- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

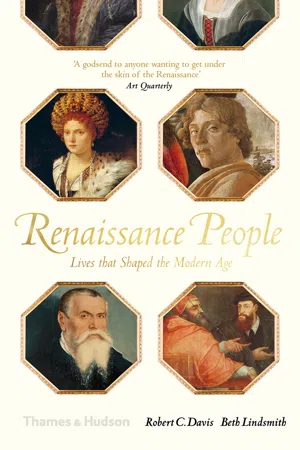

This intriguing book highlights and illustrates nearly 100 notable lives from between 1400 and 1600. Through these very readable short biographies, patterns in the history and art of the Renaissance become clear.

Some names are famous - Leonardo, Luther, Lorenzo de Medici and Machiavelli - but others will be new to many readers: artists, philosophers, politicians, scientists, rebels and reactionaries, as well as an acrobat, an actress and even a star comedian.

'This attractive volume can be and should be on the shelves of anyone interested in the history and culture of the Renaissance' - The Historical Association

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Renaissance People by Robert C. Davis, Beth Lindsmith in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & History of Renaissance Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. Old Traditions and New Ideas

1400–1450

THE YEAR 1400, WHEN THIS STORY BEGINS, WAS NOT AN ESPECIALLY PROMISING one for Europeans. The bubonic plague, after its devastating arrival in 1348–50, had returned every generation thereafter, driving the population into an exceptionally long demographic trough that bottomed out with a devastating outbreak in 1400–01. The Holy Roman Empire, at the heart of the continent, was split with a particularly bitter leadership crisis in 1400, with one emperor deposed, another murdered, a third deserted by his army and much of Germany falling into banditry and chaos. Europe’s two leading monarchies were equally crippled. In 1399 the English king, Richard II, had been removed in a coup d’état whose repercussions echoed for nearly a century, while the part of France unoccupied by English troops was ruled by a thoroughly insane monarch known, appropriately, as Charles the Mad. Finally, the papacy, potentially the continent’s moral compass, was hopelessly split between rival claimants in Rome and Avignon – one of them illiterate and the other abandoned by most of the cardinals who had elected him – in what a later historian called ‘one of the saddest chapters in the history of the Church’. Believing that this papal decline presaged or even invited God’s imminent retribution, in 1399 penitent laymen began wandering from city to city in Catalonia, Provence and Italy, flagellating themselves, gathering in great throngs and predicting the collapse of society.

Courtyard of the Palazzo Medici-Ricciardi, Florence (1445–60). Cosimo de’ Medici’s palace, designed by Michelozzo dei Michelozzi, served as both the Medici’s private dwelling and their political headquarters.

Massimo Listri/Corbis

The decay of such venerable institutions as the Holy Roman Empire and the papacy was not permanent, of course, and, despite being quintessential medieval creations, they eventually found the road to modernization and rejuvenation, as did the still feudal monarchies of England and France. Europe also emerged, albeit slowly, from its demographic slump, and even during the population crisis of the early 15th century some economic advantages emerged from the wreckage. Although there were far fewer Europeans in 1400 than in 1300, the available wealth in some ways remained constant, meaning that individual survivors were demonstrably wealthier, with more and better farmland to feed the cities, which were no longer so crowded and fetid. The artisans who came seeking work, being fewer in number and more in demand, found significantly higher wages, along with cheaper housing. As long as they could avoid the plague, the upper classes too did better for themselves, with undiminished patrimonies going to a reduced number of heirs. The increasingly complex finances of these elites gave rise to more nimble and effcient systems of banking and trade, while their desire to stand out from their peers and enjoy whatever life they were given created an explosive demand for luxury crafts, palaces and works of art.

This demographic and economic confluence especially benefited Europe’s two most urbanized centres – the Low Countries and northern Italy. The wealthy textile and trading cities of Flanders and the Netherlands, under the benign if not always enlightened rule of Philip the Bold, entered an era of particular prosperity, expressed through building, land reclamation and the innovative work of such artists as Jan van Eyck. The essentially autonomous towns of northern Italy, linked only tenuously to a negligent Holy Roman Empire, also enjoyed a period of growing wealth, and if most of these free communes had by 1400 found themselves usurped by local lords, a few oligarchic republics still maintained some of the trappings and much of the intellectual ferment of populist rule.

