![]()

CHAPTER 1

An Afternoon in Florence

In June 2012 we met in a city so crammed with art that its very name is a byword for pictures and sculpture. To visit Florence without visiting churches and museums would be perverse. It is also a place where you can experience the first morphing into the second: site of worship into temple of art appreciation. Our very first port of call was not a fragment but a whole: a cycle of great pictures that was still on the walls on which it was painted over half a millennium ago.

Philippe was staying in Florence for a few days while he was speaking at a conference, and I flew over to join him. My hotel was in Oltrarno – the district on the south bank of the Arno. As soon as I arrived, we met, ate lunch, and went straight through the hot, almost deserted, streets to the Brancacci Chapel in the church of Santa Maria del Carmine. We bought our tickets and found – astonishingly – that we had the place to ourselves.

PdM It is, like so much of what we see, a visual palimpsest. That is, a series of images and interventions placed side by side, or superimposed, through time.

Masaccio and Filippino Lippi, Raising of the Son of Theophilus and St Peter Enthroned detail (right hand side), 1425–27 and c. 1481–85. Fresco. Brancacci Chapel, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence.

The chapel was built by Pietro Brancacci around 1386; almost forty years later the fresco decoration was probably commissioned by his nephew from Masolino, who worked with his younger associate, Masaccio. The frescoes were left unfinished until the end of the 15th century, when the cycle was completed and parts altered by a third great painter, Filippino Lippi. It has been a shrine of art almost as long as it has been a place of worship. The young Michelangelo came here to copy Masaccio’s frescoes and thus learn how to draw.

Subsequently, the church experienced both disasters and transformations, including a fire and an architectural remodelling in the late 18th century. The frescoes were cleaned and restored in the late 20th century. But still we felt, when we stepped into the chapel itself, that we were entering a time capsule: a room of 15th-century pictures.

PdM The key is that we are stepping into that era. You realize here what museums simply cannot do, which is to put you within the frame, almost within the world and the time of the artist. Of course, one can never re-enter the past, that moment has gone. But this is as close as one can ever get. In this chapel, everything leads one into it – above all the corporeal reality of Masaccio’s figures. Their sense of weight and presence must have caused amazement at the time. Already they show such key elements of Renaissance art as gravity, seriousness and moral authority. They display an assertiveness and a calm severity that reflects the city’s growing self-confidence.

From the Brancacci Chapel, we proceeded back across the Arno to the eastern quarter of the city, to the basilica of Santa Croce. It is a huge church, begun at the very end of the 13th century for the Franciscan order, but only completed in the mid-15th, with some alterations carried on in the late 16th by Giorgio Vasari, painter, architect and, through his Lives of the Artists, the grandfather of modern art history. The façade was added in the 19th century.

Santa Croce remains a church, but quite early on it began to change into something else: a pantheon, the place of burial of famous Florentines, and by the 19th century a Valhalla of celebrated Italians. The tomb of Michelangelo is to be found here, also those of Galileo, Machiavelli and Rossini. Because of the artists who carried out decorations in the basilica, it soon took on another character.

The building became an assembly of great works of art, in other words, a sacred space transformed for art lovers into a museum. It seemed quite appropriate, therefore, that we had to queue at a ticket office before going in, as if we were at the Louvre or the Met. Already in the 1490s, the young Michelangelo also studied here, copying the frescoes by Giotto in the Peruzzi and Bardi Chapels. In the basilica are to be found works in painting, sculpture and architecture that, taken together, are a sort of early canon of Florentine art: works by Giotto, Brunelleschi, Donatello and many others. But there is one difference between Santa Croce and any actual museum: all the works here were made to go in this place.

PdM We are in front of Desiderio da Settignano’s tomb of Carlo Marsuppini, the chancellor of Florence and early humanist. Its wonderfully light sarcophagus, decorated with acanthus leaves, seems almost to be taking flight, lifted by a winged scallop shell that has been interpreted as symbolizing the journey from life into death and ultimately into the spiritual realm. On either side stand two delightful and slightly impish putti with shields, keeping guard.

The sarcophagus itself is a great work of sculpture. How often in this museum age are you confronted with the ‘architecture’ of a sculptural ensemble in this way – the narrative as one unblemished whole, with all its parts, painted and sculpted?

Once again it reminds us how, in museums, we admire what are often fragments from larger ensembles. If one of these putti were pinioned on a pedestal in the Met or the Louvre we would still admire it; just the label would alert us to its original role as one small component of a much larger composition. But only in seeing the whole do you understand the relationship of the parts: how the stances of the putti relate to each other, their glance cognisant of the gisant – the effigy of Marsuppini. In its proper place, it is all so much more rich and, indeed, authentic.

Tomb of Carlo Marsuppini (1399–1453), Chancellor of the Florentine Republic, by Desiderio da Settignano. Marble, c. 1453. Basilica of Santa Croce, Florence. Universal Images Group/SuperStock.

MG It would lose something even if you extracted all the stones from the wall and took them to a museum.

PdM Exactly. Because the tomb was conceived to be set into the architecture of the church, of which it then became an integral part. Space, scale, acoustics even, and of course light, are all vital elements that would be lost if the ensemble was transferred to another place. That’s the wonder of being here, in the strict sense. I say this because the church itself is now a museum, or functions as one, but a museum for which the works on view were originally intended and conceived.

