![]()

1. The Alchemy of Desire

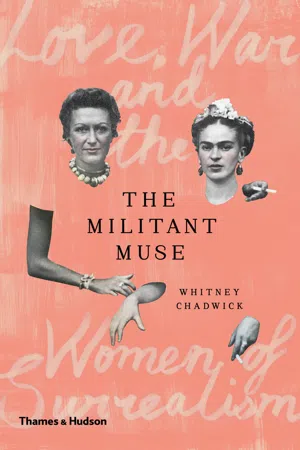

Valentine Penrose and Alice Rahon Paalen, India 1937

André Breton, Automatic Writing, 1938

For centuries the French have withdrawn to the packed beaches of the Côte d’Azur and the campgrounds of the Atlantic Coast to escape the wave of tourists that floods the city of Paris in August. Those forced by circumstance to remain behind can only dream of release. The summer of 1939 was exceptional only in the feelings of anticipation and dread that hovered over otherwise mundane holiday activities, from picnics at the beach to hikes in the mountains. Closer to home, conversations about safe zones and neutral countries led to intense debates in cafés and on benches along the Seine that daily changed as, with one eye on Germany, city-dwellers began to debate the wisdom of flight from the spectre of war and eye the possibilities for relocation with increasing intensity.

Among the general public, the outbreak of war in 1939 stunned those who believed that the First World War had ended international conflict. For the surrealists, many of whom had fought in the earlier war, this new conflict represented a terrifying new irruption of the irrational into everyday reality – and it awakened many women, both among the surrealists and elsewhere, to lives very different from those they had envisioned.

Surrealism, conceived amid the ashes of the First World War, had been nourished by the nihilism of young poets and artists who gathered in Zurich in 1916 to reject war, nationalism and artistic conventions in the name of ‘Dada’ – a nonsense syllable allegedly plucked at random from a dictionary. While the Dadaists had waited out the war in neutral Switzerland, thousands of other young artists and writers had joined the ranks of the mobilized, where their politics, beliefs, art and writing were shaped by the destruction and trauma they experienced. Many did not survive.

Demobilized, unemployed and disillusioned, the poet André Breton had returned to Paris in 1919 to confront a society he had come to despise and a culture whose values he held responsible for the senseless slaughter of hundreds of thousands of young men. Wandering the city streets and spending hours in cafés with fellow poets and old friends, he vented his anger at an educational system he rejected for glorifying the history of war and conquest, and a literary establishment that he saw as effete, complicit and isolated from political and social realities. Determined to challenge beliefs long embedded in the history of the West – among them reason, rationality and binary thinking – he found support in a group of young poets and painters who shared his views, his antipathy to the polarities that underlay Western rationalism and his activism in the name of art and politics.

Inspired by the examples of Freud and Karl Marx, and insistent that sexuality respond to and express both the romantic and the subversive, the surrealists would mine the work of writers and artists from Lewis Carroll to the Marquis de Sade, and from Caspar David Friedrich to Giorgio di Chirico. Struggling to define roles for art and politics that were radical and transformative, the group that gathered around Breton at the end of the war in 1918 would infuse poet and critic Guillaume Apollinaire’s term ‘surrealism’ – first used in 1917 to describe his satirical play Les mamelles de Tirésias (The Breasts of Tiresias) – with new meanings that embraced the power of the dream and the unconscious.

The interests of the young poets and painters in Breton’s circle after the First World War lay not in claiming spontaneous expression as avant-garde literature, but in using it as an investigative medium that merged the conscious and the unconscious and was often expressed in images of night, death and exotic voyages of discovery.1 The surrealists’ belief in the efficacy of such ‘psychic journeys’ of discovery was soon identified with the power of desire.2 Images of the surrealist woman would play an important role in the male surrealists’ longing to enter the enchanted world they believed lay outside rational apprehension. Toward that end, they cultivated an image of the femme-enfant – woman-child – as an enchanting creature whose youth, naiveté and purity were believed to facilitate her access to the unconscious realms that nourished surrealist imagery.3 During the 1930s, her powers became embedded in images of specific women: from painter and poet Alice Rahon Paalen, whom the male surrealists saw as an embodiment of Lewis Carroll’s ‘Alice’, to Leonora Carrington, Max Ernst’s ‘Bride of the Wind’; and from Valentine Penrose, ‘the muse of Gascony’, to Breton’s second wife Jacqueline, the subject of much of his love poetry.

