![]()

CHAPTER 1 | Face Time: Reinventing the Portrait |

In March 2010, a team of Spanish surgeons performed the first full transplant of a human face. A breakthrough in medical science, the procedure was nevertheless profoundly dislocating, not only for the patient who courageously underwent it following a tragic shooting accident, but also for the age in which it occurred. For the first time in human history, features that had once defined the appearance of one individual were now integral to the countenance of another. Oscar Wilde’s famous assertion, ‘a man’s face is his autobiography’, suddenly required reformulation. A visage could no longer be looked upon to record the traumas and triumphs of a single life but was a register of composite existences. From now on, the essence of identity would be as unfixed physically as it had always been philosophically.

11 Leonardo da Vinci, Mona Lisa, c. 1503–6. Oil on wood (poplar)

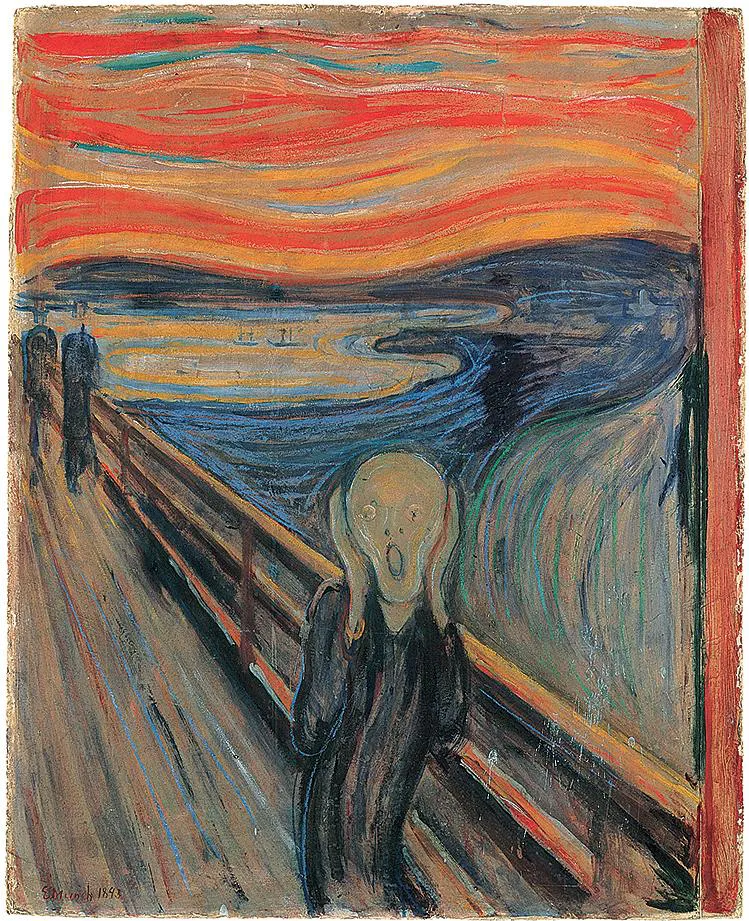

12 Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1893. Tempera and crayon on cardboard

Throughout the history of creative expression, no subject has proved more captivating to both artists and admirers of visual art than the face. Whether one thinks first of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa (c. 1503–6) or Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893), many of the most memorable works of art are portraits. Why are we drawn to the countenances of strangers and the suspended stare of painted eyes? Perhaps, unlike landscapes or abstract compositions, portraits create the illusion of looking back and have the capacity to turn our gaze onto ourselves. Portraits likewise offer our best opportunity to scrutinize the absent artist: the creator and created collapsing into a single expression.

Rationally or not, we attempt to discern from portraits not only an artist’s technical skills, but also his or her grasp of human character and depth of insight. Is the artist empathetic or misanthropic? Lustful or distant? Rigidly realistic or dreamily wistful? From these fictional faces we attempt too to glean what we can of the temperament of the time in which the artist and subject lived. War-torn or peaceful? Prosperous or austere? Are these the eyes of one who looked upon an age of reason or a Romantic era? Just as the Mona Lisa is marvelled upon as a map that can lead us out of the Middle Ages, The Scream, which howls from the threshold of the twentieth century, is seen as an anguished signpost of traumas to come: the horrors of world wars, of holocaust and of modernist dredging of the subconscious.

13 Glenn Brown, America, 2004. Oil on panel

14 George Condo, The Laughing Cavalier, 2013. Acrylic, charcoal and pastel on linen

The years since the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 have seen as great an upheaval in our comprehension of the human face as any age in history. Astonishing medical and technological innovations – from facial-recognition software to full-face transplants – have forced us to focus on the connection between countenance and individual identity. The challenge for contemporary portraitists has been to keep pace with such ingenuity, to reinvent the face for a new age.

For some, such as British painter Glenn Brown, American artist George Condo, Czech miniaturist Jindřich Ulrich and German Surrealist painter Neo Rauch, the way forward has been the way back, scavenging from scrap heaps of history ambiguous ingredients from which a novel countenance can be assembled. Brown’s earliest work, from the start of the 1990s, earned him a reputation as a brash bootlegger who shamelessly lifted subjects from old and new masters alike, from Rembrandt van Rijn to Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Salvador Dalí to Frank Auerbach, whose complexions he audaciously corroded into a leprous pallor. It took the art world several years to come to terms with the unsettling significance of Brown’s work, which relied less on cynical recycling of forebears than on a singular vision of the whole of art history as a closed system in ceaseless decay. To look at portraits such as Joseph Beuys (2001) or America (2004) is to stare into the face of a slow aesthetic decomposition of all the portraits one has ever encountered before. The eternal warmth of Rembrandt’s ambers and golds has been replaced with the slow putrefaction of gangrenous greens and rigor-mortis blues. His countenances are characterized by an intricate swirling of colour, like an alchemist’s alembic percolating with corrosive chemicals that serve to heighten the impression that every portrait is a simmering concoction of every portrait that came before it.

