![]()

CHAPTER 1

Back in Time

Before the cattle were unyoked, we saw a female figure emerge from a hole in the face of the cliff bearing what we at first thought to be a sick child but on a nearer approach proved to be a diminutive and emaciated old woman, the mother of her dutiful and, to do her no more than justice, affectionate bearer …

Accompanying her to a low cave formed by an enormous block of stone with a flattened undersurface now blackened by smoke and soot, we found two men of something between the Bushman and Hottentot tribes, one in an old felt hat and sheepskin cloak, smoking tobacco out of the shankbone of a sheep, the other in a red coat, lying outstretched upon his back and fast asleep, with an old musket, marked G R Tower, carefully covered beside him. A few thorn bushes served to narrow the entrance of the cave and partially to screen its inmates from the weather …

A few animals, nearly obliterated, were still visible upon the walls of their dwelling, proving it to have been an ancient habitation of their race; and the men told me they had seen drawings of the unicorn but had never known any one who could testify to the existence of the living animal.1

In this extract from his diary, the British artist and explorer Thomas Baines describes the appalling conditions in which many San people lived at the middle of the 19th century. He had sailed to the Cape of Good Hope in 1842 and, after working in Cape Town as a coach painter, embarked on an extensive journey through the interior of the subcontinent. On this journey, he compiled what is today an invaluable collection of paintings that depict not only scenery but also indigenous people. In 1858 he accompanied David Livingstone along the Zambezi river, where he was one of the first Westerners to see the Victoria Falls.

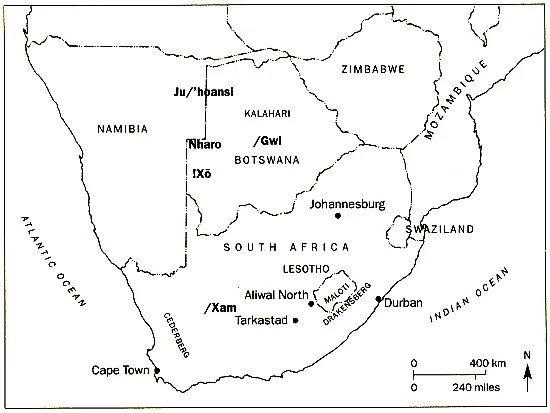

The encounter that Baines describes took place near the present-day town of Aliwal North (Fig. 2). The San whom he met and painted were bereft of the land and animals that had sustained them for millennia (Pl. 2). They drifted from place to place, clinging to what little they could derive from the Western civilization that had engulfed them. Next to the man whom he found sleeping in the rock shelter lay a musket engraved with the name of its former owner; traded tobacco provided the other man with some solace. The San, together with the pastoral Khoekhoe (formerly known as Hottentots), who had for the most part lost their herds and flocks, were caught between two ways of life.

On the rock wall behind the people were the remains of San paintings. Though blackened by smoke and soot, the few remaining images pointed to a rich cultural heritage – but Baines himself was unimpressed by them. He thought the artists were ‘ignorant of perspective’ and in ‘want of skill’.2 The poverty of the San in material things tended to persuade early travellers that they were equally poor in culture and belief, and therefore unworthy of respect.

Nevertheless, Baines did not consider the San whom he met to be poverty-stricken simply because they were, by tradition, nomadic hunter-gatherers. True, mobile people cannot carry much in the way of goods on their long treks. There was more to it, however. The 19th-century San were the victims of two centuries of harassment and dispersal. We read that the young woman in the group had no option but to carry her frail mother on her back. She had no extended family to help her. Even her daughter had been ‘detained in servitude’ by a group of people known as Bergenaars – mountain robbers, as Baines explained. The whole San social system had broken down.

2 Map of southern Africa showing places mentioned in the text. The San groups indicated speak, or spoke, mutually unintelligible languages.

The Bergenaars, a mixed-race group, lived very largely through banditry and stock theft, as did many other culturally and racially heterogeneous groups throughout southern Africa, and indeed the people whom Baines himself met.3 The remnant communities of San had no recourse but to steal cattle and sheep. They therefore joined creolized groups like the Bergenaars and defended their land with their traditional bows and arrows and with newly acquired muskets. Early on, they became feared for their lethal poisoned arrows and their cunning cattle rustling.

This state of affairs gave the colonists the excuse they sought to eradicate the hunters. In the 1770s, the Swedish naturalist and traveller Anders Sparrman wrote: ‘Does a colonist at any time get view of a Boshiesman [as the San were then known], he takes fire immediately, and spirits up his horse and dogs in order to hunt him with more keenness and fury than he would a wolf or any other wild beast.’4 No quarter, no negotiation. Another Swedish naturalist, Carl Peter Thunberg, writing at the end of the 18th century, was appalled by the treatment that the San received at the hands of the colonists. One commando raised to exterminate the Sneeuberg San ‘killed 400 Boschiesmen; of this party seven had been wounded by arrows, but none died’.5

Those who were taken alive by the colonists were no better off. Louis Anthing, who was commissioned in the 1860s by the Parliament of the Cape of Good Hope to investigate the atrocities that were being committed, was shocked by what he found:

Those who went into the service of the new comers did not find their condition thereby improved. Harsh treatment, and insufficient allowance of food, and continued injuries inflicted on their kinsmen are alleged as having driven them back into the bush, from whence hunger again led them to invade the flocks and herds of the intruders, regardless of the consequences, and resigning themselves, as they say, to the thought of being shot in preference to death and starvation.6

Some British colonists (Britain having finally taken full control of the Cape in 1814) tried to blame the Dutch farmers for this state of affairs, but the missionary John Phillip found otherwise:

