![]()

The_Sick_Rose_1_256.indd 2 10/01/2014 14:0

![]()

![]()

![]()

The_Sick_Rose_1_256.indd 5 10/01/2014 14:0

![]()

The_Sick_Rose_1_256.indd 6 10/01/2014 14:0

![]()

The_Sick_Rose_1_256.indd 7 10/01/2014 14:0

![]()

The_Sick_Rose_1_256.indd 8 10/01/2014 14:0

![]()

The_Sick_Rose_1_256.indd 9 10/01/2014 14:0

![]()

The_Sick_Rose_1_256.indd 10 10/01/2014 14:0

![]()

The_Sick_Rose_1_256.indd 11 10/01/2014 14:0

![]()

The_Sick_Rose_1_256.indd 12 10/01/2014 14:0

![]()

The_Sick_Rose_1_256.indd 13 10/01/2014 14:0

![]()

The_Sick_Rose_1_256.indd 14 10/01/2014 14:0

![]()

The_Sick_Rose_1_256.indd 15 10/01/2014 14:0

![]()

The_Sick_Rose_1_256.indd 16 10/01/2014 14:0

![]()

The_Sick_Rose_1_256.indd 17 10/01/2014 14:0

![]()

The_Sick_Rose_1_256.indd 18 10/01/2014 14:0

![]()

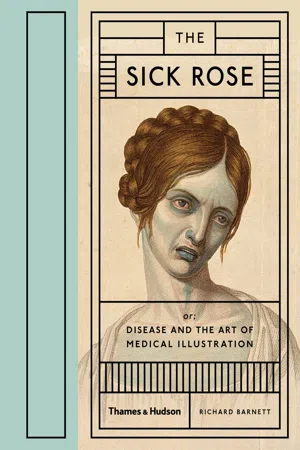

COnTEnT S I n T RO D U C T I O n Disenchanted Flesh 20 I II SK I n D I S E A S E S lE PROSy III S M A llP O x Iv TU B E RC U lOS I S v vI CH O lE R A C A nC E R vII H E A RT D I S E A S E vIII v E n E R E Al D I S E A S E S Ix PA R A S I T E S x g O U T O P P O S I T E | various pathological processes and infections thought to result in the accumulation or release of pus. The Boundary of the Body 42 More than Skin Deep 72 Blistered by Act of Parliament 94 The White Death 110 A Free Trade in Disease 128 The Claws of the Crab 144 Crowns and Murmurs 164 A lifetime with Mercury 180 Colonizers Colonized 214 Fashionable Agony 232 F U RT H E R R E A D I n g Pl AC E S O F I n T E R E ST 244 246 SO U RC E S O F I llU ST R AT I O n S 248 252 256 AC Kn OW lE Dg M E n T S I n D E x The_Sick_Rose_1_256.indd 19 10/01/2014 14:0

![]()

DISEnCHAnTED FlESH MEDICInE AnD ART In An A gE OF REv OlUTIOn The English essayist William Hazlitt died in poverty in 1830, just as European physicians were beginning to experiment with the first achromatic microscopes, and a few years after the French inventor nicéphore niépce had made the first permanent photo-etching. As a young man Hazlitt had trained as a painter, and in his writings – still some of the finest prose in the language – he returned again and again to the question of truth in representation. How should an artist depict the flesh and the soul, and what thoughts and feelings should such a depiction evoke? In ‘On Imitation’, published in The Examiner in 1817, he turned his own penetratinggaze to the subject of anatomical illustration: The_Sick_Rose_1_256.indd 20 10/01/2014 14:0

![]()

‘thE anatoMist is DElightED With a ColourED platE, ConvEying thE Exa Ct appEaranCE oF thE progrEss oF CErtain DisEasEs, or oF thE intErnal parts anD DissECtions oF thE huMan BoDy. WE havE knoWn a JEnnErian proFEssor as MuCh EnrapturED With a DElinEation oF thE DiFFErEnt stagEs oF vaCCination, as a Florist With a BED oF tulips, or an auCtionEEr With a CollECtion oF inDian shElls.... thE lEarnED aMatEur is struCk With thE BEauty oF thE Coats oF thE stoMaCh laiD BarE, or ContEMplatEs With EagEr Curiosity thE transvErsE sECtion oF thE Brain…anD ovErCoMEs thE sEnsE oF pain anD rEpugnanCE , WhiCh is thE only FEEling that thE sight oF a DEaD anD ManglED BoDy prEsEnts to orDinary MEn. it is thE saME in art as in sCiEnCE .' But how should we understand this tension between ‘the beauty of the coats of the stomach’ and ‘the sight of a dead and mangled body’? Should we seek to resolve or ‘overcome’ it, or should we practise what Hazlitt’s admirer, the medical-student-turned poet John Keats, called negative capability – the capacity to be ‘in uncer tainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason’? The images in this volume embody one kind of answer to this question. This book is about a revolution in the ways that Western medical practitioners have seen the human body, and the ways in which they have known disease. In the hundred years or so in which these images were made – from the last decade of the eighteenth century to the first decade of the twentieth – Western medicine began a conversation with modernity in many forms: science, technology, industrial society, urban life, mechanized warfare, the long shadow of imperialism. In doing so it decisively abandoned an ancient consensus about the structure of the body and the meaning of disease. For elite Classical, Renaissance and Enlightenment medicine, health was a balanced constitution composed offour humours. A surfeit or insufficiency of blood, black bile, yellow bile, or phlegm lay at the root of all diseases. Physicians – learned, humane, attuned to all the failings of the flesh – would negotiate a diagnosis and a course of treatment with their genteel or aristocratic patient- masters. Surgeons, the carpenters of the body, would be on hand to carry out messy and painful physical interventions. Blood might be let, bile might be purged, a change of air or diet might be advised, but most of all physician and patie nt would watc h and wait. Interrupting the natural course of a disease, trying to outstrip the body’s own powers of healing, might itself be fatal. The_Sick_Rose_1_256.indd 21 10/01/2014 14:0

