eBook - ePub

The Koreans

Contemporary Politics And Society, Third Edition

- 356 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In this new edition, Donald Clark has thoroughly revised and updated Donald Macdonald's widely praised introduction to Korea, describing and assessing the volatile and dramatic developments on the peninsula over the last five years. Remaining true to Macdonald's original conception, Clark has reworked the existing text from the perspective of the mid-1990s to take account of the enormous political and economic changes in South Korea, the evolving relationship between North and South, and the implications of North Korea's leadership transition and nuclear capability.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Koreans by Donald S Macdonald,Donald N Clark in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Asian Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction: Land, People, Problems

Storm Center of East Asia

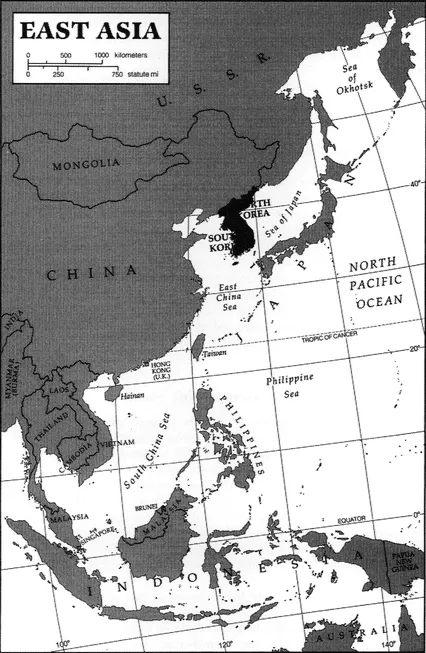

The Korean peninsula is fated by geography and history to be the storm center of East Asia, For centuries, it has been both bridge and battleground among its neighbors. Three of the world's greatest nations—Russia, China, and Japan—sur-round Korea. Each of them considers the peninsula to be of major importance to its own security and each, in the past century, has sought to dominate it. Since 1945, the United States has also had a major security interest in Korea. Thus, far more than most of the U.S. and European public realize, Korea is of vital importance to the peace and progress of this dynamic region.

The Korean people have virtually no record of aggressive ambition outside their peninsula. More than a thousand years ago, Korea was a major, but wholly peaceful, influence on the growth of Japanese culture. Yet it has endured many invasions, great and small, in its two thousand years of recorded history. It has suffered five major occupations by foreign powers. Four wars in the past hundred years were fought in and around Korea.

Despite these trials, Korea had a history of well over a millennium as a unified, autonomous nation until Japan took it as a colony in 1910. The victors in World War II, who drove out the Japanese, divided the country for military convenience in 1945. The Soviet and U.S. occupiers then proceeded to create two mutually hostile states that were based on existing divisions between left-wing and right-wing Koreans and which aligned themselves with the opposing sides in the Cold War. By the time the occupying superpowers withdrew their forces in 1948 and 1949, a low-level conflict was already under way between communist and anticommunist Koreans in the south, and in June 1950, when communist-led north Korea attempted to liberate the south by military means, the conflict erupted into the three-year-long Korean War. The Korean War, with its enormous human and material costs, was never formally declared and has never formally been concluded. The shooting stopped with an armistice in July 1953, which established a cease-fire line roughly along the 38th parallel where the fighting started in 1950. The warring armies were separated by a "demilitarized" strip across the peninsula, and today, more than forty years later, 1.5 million soldiers (including 37,000 from the United States) still face each other, armed to the teeth, across that strip.

The existing rivalry between left and right within Korea thus played into the rivalry between the superpowers in the Cold War, who undertook to support and develop the rival Korean states as part of the worldwide competition between communism and democratic capitalism. The longevity of the Cold War overcame early hopes for Korean reunification and established powerful vested interests in the military confrontation between north and south Korea. These interests, added to the bitter experience of the Korean people during the Korean War era, created an almost insoluble problem for the Korean people. By 1996, though there had been numerous hopeful turns, there was little indication of how, and on what terms, Korea could ever be reunited, in spite of what could be gained if reunification were to occur. Even in their tense and divided condition, the two Korean states have made impressive progress toward the realization of a modern industrial society. A reunited Korea would be among the twenty most populous countries in the world. Its people would already be known as some of the hardest working, most productive people in the world. Their economy would rank in the world's top twelve and their military forces would establish them as a top regional power, leaving behind as a distant memory the time when Korea was known as a "shrimp among whales."

