![]()

![]()

DISORDER AND CREATION

Understanding ancient Egyptian thought on creation, or indeed reconstructing Egyptian myth overall, is like trying to piece together a jigsaw puzzle when the majority of the pieces are missing and someone has thrown away the box.

In the past, faced with scattered, diverse and apparently contradictory remnants of creation myths from different parts of the country, Egyptologists divided these mythic snippets according to the cult centre that they assumed had produced (or standardized) the source material – scholarship on these would refer to ‘the Memphite Theology’ (from the city of Memphis) or ‘the Heliopolitan Theology’ (from Heliopolis). Sometimes it was argued that these cult centres, with their various interpretations, were ‘competing’, implying that Egypt’s priests snubbed their noses at their counterparts in different cities because one might prioritize the god Amun in his guise as ‘the Great Honker’ over the divine cow that engendered Re.

Perhaps they did. But whatever the case may be, these various creation accounts, in actuality, display remarkable cohesion, exhibiting the same fundamental themes and following similar structures. The regional cult centres, it seems, put their own spin on generally agreed mythological essentials, emphasizing the roles of particular actors, phases or aspects of creation, and substituting their own local gods for those mentioned in other versions. In this way, Egypt’s various priesthoods put forward alternative, rather than competing, views, thereby reducing the risk of inter-faith fisticuffs.

So, although no universally followed creation myth existed, there was, at least, an overarching concept – a shared foundation – for how creation generally occurred: deep within Nun (the limitless dark ocean) a god awakened, or conceived of creation. Through his power, he, or his manifestations, divided into the many aspects of the created world, creating the first gods and the first mound of earth to emerge from the water. Afterwards, the sun – in some accounts the independent eye of the creator, in others, newly hatched from an egg – dawned for the first time, bringing light to where once had been darkness.

The god Nun raises the solar barque into the sky.

The Hermopolitan Ogdoad flank the solar barque: four on each side.

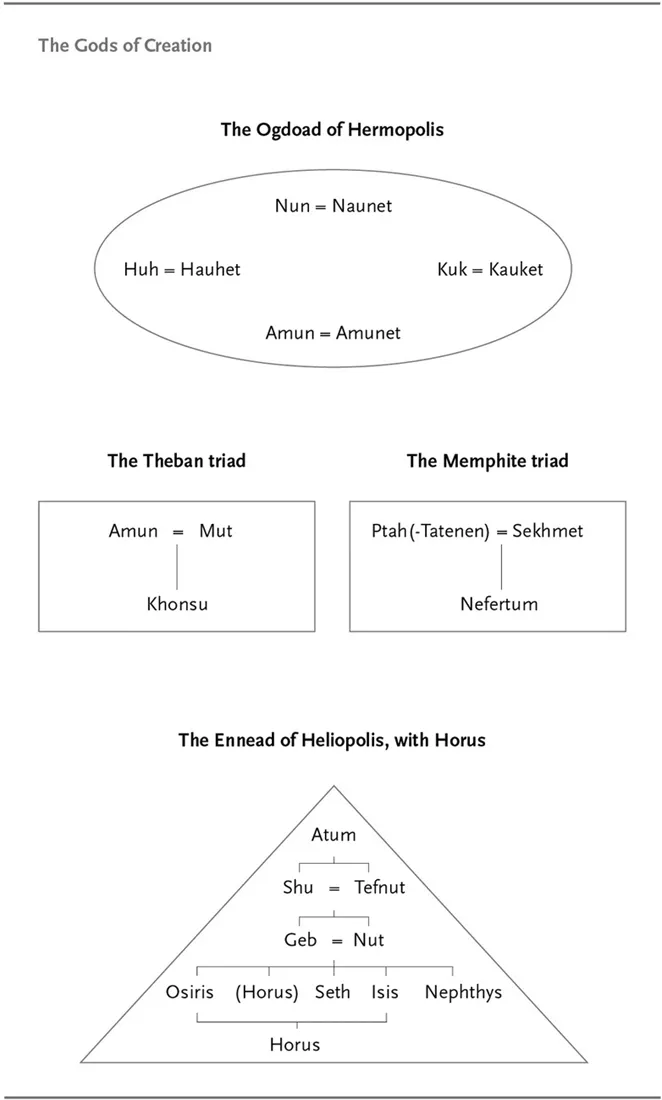

During the New Kingdom, in about 1200 BC, there was an attempt at Thebes to unify Egypt’s main traditions under the god Amun as ultimate creator. This period is, therefore, a perfect standpoint from which to describe creation in more detail, as its texts provide the best insight into the Egyptian conception of where the world came from, while also incorporating the preferred traditions of the country’s most important cult centres – predominantly those of Hermopolis, which focused on the eight gods (Ogdoad) of the pre-creation universe (see below); of the god Ptah’s temple at Memphis, in which the spoken word brought all things into existence; and of Heliopolis, in which the god (Re-)Atum evolved from a single egg or seed into the physical world. Thus, in this chapter, drawing on the work of Egyptologist James P. Allen, and guided by quotations from the Ramesside Great Hymn to Amun – a unique text that presents the conclusions of the Amun priesthood’s theological explorations – we will investigate the creation of the world.