![]()

A little more than a century later, on the eve of World War I, medicine was for most (though not all) of its practitioners no longer a learned art. Physicians and surgeons had signed up to an uneasy covenant with the new sciences of physiology and bacteriology. In learning the disciplines of the laboratory and the microscope they entered a strange, compelling world, one in which localized physical lesions or invasions of bacteria disrupted tissues composed of cells. To borrow a word from the sociologist Max Weber, this new world was founded in a vision of the body ‘disenchanted'. no timeless mysteries, only temporary ignorance; no vital force or soul, only an endless dance of enzymes and substrates. In a century obsessed with, even haunted by the possibility of progress, the practitioners of scientific medicine offered themselves as the shock troops of the future perfect. This book follows a single strand of the Western medical tradition – illustration of the diseased human body – through this jarring encounter with modernity. like their prede cessors, nineteenth-century physicians, surgeons and anatomists built close relationships with artists, craftsmen and publishers. The images that emerged from these collaborations are beautiful and morbid, sublime and singular. They are icons of a certain kind of clinical objectivity, but their aura of objectivity is the result of countless human interventions, conscious and unconscious. They give us, so to speak, the outside of the inside; they are insistently concerned with surfaces, but surfaces that in life and health are never seen. These images can seem to epitomize progress in a century of light, but they also carry an ineradicable whiff of the morgue, of the exercise of state power over paupers and criminals, of the body violated, of nakedness revealed. They are founded in the practices of dissection, and they are parasitic upon the dead, sometimes the body-snatched or executed. They present an uncanny spectacle of the dead body articulated: not only prepared and mounted for display, but also made to speak (in a voice that is not wholly their own). Most of all they instantiate a revolutionary concept of clinical authority – one rooted in the dead patient’s body rather than the living patient’s voice. The_Sick_Rose_1_256.indd 22 10/01/2014 14:0

![]()

THE THEATRE OF An ATOMy At some point in the late thirteenth or early fourteenth century, in the school of arts and medicine at the University of Bologna, anatomists began to open up dead human bodies before an audience of scholars. They worked, metaphorically speaking, with a knife in one hand and a treatise in the other. This resurgence of systematic anatomy ran in parallel with the translation of anatomical texts by the Roman physician and surgeon Claudius galen. Appropriately enough for a movement that mingled Classical philosophy with Catholic theology, Renaissance anatomy drew inspiration from three axioms, two pagan and one Christian. The Book of genesis taught that man was created in the image of god; the greek philosopher Protagoras maintained that man was the measure of all things; and a Classical proverb urged all men to ‘know thyself’. galen’s re-workings of Hippocratic humoral theory were taken up in texts like the influential Anathomia corporis humani (1316) by the Bolognan anatomist Mondino de’luzzi, and for more than four centuries they served as the theoretical backbone of Western medical thought. For a later generation, notably the Brussels-born peripatetic Andreas vesalius, galen’s injunction that all anatomists should make their own observations led them to challenge his own descriptions of human anatomy (which seem to have been taken from studies of apes and pigs). In his De Humani Corporis Fabrica (1543) vesalius depicted his own dissections of executed criminals in Padua and Bologna, crafting what he saw as a heavily corrected and far more detailed revision of galen’s anatomical morphology. Over the next century, anatomists such as the Italian Hieronymus Fabricius and his English pupil William Harvey overturned many more of galen’s precepts – most famously Harvey’s demonstration in De Motu Cordis (1628) that blood was not made in the liver, but pumped around the body by the heart. The_Sick_Rose_1_256.indd 23 10/01/2014 14:0

![]()

Though the broad principles of Hippocratic humoralism continued to dominate medical thought, seventeenth-century natural philosophers began to undermine Classically derived notions about the deep structure of the body and its place in the order of things. In different ways René Descartes, Thomas Hobbes and Isaac newton each recast the universe as a space in which matter moved and interacted according to universal laws. The fundamental components of life might not be humours but particles, and the body might be refigured materialistically as a machine, a matrix of pipes, pumps and levers. In a mechanistic cosmos physicians and surgeons were more like clockmakers or mechanics, repairing broken joints and replacing worn-out cogs. This medical materialism chimed with wider currents in Western culture, usually drawn together under the rubric of the Enlightenment. The ideology of the Enlightenment, set out in works by writers such as John locke, David Hume and the Marquis de Condorcet, was threefold. It was rational, seeking to place learning, society and government on a sound footing of reason. It was empirical, making and testing knowledge through observation and the senses, rather than mere theorizing. And it was genteel, proposing education and conversation, rather than repression and violence, as the tools for running societies. Most of all, it raised the tantalizing possibility that people and cultures could progress, enjoying more freedoms, better health and longer lives. This stirring rhetoric must be set against the harsher and more compromised realities of eighteenth-century culture and politics, not least the continuing European involvement in slavery. But anatomy, surgery and medicine became tied up with politics and philosophy, in the construction of a new ‘science of man’ as the basis for an enlightened society. The_Sick_Rose_1_256.indd 24 10/01/2014 14:0

![]()

Under these influences medicine began to move away from the humoral holism of Hippocratic thought, coming instea...