Though the Cold War has dominated the circumstances of recent Korean history, another kind of confrontation has been working itself out: the clash between modernity and tradition, between a new urban industrialized society and an old rural agrarian one, between the new demands for political participation and social justice and the old hierarchical, authoritarian order. Understanding this problem in all its complexity, as well as appreciating Korea's progress, requires some knowledge of Korean history and social and political background.

This introductory chapter briefly reviews the geography, resources, and people of the Korean peninsula. It then touches upon the problems arising out of Korean history, culture, politics, economics, and international relations—topics that are examined in greater detail in the rest of the book.

Basic Geographic Facts

The Korean peninsula juts southward from the Eurasian land mass between Russian Siberia and Chinese Manchuria. As nineteenth-century strategists used to say, it points "like a dagger at the heart of Japan" (Figure 1.1). The national territory, now as for many centuries past, includes a slice of the Asian mainland—a reminder of ancient Korean domains in parts of Manchuria (see frontispiece).1

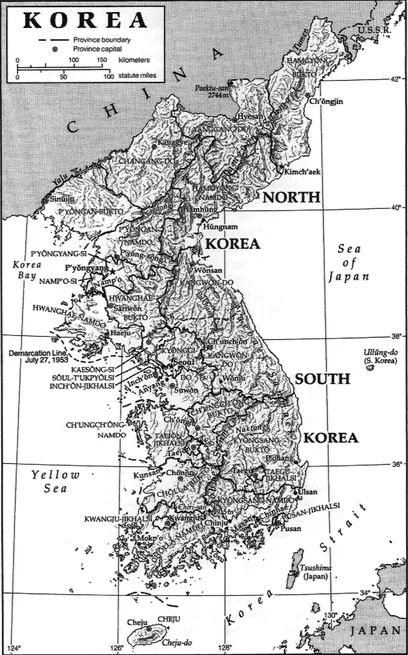

Korea's shape has been compared by Korean scholars to a rabbit, whose ears touch Siberia at the 43d parallel in the northeast; whose legs paddle in the Yellow Sea on the west, and whose backbone is the great T'aebaek mountain range along the east coast (Figure 1.2). The semitropical, volcanic Cheju Island, which is just above the 33d parallel south of the peninsula, could be regarded as the rabbit's slightly misplaced cottontail.

The 1,025-kilometer (636-mile) Korean boundary with China is formed by two rivers, the Yalu to the west and the Tumen to the east; they rise near the fabled 9,000-foot Mt. Paektu ("White-Head Mountain" in Korean; "Changpai-shan," or "Ever-White Mountain" in Chinese), the highest point in Korea, and flow through rugged mountains into the seas on either side of the peninsula. The last 16 kilometers (about 11 miles) of the Tumen's course separate Korea from Russia's Mar

FIGURE 1.1 Korea in its East Asian setting (map by Carl Mehler)

FIGURE 1.2 Physical-political map of Korea (map by Carl Mehler)

itime Province. Japan, to the east, is separated from Korea by the East Sea (Sea of Japan) and by the 100-kilometer (60-mile) width of the Korea Strait (Strait of Tsushima). The Japanese island of Tsushima, in the middle of the strait, is about 35 kilometers (20 miles) from the nearest point in Korea.

The de facto boundary between the two Korean states is the Military Demarcation Line established by the Armistice Agreement of 1953, which replaced the division at the 38th parallel agreed to by the United States and the Soviet Union in 1945. The boundary lies in the middle of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), 4 kilometers (2.4 miles) wide.2 Traced from west to east, the line begins in the Han River estuary on the west coast, runs just south of the city of Kaesong (ancient capital of the Koryo Dynasty), and then extends generally east-northeast to the East Sea. The narrow triangular area above the 38th parallel thus added to the south by the Armistice Agreement is technically under United Nations Command jurisdiction, but in fact has become part of south Korea.

The total area of north and south Korea is 220,847 square kilometers (about 85,300 square miles). The Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) in the north has 122,370 square kilometers (47,300 square miles), or 55 percent of the total, and the Republic of Korea (ROK) in the south has 98,477 square kilometers (38,000 square miles). The whole of Korea is about as large as the U.S. state of Minnesota and slightly smaller than the United Kingdom.

Korea is very mountainous; the Koreans themselves speak of their three thousand rp of beautiful rivers and mountains" in song and story and often go to the mountains for meditation or enjoyment. The dominant T'aebaek range (the "rabbit's" backbone) has a series of spurs, mostly running southwestward, that cut the peninsula into narrow valleys and alluvial plains. In the northeast, the picture is more complicated; it includes a range of extinct volcanoes from Mt. Paektu southeastward to the East Sea (Sea of Japan). About 16 percent of the land in the north and 20 percent in the south is flat enough for grain and vegetable crops.