Nun – The Infinite Waters

The pre-creation universe is an infinite body of water, an expanse of darkness, inert and motionless; a place to bring a submarine rather than a spaceship. There is no separation of the elements, no earth and sky, nothing is named, and there is no death or life. It has existed in this form for all eternity, unending, still, silent. Though beyond true human comprehension, to conceptualize and discuss this infinite watery expanse, the Egyptians personified its intertwined aspects as indissoluble male and female couples – the males as frogs and the females as snakes. There was Nun and Naunet as the limitless waters; Huh and Hauhet as infinity; Kuk and Kauket as darkness; and Amun and Amunet as hiddenness. These forces are often collectively referred to as the eight primeval gods of Hermopolis, or the Ogdoad (from the Greek for ‘eight’).

The shape of this pyramidion probably represents the first mound of creation.

To the theologians of Hermopolis, who emphasized these forces of pre-creation in their myths, the eight gods created the first mound of earth (or island) together, and then formed an egg from which the sun god hatched. Depending on the myth at hand, sometimes the sun is said to hatch from an egg laid by a goose called the Great Honker, or by the god Thoth (see p. 51) in the form of an ibis. In other variations, the eight gods create a lotus in Nun, from which the sun is born, first taking the form of the scarab beetle Khepri and then as the child-god Nefertum whose eyes, when open, gave light to the world.

Of the eight aspects of the pre-created universe, Nun, as the limitless waters, was of particular importance. Though sometimes depicted like his male companions as a frog, he could also be shown as a human with a tripartite wig, or as a fecundity figure, representing bounty, fruitfulness and fertility, for, as we shall see, though Nun was inert and motionless, dark and infinite, he was also generative – a place of birth and possibility. This might seem counterintuitive: how can a place of darkness and disorder be a force for growth and life? As an optimistic civilization, the Egyptians saw in Nun potential for being and regeneration: light comes from darkness, land emerges from floodwater with renewed fertility, flowers grow from dry, lifeless seeds. The potential for order existed within disorder.

It is from within Nun that all things began.

Amun ‘Who Made Himself into Millions’

The Eight were your [Amun’s] first form…

Another of his [Amun’s] forms is the Ogdoad…

THE GREAT HYMN TO AMUN

Amun, listed above as just one of the eight primeval gods, was by 1200 BC of unparalleled importance in Egyptian state religion, so much so that the Ogdoad of Hermopolis was now regarded as the first development of his own majestic hidden power. The Egyptians depicted Amun as a man with blue skin, wearing a crown of two tall feathered plumes. His title ‘the Great Honker’ demonstrates his association with the goose, the bird who broke the silence at the beginning of time with his honking; and he could also be shown as a ram – a symbol of fertility. Although Amun’s divine wife was normally said to be Mut (see box opposite), as one of the primeval forces of Nun, he found his female counterpart in Amunet (who is sometimes shown wearing the crown of Lower Egypt and carrying a papyrus-headed staff).

King Seti I (right) bows his head to the god Amun-Re.

In the Middle Kingdom (2066–1780 BC), Amun rose to prominence in the Theban region, and in the New Kingdom (1549–1069 BC) reigned supreme as ultimate deity, referred to as King of the Gods. Representing all that was hidden, Amun existed within and beyond Nun, transcendent, invisible, behind all things, in existence before the gods of creation, and self-created. He ‘knit his fluid together with his body to bring about his egg in isolation’, we are told, and was ‘creator of his [own] perfection’. Even the gods did not know his true character.

He [Amun] is hidden from the gods, and his aspect is unknown. He is farther than the sky, he is deeper that the Duat [the afterlife realm]. No god knows his true appearance, no processional image of his is unfolded through inscriptions, no one testifies to him accurately.

THE GREAT HYMN TO AMUN

Amun’s inaccessibility is probably a good thing, as we are also informed that anyone who ‘expresses his secret identity, unknowingly or knowingly’, would instantly drop down dead.

Simultaneously within and beyond Nun, Amun, the ultimate hidden deity, decided to create the world:

He began speaking in the midst of silence…

He began crying out while the world was in stillness, his yell in circulation while he had no second, that he might give birth to what is and cause them to live…

THE GREAT HYMN TO AMUN

Amun, Mut and Khonsu: The Theban Triad

According to Theban theology, Amun’s wife was the goddess Mut. She was depicted predominantly in human form, but also as a lioness. Mut was a divine female pharaoh, and served as a mother goddess; consequently, she can be shown wearing the Double Crown of Upper and Lower Egypt, and a vulture headdress, associated with goddesses and queens. Amun and Mut’s trinity was completed with their son, Khonsu, depicted as a child with full and crescent moons together upon his head (see also pp. 122–23).

Ptah – The Creative Mind

You took your [next] form as [Ptah]-Tatenen…

He [Amun] is called [Ptah]-Tatenen…

THE GREAT HYMN TO AMUN

Amun’s straightforward, intellectual act of thinking and speaking required the intervention of another god: Ptah, god of arts and crafts, the divine sculptor and the power of the creative mind. To the priests of Ptah, all things were a ‘creation of his heart’: whether deities, the sky, the land, art or technology, each was conceived of and spoken into existence by their god. Worshipped primarily at Memphis, near modern Cairo, Ptah was shown as a man tightly wrapped in cloth like a mummy, standing on a pedestal, gripping a sceptre, wearing a skull cap and with a straight beard (unusual for a god, as they normally preferred curving beards). He formed a family triad with the volatile lion goddess Sekhmet, and their son Nefertum, depicted as a child with a lotus flower on his head. From the Ramesside Period, when the Great Hymn to Amun was composed, the god Tatenen (‘the risen land’) was regarded as a manifestation of Ptah; consequently, the two were united as Ptah-Tatenen, a combination of divine sculptor and the first land to rise from the waters of Nun....