While England boasts of her humanity, and represents the Dutch as brutes and monsters, for their conduct towards the Hottentots and Bushmen, a narrow inspection … will bring to light a system … perhaps exceeding in cruelty anything recorded in the facts you have collected, respecting the atrocities committed under the Dutch Government.7

Materially poor, culturally rich

The San were an autochthonous people. As archaeological evidence testifies, they and their ancestors lived for many millennia throughout the whole of the subcontinent.8 Then, about 2,000 years ago, they had to contend with an influx of other peoples.9 First, there were Khoekhoe herders in the western, central and coastal regions and, later, Bantu-speaking black farmers along the east coast and the highveld of the interior. Then a more comprehensive threat came in 1652, when the Dutch established a settlement at the Cape of Good Hope. Domestic herds and their colonial owners soon spread into the interior of southern Africa. Thereafter, the San survived in the shrinking interstices of land between the more populous and resource-hungry agricultural economies. In the semi-arid parts of the central interior and in the mountains in the south-east, the San managed to sustain viable communities into the 19th century. By turns, these communities had both good and bad relations with the peoples moving into the subcontinent.

Many settlers, especially missionaries, believed that the San did not have the mental capacity to understand any form of religion. Nevertheless, some colonists did take the trouble to enquire into San beliefs. One of these was Sir James Edward Alexander. A Scottish soldier and traveller, a man of independent financial means, he journeyed up the western side of what are now South Africa and Namibia hoping ‘to discover some of the secrets of the great and mysterious continent of Africa’.10 In particular, he hoped ‘to promote trade, to civilize the native tribes that might be visited, and to extend a knowledge of our holy religion’ (ibid.). He began his long trek in 1835, a time when the colonists entertained a very low opinion of the ‘Boschmans’, as the San were then known.

Alexander, however, discovered that the San were not entirely without religious concepts, albeit very rudimentary ones:

During the journey I had often endeavoured to find out traces of religion among the Boschmans and others; but I had hitherto been very unsuccessful…. [A]mong the Boschmans I had discovered nothing to indicate the faintest trace of religion, but now I did in a singular way…. ’Numeep, the Boschman guide, came to me labouring under an attack of dysentery.

I asked him what had occasioned the disease; and he said it was from having dug for water at the place called Kuisip … without having first made an offering … to Toosip, the old man of the water.

‘Do you say any thing to him when you put down your offering at the water-place?’

‘We say, “Oh! Great father! Son of a Boschman – give me food; give me the flesh of the rhinoceros, of the gemsbok, of the wild horse [zebra or quagga], or what I require to have.”’

I was very glad he had been ill; for owing to this, I found out a trace of worship among a very wild people.11

That Alexander hardly understood this ‘trace of worship’ is today clear. But he at least saw beyond the people’s material poverty. Little by little and very slowly, the view that the San were irredeemably ‘primitive’ began to break down in more educated colonial circles, though not in rural districts.

Today, numerous San linguistic groups still live in the Kalahari Desert, where their ancestors lived for thousands of years. They include the Ju/’hoansi (formerly !Kung), /Gwi, !Kõ, and Nharo. These present-day San are not descendants of people who were recently driven into the desert by other people. They are descended from the aboriginal human populations of the African subcontinent.12 They have become one of the most thoroughly studied of the world’s small-scale, hunter-gatherer societies.13

By comparing the beliefs and rituals of these desert people with what was recorded for the groups, like the /Xam, that lived farther to the south in the 19th century, we are able to see that, notwithstanding regional variations, certain beliefs and rituals were widespread, probably pan-San. These commonalities included complex hunting observances, girls’ puberty rites and the central, all-important healing, or trance, dance.14 Where basic parallels are demonstrable, it is therefore possible to supplement the 19th-century southern ethnographic record by recourse to more recent research in the Kalahari.

Comparisons of this kind highlight the large number of mutually unintelligible San languages.15 When four young Ju/’hoan boys from the northern Kalahari were brought to Cape Town in 1879, it was found that their language was unintelligible to the southern /Xam San people.16 Many San languages have unfortunately died out in comparatively recent times. One of these, the /Xam language, was chosen for the new, post-apartheid South African national motto: !Ke e: /xarra //ke – People who are different come together.17

In the 19th century, a gradual (though unfortunately still incomplete) reassessment of the San was initiated by a small group of people whose work provides the foundation for our investigation of what the San themselves said and thought about the paintings they made in their rock shelters. This group comprised the Bleek family, Joseph Orpen and George Stow.

A remarkable family

Today the history of the Bleek family is well known. Indeed, a scholarly industry has grown up around its various members.18 Wilhelm Bleek (1827–1875) was a German philologist, who came to southern Africa in 1855 to compile a Zulu grammar. While he was working on the Zulu language in the British colony of Natal he heard about the San. He wrote: ‘During the first few months of this year [1856] the Bushmen descended from their impregnable hiding places in the Kahlamba mountains [Drakensberg] to steal cattle again.’19 After a brief but linguistically productive sojourn in Natal, Bleek moved to Cape Town in 1856 to become a court interpreter and, later, curator of the valuable library owned by the British governor, Sir George Grey.

Bleek’s life took a momentous turn soon after he moved to the Cape. He learned that some San men, convicted of sheep-stealing and even murder, had been taken to a jail in Cape Town. He saw this as an opportunity to study their little-known language. He realized that Zulu and other Bantu languages were not in any danger, but that the San languages, quite different from those Bantu languages, were threatened with extinction as a result of t...