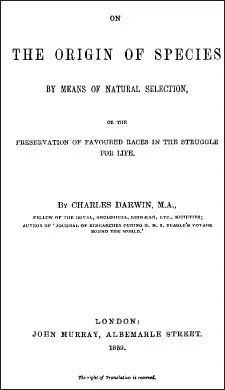

It came in 1859 with the publication of Darwin’s hastily completed, but as always meticulous and erudite, book On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection (Fig. 5). Despite its more than 400 pages, Darwin regarded it as an ‘abstract’.6 He subtitled it The Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life, and the popular phrase ‘survival of the fittest’ became part of Western thought – together with a series of attendant racist notions of which Darwin would certainly not have approved. The actual phrase, ‘survival of the fittest’, was first used by the English philosopher Herbert Spencer in 1865, and Darwin acknowledged it in the 1869 edition of On the Origin of Species. Darwin himself neatly summed up his central idea thus: ‘…the theory of descent with modification through natural selection’.7 The first printing of 1,250 copies of On the Origin of Species was sold out on the first day, an achievement that few, if any, subsequent scientific writers have been able to equal. By 1872, six editions and 24,000 copies had been published; by 1876, the book had been translated into every European language. Here was the conceptual framework that de la Vialle lacked, a framework that opened up an entirely new perspective on humanity. Suddenly, Westerners who had access to Darwin’s ideas could ‘see’ things that they had never noticed before.

The most famous public clash came in 1860 at an Oxford meeting of the British Association. Darwin was again not present. Expectation was running high because it was common knowledge that the Church, as embodied in Bishop Samuel Wilberforce, was, as the Bishop himself said, about to ‘smash Darwin’. The event exceeded even the noisy students’ hopes. In one of science’s most in famous foolishnesses, Wilberforce asked Thomas Henry Huxley if it was through his grandmother or his grandfather that he was descended from an ape.

5 The book that changed the world: the title page of the first edition of On the Origin of Species. It became the foundation of modern thought and philosophy.

Huxley (1825–1895), trained as a surgeon, was at that time Professor of Natural History at the Royal School of Mines; he was a popular lecturer who was able to make abstruse matters plain to ordinary people. He coined the word ‘agnostic’ to describe his own position on religious issues and was happy to call himself ‘Darwin’s watchdog’. When the absurdly facetious question was put to him he was heard to murmur, ‘The Lord hath delivered him into mine hands.’ When he rose to reply to the Bishop, Huxley said that he would rather be descended from an ape than from a bishop who prostituted the gifts of culture and eloquence in the service of falsehood. At once there was an uproar. The students loved it, but Fitzroy, the Beagle’s former captain who happened to be present, was heard to yell above the hubbub that he had warned the young Darwin about his dangerous thoughts. The rest of his words were drowned by the tumult. Less than five years later, overwhelmed by religious despair, Fitzroy took his own life.

The following year, also in Oxford, Benjamin Disraeli coined an enduring phrase.8 First, he asked, ‘What is the question now placed before society with a glib assurance the most astounding? The question is this – Is man an ape or an angel?’ His response to his own question turned out to be memorable: ‘My Lord, I am on the side of the angels.’

In his epoch-making book, Darwin skated around the implications of his theory for human evolution, though he did say briefly that the theory of evolution by natural selection would throw light on ‘the origin of man and his history’, and that psychology will show ‘the necessary acquirement of each mental power and capacity by gradation’.9 His circumspection was prudent because, at that time, there was virtually no fossil evidence for human evolution. Nevertheless, this was a topic to which he turned in his 1871 book, The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. He did not shy away from the profound implications of ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- About the Author

- Contents

- Preface

- Three Caves: Three Time-Bytes

- 1 Discovering Human Antiquity

- 2 Seeking Answers

- 3 A Creative Illusion

- 4 The Matter of the Mind

- 5 Case Study 1: Southern African San Rock Art

- 6 Case Study 2: North American Rock Art

- 7 An Origin of Image-Making

- 8 The Cave in the Mind

- 9 Cave and Community

- 10 Cave and Conflict

- Envoi

- Notes

- Bibliography and Guide to Further Reading

- Acknowledgments

- Sources of Illustrations

- Colour Plates

- Copyright