A wryer reconditioning of conventional countenance preoccupies the portraiture of Condo, whose manipulation of precursors such as Picasso and Diego Velázquez is in accord with Brown’s grotesque imagination. For Condo, though, the trajectory of intervention into the works of antecedents is one of crude caricature: a devolution of form in the direction of clumsy parody, as though the whole history of art were breaking down into a crass satire of itself.

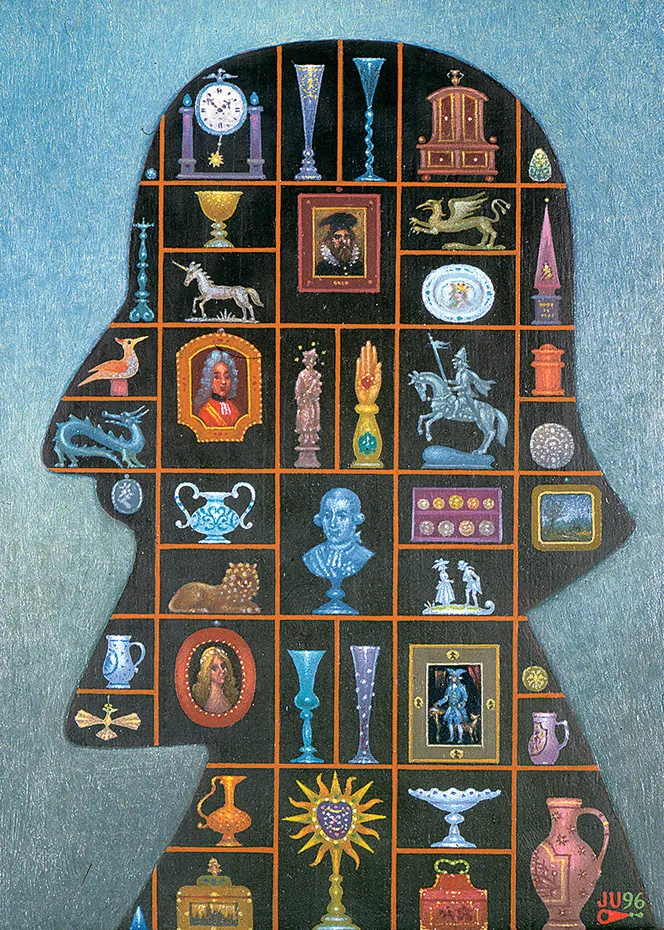

15 Jindřich Ulrich, The Collector, 1996. Oil on wood

Virtually unknown beyond Prague before the Velvet Revolution in 1989 that brought an end to communist control of his native country, the reclusive Ulrich had earned a provincial reputation as ‘the last Medieval miniaturist’ for his countless pocket-sized portraits that managed to merge meticulous old-master technique with innovative and often playful contemporary vision. Rarely larger than a few centimetres in height, Ulrich’s paintings conjure the Bohemian past of Rudolf II’s eclectic court of astronomers and alchemists, necromancers and ne’erdo-wells, by dividing a portrait’s profile into a cabinet of tiny compartments into which still smaller constituent curiosities relating to Prague’s occultist past were carefully tucked away. To peer into the cubbyholes of an Ulrich miniature is to witness the secret safe-keeping from political threat of a people’s at once sophisticated and superstitious past, in anticipation of later retrieval and rehabilitation. For Ulrich, portraiture offers not merely the record of a single individual’s semblance, but provides the possibility for historical conservation and the eventual excavation of what is public, shared and in danger of being forgotten.

A very different kind of artistic resuscitation is evoked by Rauch. Associated with the post-reunification movement known as the New Leipzig School, Rauch’s work involves the blending of past artistic references with contemporary concerns. The figures portrayed by Rauch are often clad in antiquated dress, recalling iconic European revolutionary struggles from the end of the eighteenth century to the beginning of the twentieth. The literal dramas in which these subjects are involved are often indeterminate from the clues provided, aligning Rauch’s imagination in the estimation of many commentators to Surrealism. But where pioneering works that define that earlier movement, such as Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory (1931), were invigorated by emergent ideas concerning psychoanalysis and human consciousness, Rauch’s work is illustrative of an age preoccupied by the brutal dismemberments of history and the recombination of cultural shapes.

The result is works of irresolvable narrative tension, where the past and present struggle for the upper hand. In Rauch’s double portrait Armdrücken (Arm Wrestling) (2008), for example, two figures from what appear to be distant eras lock fists across a nondescript table in a curiously timeless interior, straining for control. Complicating the composition is the viewer’s suspicion that the two men may be aspects of the same individual – reincarnations of each other – a split in personality occasioned less by psychological disorder than by the ravages of time. The hunch is made all the more intriguing by the near resemblance of both to the artist himself. In Rauch’s work, identity is an elusive value that involves reconciling the temporally irreconcilable: the past and the present, then and now.

Awkward unions of the historical with the contemporary likewise enliven the work of the New York-based portraitist Kehinde Wiley. A restaging of Jacques-Louis David’s Napoleon Crossing the Alps at Grand-Saint-Bernard (1801–5) is characteristic of Wiley’s technique of reimagining paintings by canonical artists of the Western tradition set against a dislocating intricacy of regal and floral designs, which serves to amplify the cultural clashes the artist is choreographing. Wiley’s reinvention, Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps (2005), updates an iconic art historical scenario by substituting an African-American man clad glamorously in today’s fashion for the white European figure at the centre of the old master’s original work. ...