![]()

• 1 •

WORD OF MOUTH: MAKING MYTHS

And after the mist, lo, every place was filled with light. And when they looked the way they were wont before that to see the flocks and the herds and the dwellings, no manner of thing could they see: neither house nor beast nor smoke nor fire nor man nor dwelling, but the houses of the court empty, desolate, uninhabited, without man, without beast within them, their very companions lost, without their knowing aught of them, save they four only.

FROM THE THIRD BRANCH OF THE MABINOGI

Myths, like fables, are elusive things. Modern horror films, whether about vampires, ghosts or revived Egyptian mummies, are arguably acceptable because they allow people to explore the darkest aspects of human nature within a safe environment. In a sense, the same is true of myth, but myths are much more complicated. This is in part because they are almost always associated with religious belief – and often magic – and also because contained in mythic tales are answers to some of the most fundamental human concerns: Who are we? Why are we here? Why is our world like this? How was the world created? What happens to us when we die? Myths also explore issues related to initiation rites: birth, puberty, marriage and death. Some, particularly those from the Celtic world, are highly concerned with morality – good and evil, chastity, violence, rape and treachery, war and ethics – with gender-roles, maidenhood, motherhood and virility; and with the ideals of female and male behaviour.

Myths flourish in societies where such issues are not answerable by means of rational explanation. They are symbolic stories, designed to explore these issues in a comprehensible manner. Myths can serve to explain creation, natural phenomena and natural disasters (such as floods, drought and disease), the mysterious transitions of day and night, the celestial bodies and the seasons. They are often associated with the dreams and visions of so-called ‘holy men’, persons (of either gender) with the ability to see into the future and into the world of the supernatural. Myths are inhabited by gods and heroes, and tell of the relationship between the supernatural and material worlds. They can provide divine explanations for the departures of past peoples, their abandoned monuments and burial sites, their houses and places of communal assembly. Myths can explain the origin of enmities between communities and disputes over territory. Finally, myths are often highly entertaining tales that can while away a dark winter’s evening by the fire.

Trackways for the Spirits

No person had ever walked out on the bog but after that Eochaid commanded his steward to watch the effort they put forth in making the causeway. All the men made one mound of their clothes and Midir went up on that mound. Into the bottom of the causeway they kept pouring a forest with its trunks and its roots, Midir standing and urging on the host on every side.

FROM THE WOOING OF ETAIN

Wooden trackway across an Irish bog, built in 148 BC, at Corlea, Co. Longford.

© National Monuments Service, Dublin. Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht

Archaeological finds help connect the mythical cycles to their ancient origins. In the mid-2nd century BC a community at Corlea in Co. Longford, in central Ireland, constructed a great wooden causeway across a marsh to dry land. Tree-ring dating has established that the oak trees used for building this trackway were felled in 148 BC. Beneath the foundations a strange half-human, half animal image carved of ash was buried, perhaps as a foundation deposit, to bless the new road. The track may have been constructed in sections by different groups of people; certainly one section was never completed for there was at least one gap.

Certain Irish myths make references to the building of trackways across bogs. In the story of the divine Midhir and his love, Étain, Eochaid, king of Tar gave the god the ‘impossible’ task of constructing a wooden road across an impassable bog. Another tale relates a quarrel between two communities set to build a track across marshy ground from opposite ends, to meet in the middle. Having almost finished the job, the two groups fell out over its completion and it was never finished. Could this be the Corlea causeway? Could early Irish storytellers have woven into their narratives the remains of ancient roadways that were still visible in early medieval time?

• INTRODUCING THE WELSH AND IRISH MYTHS •

The main myths of Wales and Ireland are contained within medieval manuscripts that date between the 8th and 14th centuries AD, in their extant form. Three cycles of Irish prose stories comprise the principal surviving sources of Irish mythology. Earliest in its written form is the Ulster Cycle, whose focus is the epic tale of war between Ulster and Connacht, the Táin Bó Cuailnge (The Cattle Raid of Cooley), featuring the great Ulster hero Cú Chulainn and the dastardly Queen Medbh of Connacht. Historically, the province of Ulster had lost most of its political clout by the end of the 5th century AD. Its prominence in the Táin Bó Cuailnge argues for the Cycle’s early origins. The first recension (copy) survives in fragments within the 11th-century Book of the Dun Cow, but the language used here belongs more properly to the 8th or 9th century. Another major source for the Ulster Cycle is the 11th-century Yellow Book of Lecan. The other two collections – the Mythological Cycle and the Fenian (or Fionn) Cycle – each survive in 12th-century versions. The first of these contains the most variety, and has vivid descriptions of pagan deities; the focus of the Fenian Cycle is the life of the eponymous Finn, heroic leader of a famous war-band and keeper of divine wisdom.