Surrealism provided a lasting community and rich friendships for women as well as men, but it was often in their relationships with one another that the women of surrealism found the emotional support that enabled their most personal and most complicated decisions during the war years. On Jersey, Claude Cahun and Suzanne Malherbe committed themselves to resisting the German occupation of the island. Their political commitments led to arrest, imprisonment and death sentences. Letters written by Lee Miller during the bombing of London chronicle the role of community during the Blitz when often, ‘ten or more friends…slept on the floor of the kitchen corridor…either bombed out of their own flats – or isolated by the presence of a time bomb – or just thinking that Hampstead was safer’.4

The poems Valentine wrote in the 1940s and the photographs Lee took of London under attack reflect women’s anger at the war’s destruction of culture, urban life and civilization as they experienced it. A photograph of Leonor and Leonora taken in 1952, on the occasion of Leonora’s first solo exhibition in Paris after the war, provides some sense of the lasting power of these friendships even after years of separation and loss. The two women – their beauty doubled and magnified by Leonor’s innate theatricality, as well as by the exotic setting on the rue Payenne – pose in front of fragments of two paintings by Leonor of large expressionist human heads. A dense cloak of jet-black feathers envelops both of the artists. It lends the twinned image an air of mysterious power that resonates in the intensity of their gazes as well as in their decision to pose themselves as doubles – ‘the two Leonors’, as they had imagined themselves in the 1930s.

Years later, the 1930s would be remembered for the emergence of the women of surrealism into artistic maturity. Thus it was that on a sunny spring day in 1937, thirty-nine-year-old Valentine Penrose posed alone on the aft deck of a small steamer somewhere off the coast of India or Egypt (see page 29).5 Dressed in a fitted sleeveless shift embellished with a line of bell-shaped buttons, her hair pulled back in a sleek chignon, the poet stares directly into the camera and into the face of the unseen figure behind the lens. Crisp shadows, strong contrasts of dark and light, and the satisfied smile that warms her normally serious features reinforce the illusion of blue water, warm sunshine and new adventures. These adventures included the recent publication of her second book of poems, and the realization of her dream of sharing the ‘marvels’ of India with her closest female friend, Alice Rahon Paalen.6

The two women had first met in the South of France in 1929, and reconnected in Paris in the early 1930s. Married to painters in the surrealist circle, they, along with their partners, had embraced André Breton’s call for a ‘liberation of the mind’ through political and artistic activism.7 Both had entered the surrealist world as aspiring poets and adored muses; both benefited from the support and assistance of well-known male poets and admirers, from Breton and Paul Eluard to Wolfgang Paalen and Roland Penrose. Nevertheless, their struggles toward an artistic maturity that embraced the power of female desire as a creative principle would be shaped as much by friendships with other women as by those with men.

Valentine and Alice had much in common, including beauty, intelligence and determination. They shared the experience of a rural childhood in remote and rugged areas of France, as well as their love of nature, books, ancient art, long walks, magic and mystery. Their friendship would ignite passion, sexual attraction and intense creative dialogue. While Valentine, daughter of a devoutly religious mother and a father who had been a hero of the Battle of Verdun, brought an uncompromising intensity to her search for spiritual awareness, Alice, raised in Paris by parents who worked as a valet and a cook, contributed a sense of wonder and sweetness to the friendship.

Captivated by her colleagues’ subversive and confrontational practices as artists, Alice shared the male surrealists’ vision of a couple in which Woman embodied the role of muse, and women (preferably young, beautiful and enchanting) were extolled as beings of mystery and seductive power.8 Valentine – brilliant, uncompromising, self-obsessed and inclined to mysterious ailments and gnawing dissatisfactions – instead fought to reconcile the life of the mind, and the ‘valuable’ work she believed herself destined to do, with marriage and domestic life. ‘This energy and waste each day, in small tiring tasks…in general domestic [work], which are at heart without initiative because that is their role…’ she wrote to her husband Roland Penrose in 1931, after six years of marriage. Although she remained the ‘muse of Gascony’ in his eyes, as time passed she would increasingly see marriage as a trap that had imprisoned her ‘in the tedium of domestic and conjugal life’.9

Alice, six years younger than Valentine and recently married, chose, initially at least, to embrace the role assigned to her by male surrealists: that of Lewis Carroll’s heroine. She welcomed their belief that, in the words of Louis Aragon, ‘human liberty…rested in its entirety within the frail hands of [Carroll’s] Alice’.10 If photographs of Alice often convey an image of femininity designed to appeal to the surrealist imagination, they also freeze the poet as many male surrealists would later remember her: a young woman wrapped in a hazy glow of beauty, charm and a sense of irresistible wonder. Among the most striking of the many photographs of her taken in the 1930s and 1940s are those that capture her delicate, childlike features partially screened by a seductive fall of long chestnut hair. Her gaze is at once serene and wistful. A childhood accident had resulted in a broken hip with long-term complications, contributing to the air of fragility that surrounded her.

Alice’s early poems, as well as her later paintings, resonate with a view of the artist as shaman, sibyl or wizard, a being capable of sharing ‘in the manifestation of spirits and forms’.11 Like Valentine, she cultivated an intense relationship with nature and femininity. But unlike Valentine, she preserved what one art historian who knew her later in Mexico called ‘the gaze of childhood’.12

Valentine, on the other hand, had delivered the first of many challenges to Roland on the couple’s wedding day in 1925. Her wedding gift to him, a small drawing, bristles with irony and resistance. A combination of pencil sketch and collage, it hangs today in the sitting room at Farley ...