Though not a part of a single decorative programme, the interior of Santa Croce is filled with accretions from many different periods and styles – layered history in full view. Sometimes what we see has been revealed by restorers, such as the Giotto frescoes that had been whitewashed over.

There are two chapels containing frescoes by Giotto, dating to c. 1320–25, but they are very dissimilar in condition. Both were discovered under white-wash in the 19th century, but they have been dealt with very differently by time.

The frescoes in the Bardi Chapel were painted in buon fresco, which bonds chemically with the plaster and, if the conditions are right, lasts very well. The frescoes by Giotto in this chapel have indeed lasted extremely well, except for those areas where tombs and monuments were inserted into the walls. Now what we see are areas of masterly painting by Giotto, interspersed and interrupted by the shapes of baroque arches and funerary structures, since removed.

The Peruzzi Chapel next door had a quite different fate due to the technique Giotto employed. He painted this cycle not in buon fresco but a secco – that is, he painted over the dry plaster so the paint did not bond, and it has become rubbed and blurred over time. Recent analysis suggests that the original effect was as rich as panel painting.

PdM Here, we are very conscious of what we are missing. Originally, the colours would have been brighter, making the narrative much clearer and more powerful. Now, the effect is a bit like looking at a faded tapestry. If you look at the back of a tapestry, the difference in the vividness of colour between the front that has been exposed to light and the back is dramatic. The number of tapestries that are now totally washed out and thereby ruined is heartbreaking. If you could, you’d hang them wrong side out. When you compare the murals in the Peruzzi to those in the Bardi Chapel next door, you see how, through fading, time has diminished the impact of the fresco.

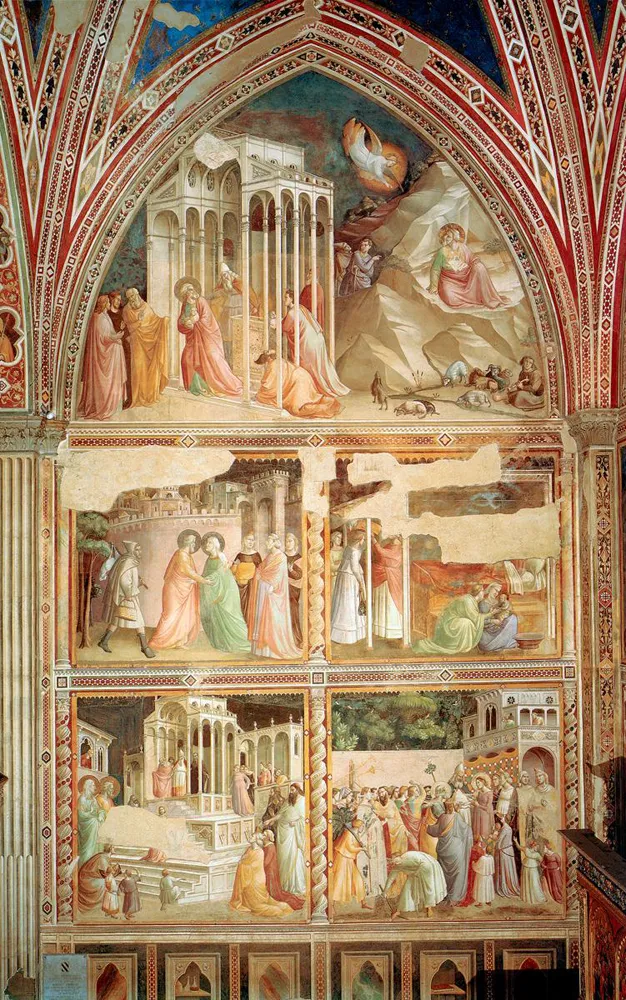

We moved on to the Baroncelli Chapel in the south end of the transept. It has a complete, and almost entirely well-preserved, series of frescoes of the Life of the Virgin by Giotto’s pupil, Taddeo Gaddi, dating from c. 1328–38. Gaddi also designed the stained glass for the windows.

PdM Quite apart from their innovative treatment of space, light and narration, what is wonderful in the frescoes here is the decorative, colourful ensemble, the sense of a whole Bible illustrated around the walls. It gives us an idea of what Giotto’s Peruzzi Chapel might have been like, with the trompe-l’œil and the columns and niches so much more striking in their original and intended colour scheme, harmoniously unifying the whole.

This chapel, dating from the early 14th century, has survived in an unusually intact state. Except, that is, for the frame of the altarpiece. The various panels of the altarpiece itself depict the Coronation of the Virgin and the Glory of Angels and Saints. The whole work is signed by Giotto himself, ‘Opus Magistri Jocti’ (A Work of Master Giotto), but many scholars have detected the hands of various others, including Taddeo Gaddi.

Giotto di Bondone, Funeral of St Francis, 1320s. Fresco. Bardi Chapel, Santa Croce, Florence.

Giotto di Bondone, Ascension of St John the Evangelist, 1320s. Fresco. Peruzzi Chapel, Santa Croce, Florence.

Taddeo Gaddi, east wall of the Baroncelli Chapel showing The Life of the Virgin, c. 1328–38. Fresco. Santa Croce, Florence.

Giotto, Altarpiece, Baroncelli Polyptych, c. 1334. Tempera on wood, 185 × 323 (72⅞ × 127⅛). Santa Croce, Florence. Photo Scala, Florence/Fondo ...