Pages from the earliest manuscripts of Irish and Welsh myths. Left: from the Book of the Dun Cow, an 11th-century text containing the earliest known recension of the Táin.

Royal Irish Academy, Dublin

Right: from the Welsh Red Book of Hergest, one of the earliest compendia of the Mabinogi.

Jesus College, Oxford

The Welsh myths are preserved in two principal collections of tales: the White Book of Rhydderch and the Red Book of Hergest. The White Book was put together in about 1300 and the Red Book in the later 14th century. The stories that are most rich in mythic content are the Pedeir Ceinc y Mabinogi (the Four Branches [sections] of the Mabinogi), known colloquially as the Mabinogion, and ‘Culhwch and Olwen’. Other important material is contained within other tales, including ‘Peredur’, ‘The Dream of Rhonabwy’, and the fragmentary story ‘The Spoils of Annwfn’. A further branch of myth deals at length with the heroic figure of King Arthur and the Quest for the Holy Grail. It is presented in the medieval French Arthurian Romances, whose best-known author was Chrétien de Troyes. Arthur makes several appearances in the Welsh myths too, particularly in ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ and ‘Peredur’, both of which are hero-tales.

• MYSTICAL VOICES: STORYTELLING FROM •

ORAL PERFORMANCE TO WRITTEN WORD

Celtic myths had their genesis in early traditions of storytelling, of live performance. Just as musicians might travel from court to court to amuse the nobility, or skilled craftspeople to fulfil commissions for new armour or a decorative wine-cup, so poets and storytellers plied their trade. Many would have been peripatetic performers and in their travels they would have spread common stories from place to place. Others, like medieval court jesters, belonged to particular halls, and their tales would perhaps have more of a local flavour. But because the stories were held in people’s heads, they would have grown and adapted organically, and no two tellings would have been exactly the same. So, for example, visiting storytellers might have woven features of the local landscape – mountains, rivers and trees – into their tales for the particular appreciation of local audiences. These mythic stories were alive, changed and grew with time and were embellished according to the skill of the narrator and the experiences of the community who listened to the tales.

‘Our custom, lord,’ said Gwydion, ‘is that on the first night we come to a great man, the chief poet performs. I would be happy to tell a story.’ Gwydion was the best storyteller in the world. And that night he entertained the court with amusing anecdotes and stories, until he was admired by everyone in the court, and Pryderi enjoyed conversing with him.