Jan van Eyck, The Virgin of Chancellor Rolin (c. 1430). Van Eyck defied tradition by placing patron and saint on the same plane, creating a new genre in the process. Known as ‘holy conversations’, compositions of this type became popular in the South, where Italian artists adopted the style.

Musée du Louvre, Paris

In much of northern Italy this ferment expressed itself in the rediscovery of the peninsula’s Classical heritage. Uniquely among major European societies, the Italians could confidently embrace their own past – the Roman Republic and Empire – as a culturally superior era. Extensive, if often enigmatic, ruins had existed for centuries, but by the late 14th century the writings of Latin masters were increasingly being copied and disseminated. As educated Italians uncovered these remnants of their national legacy, many experienced a quasi-religious enthusiasm, dreaming up family trees that reached back to Aeneas or seeking to identify every public building in Republican Rome. This passion for Classical roots had a way of spilling out beyond the preserve of scholars, however, as wealthy merchants asked their architects to design palaces based on the teachings of Vitruvius, military commanders studied the experiences of Caesar and Pompey, and Republican apologists applied Cicero’s notions of public service to their own programmes of education and government.

From the late 14th century on, Italians made great use of their Classical past, but their enthusiasm for purging Latin of neologisms, discovering original texts and applying what they found to their own cities, buildings and families could easily have remained a localized, parochial movement. Europeans beyond the Alps, especially those whose past connections with Imperial Rome had been hostile, tenuous or forgotten, had little reason to rush to embrace the study of Latin letters. The Church, which might have provided a conduit to take Latin studies beyond the Alps, was too firmly set against the great majority of Roman pagan authors.

In the years just before 1400, however, the Italians broadened their Classical studies, as the Florentines invited Manuel Chrysoloras to come from Constantinople to teach them Greek. Cicero and other Romans had convinced Italians of the debt that they wed their Greek predecessors, but it was not certain that Italians would take the step of mastering Greek themselves: the language was both diffcult and largely forgotten, and the culture more alien than those past influences would make it seem. That they did so was not just to their own intellectual credit. By embracing Greek, Italian scholars and antiquarian enthusiasts shifted their studies from their own, Latin past to create the notion of a larger world of the Classics, one that encompassed the entire ancient world rather than just their Roman ancestors. Between 1400 and 1450, as they mastered Greek and secured its key texts, Italians also launched a genuine, European Renaissance, one proposing the rebirth of a Classical past broad enough to become a movement across the continent.

Manuel Chrysoloras

A GREEK BEARING GIFTS

c. 1350–1415

ONE OF THE MOST CHARISMATIC FIGURES OF THE EARLY ITALIAN RENAISSANCE WAS not Italian at all but Greek. Born into an ancient family of Constantinople, Manuel Chrysoloras mastered the Greek Classics while still a youth. A bright light of the Byzantine court and personal friend of Emperor Manuel II Palaeologus, Chrysoloras was a natural choice as Byzantium’s ambassador to the West. In 1390–91 he went looking for allies to help defend his fading homeland against Turkish encroachment and, although he never managed to find any meaningful military or financial support, he did uncover a tremendous, unfulfilled thirst among Italians for Classical Greek letters.

This anonymous drawing of Manuel Chrysoloras, dating to the early 15th century, is inscribed ‘Master Manuel, who taught Greek grammar in Florence, 1400’.

Musée du Louvre, Paris

Although rediscovery of the Classics – the great enterprise that made up the core of the Italian Renaissance – was already well under way by the late 14th century, scholars remained handicapped by their inability to read Greek, the knowledge of which had all but died out in the West by the year 1100. The Classical Greek and Hellenist canon – Homer, Plato, the Athenian dramatists, the lyric poets, the satirists and the great scientists – was consequently lost to scholars, who suffered all the more since their favourite Latin authors often proclaimed their literary debt to their Greek forebears. Those wishing to experience this ultimate source of Western culture could only make do with bad translations out of Arabic or struggle over Greek originals on their own. Petrarch owned a copy of Homer, which he found tantalizingly inaccessible, while Boccaccio had a go at translating the Iliad, but the results were neither literary nor especially accurate.

In 1391 Chrysoloras was in Venice, where he met the Florentine Roberto Rossi, who wrote enthusiastically of the Byzantine’s broad knowledge of Classical Greek letters to the chancellor of Florence, Coluccio Salutati. Mustering support from some of the wealthiest and most cultured Florentines, Salutati sent an emissary off to Chrysoloras, who had already returned to Constantinople, offering him a professorship at the University of Florence and giving him a long shopping list of Greek works, both to use as teaching tools and to lay the foundation of a Greek library in Florence. Chrysoloras took his time negotiating over his salary and did not arrive until 1397, but once he took up his post he readily grasped that his primary duty was to make ancient Greek literature available to Italian students. Training pupils to read and comprehend a dead language was, at this time, a novel undertaking. Chrysoloras saw that turning Classical Greek into Latin – the common language of Florence’s literate elite – was something of an art form, requiring his students to master the spirit of the ancients as well as their literal words, to produce texts that were all faithful to the original while still elegantly translated.

During his stay in Italy, Chrysoloras gave hundreds of aspiring Classicists their first exposure to the Greek letters. An inner circle of his best students remained excited and united for the rest of their lives by the knowledge, as Leonardo Bruni put it, that they were the first Italians in over 700 years to have mastered Classical Greek. Inspired by their master, they produced innumerable translations that made Florence the centre of 15th-century humanism and placed it at the very heart of the Renaissance.

Chrysoloras himself remained just three years in Florence, and then, in typical academic fashion, he was poached by Florence’s great rival, the duke of Milan, to teach at the University of Pavia. Before long, however, Chrysoloras was again on the move, visiting universities in Bologna and Padua. Eventually his masters back in Constantinople drafted him away from teaching and assigned him to diplomatic missions. He travelled to Paris, Rome and Germany, seeking (though rarely finding) funds and support for the failing Byzantine Empire. Chrysoloras’s ecumenical inclinations also allied him with the papacy in its attempt to reconcile the Greek and Latin Churches. It was while on his way to the Council of Constance, as the Greek Orthodox Church’s representative, that he died suddenly in 1415.

During the century that followed, other Greeks, some more able scholars than Chrysoloras, came to Italy. None stirred up quite the excitement that he had, however, either in the few years of his active teaching or in the decades after his death. Although he was not a prolific writer, his translations into Latin of Homer and of Plato’s Republic immediately became seminal works in the Greek Classics, used by Italians as models for their own efforts. Years after his death, in 1484, his Erotemata (‘Questions’), arguably the first Greek grammar, was published in Venice and won pre-eminence among scholars of both Classical literature and the New Testament.

Map of Constantinople by the Florentine cartographer Cristoforo Buondelmonte, made in 1422 – seven years after Chrysoloras’ death. Clearly portrayed are Hagia Sofia, the Hippodrome and, across the Golden Horn estuary, the Galata Tower.

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris

Christine de Pizan

DEFENDER OF WOMEN

c. 1364–c. 1430

‘AND I WHO WAS FORMERLY A WOMAN, AM NOW IN FACT A MAN,’ WROTE CHRISTINE DE Pizan in The Book of Fortune’s Transformations. The line could come from a modern newspaper headline, but is actually from a 15th-century allegory, an autobiographical tale of a woman for...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- About the Authors

- Other titles of Interest

- Contents

- Capturing the Renaissance

- 1. Old Traditions and New Ideas

- 2. Europeans at Peace

- 3. The Emerging Nations

- 4. Sudden Shocks

- 5. The Collapse of the Old Order

- 6. The New Wave

- 7. The Framing of Modernity

- Further Reading

- Sources of Quotations

- Sources of Illustrations

- Index

- Copyright