FROM THE FOURTH BRANCH OF THE MABINOGI

Oracle Stones

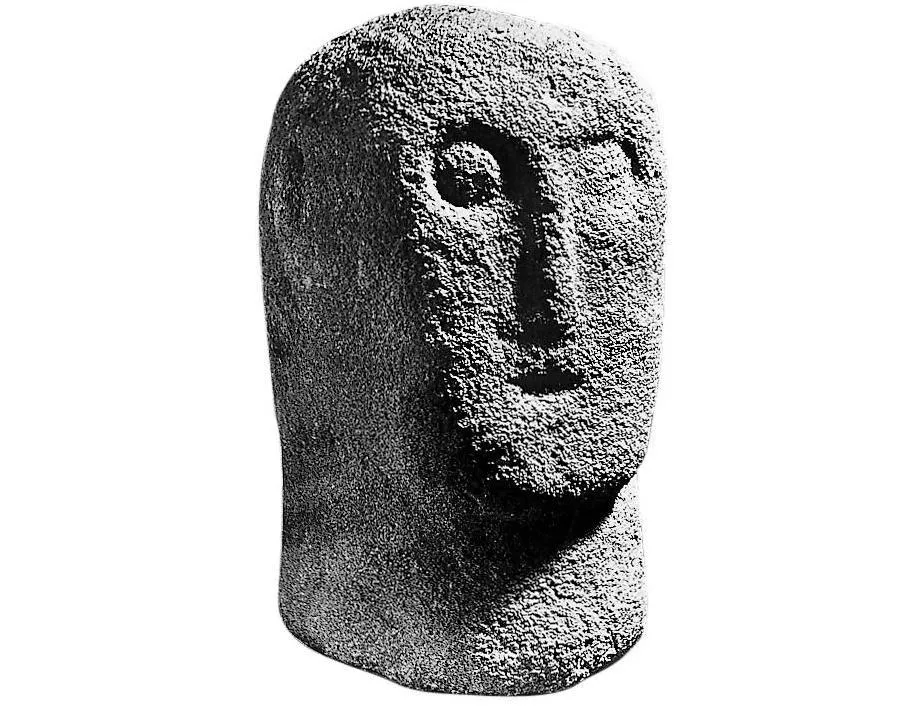

Pre-Christian stone sculptures from Ireland and Wales may represent the storyteller in action. They depict human heads, and on some their mouths are wide open as if in speech or song. A unique carving from Newry, Co. Armagh, is called the Tanderagee Idol. It is the image of a speaking man: his thick-lipped mouth gapes wide, and he appears to wear a horned headdress; the right hand is held diagonally across the body in the typical attitude of an orator, but it grasps something that may be a magical stone. It is tempting to interpret this image as a seer or shaman, wearing the animal-insignia that denotes his shape-shifting status, able to converse with the gods and propound their wisdom to his community. Traditional shamans often assume the persona of animals because they are deemed to possess particularly close links with the Otherworld. So shamans frequently wear animal-skin cloaks or horns. The Tandaragee Idol has not been precisely dated, but it is likely to belong to the late Iron Age or early medieval period.

Iron Age stone figure known as the Tanderagee Idol, perhaps an image of an early Irish storyteller, from Co. Armagh.

Ulster Museum, Belfast

Wales has produced its own ancient ‘oracle stones’. The Roman city of Caerwent in the southeast was the capital of the Silures, a tribe fiercely hostile to the Roman invasion of their territory in the mid-1st century AD. The town developed late and most of its public buildings date to the 4th century. Found at the bottom of a wealthy person’s garden was a tiny shrine in which stood a carved sandstone head, its mouth wide open, again as if speaking or singing. It is easy to imagine visitors to the little sanctuary hearing the voice of the spirits through the medium of a magical speaking head.

Late Romano-British sandstone head from Caerwent, South Wales, with open mouth, perhaps an ‘oracle stone’.

Newport Museum & Art Gallery

The Welsh word for a medieval storyteller was cyfarwydd, and its meaning is key to understanding the storyteller’s role and status in society, for inside the word is a whole package of functions: guide, knowledgeable person, expert, perceptive one. The teller of tales was powerful, for he or she was a curator of tradition, wisdom and ancestral knowledge, all of which served to bind communities together and give depth and meaning to their world. It was not enough to be able to remember and recite a good yarn: stories needed to be carefully constructed and were heavy with significance.

Little is known about storytelling in action. However, just occasionally we are allowed a peep into the experience of the professional teller of tales. It is especially rare for this to occur in the tales themselves, but the Fourth Branch of the Mabinogi provides us with a glimpse into the experience of the cyfarwydd. The magician Gwydion appears at the court of the Welsh lord Pryderi at Rhuddlan Teifi (West Wales) and offers his services as a cyfarwydd. He spends the evening entertaining the court and is declared to be the best storyteller ever known. He is fêted by all the courtiers, and especially by Pryderi himself.

Medieval Welsh storytelling was close kin to poetry, and often the poet and the cyfarwydd were one and the same. Of course, modern audiences can only access the tales through their written forms but, even so, their beginnings as orally transmitted tales are sometimes betrayed by various tricks of the trade. Each episode is short and self-contained, as though to help listeners (and the storytellers themselves) remember them. Words and phrases are often repeated, again to aid memory. A third device also points in this direction, and that is the ‘onomastic tag’, the memory-hook provided by explanations of perso...