The mountains of Korea are not very high for the most part, but they are quite steep and form a dominant feature of the landscape almost everywhere in the country The so-called Diamond Mountains in southeastern north Korea, a very striking area of sharp, rocky pinnacles, have long been a tourist attraction. For the most part, Korean mountains are nonvolcanic granite of great age, but two of the three highest peaks in the country—Paektu on the Manchurian border in the extreme north and Mt. Halla on Cheju Island in the extreme south—are extinct volcanoes with lakes in their craters. There are a few other volcanic peaks in the north, none of them active. Korea, unlike Japan, does not lie on a major fault line in the earth's crust, so earthquakes are not a problem.

Like the rest of East Asia, Korea has a monsoon climate characterized by cold, dry winters and warm, humid summers. The Korean spring and autumn are very pleasant, with generally fair weather and moderate, gradually changing temperatures. Rainfall varies between 76 and 102 centimeters (30 and 40 inches) per year in the south (somewhat less in the north) of which about half comes in June, July, and August. For comparison, in the continental United States, annual rainfall is 107 centimeters (42 inches) in New York City, 79 centimeters (31 inches) in Oklahoma City, and 51 centimeters (20 inches) in San Francisco.

Southern Korea is warmed by the Japan Current, somewhat as the eastern U.S. seaboard is warmed by the Gulf Stream; for this and other reasons, southwestern Korea and the adjacent island-province of Cheju are semitropical and have more rainfall. Mean daily temperatures in the extreme north range between — 18° Celsius (0° Fahrenheit) in January and 20°C (68°F) in August; in the extreme south (Cheju Island), between 3°C (34°F) in January and 27°C (81 "F) in August. In Seoul, near the center of the peninsula, the range is from —6°C (21°F) to 26°C (79°F). Considerably higher and lower temperatures are not uncommon. For comparison, average New York City temperature in January is 0°C (32°F); in July, 25°C (76°F).

Korea's rivers—except for the Yalu on the border with China and the Taedong River near Pyongyang, capital of north Korea—are generally too small, silted, and variable in flow to be practical for navigation. Some of them—particularly in north Korea—have hydroelectric potential; but for this purpose, too, their variation in flow, because of the concentration of rainfall in the summer months, reduces their utility. Most of them rise in the eastern mountain chain and flow west to the Yellow Sea or south to the Korea Strait. The Yalu, with a length of 790 kilometers (490 miles), is Korea's longest river and is navigable for most of its length. Other north Korean rivers are the Tumen (exceptional in flowing northeast and southeast), 521 kilometers (323 miles) long, of which only the seaward one-sixth is navigable; and the Taedong, 397 kilometers (246 miles), which flows through the capital city of Pyongyang and is navigable for about three-fifths of its length.

South Korean rivers include the Naktong (defense line of the beleaguered UN forces in the summer of 1950), 521 kilometers (323 miles) long, and the Somjin 203 kilometers (126 miles), both of which flow south to the Korea Strait; the Han, 514 kilometers (319 miles), which flows past Seoul; and the Kum, 401 kilometers (249 miles). Other, shorter rivers are the Yongsan, flowing southwest into the Yellow Sea at the southwestern port of Mokp'o; a tributary of the Han, the Pukhan, which rises in north Korea; and the Imjin, also rising in north Korea, which flows for part of its length along the Demilitarized Zone separating the two Korean states.

On Korea's east coast, the mountains rise almost directly from the sea. There is a narrow coastal strip in some areas, and there are a few harbors at north Korean cities such as Chongjin, Kimchaek, Hamhung, and Wonsan and south Korean cities like Kangnung and Ulsan. Pusan, perhaps the best port on the peninsula, marks the eastern beginning of the southern coastline along the Korea Strait. On the west, the coastline is deeply indented, with hundreds of islands and islets; a nine-meter (thirty-foot) differential between high and low tide causes mud flats, treacherous currents, and other navigational problems. The ports of Sinuiju and Namp'o, in north Korea, and Inch'on, Kunsan, and Mokp'o, in south Korea, are at or near the mouths of rivers ( the Yalu, Taedong, Han, Kum, and Yongsan, respectively); at Namp'o, in north Korea, and Inch'on, in south Korea, giant locks maintain a constant water level within the port area. Along the south coast there are ports at Yosu, Chinju, and Masan.

From the strategic point of view, Korean geography offers something of the same defensive advantage against ground forces as does Switzerland.

The majority of the boundary is seacoast, much of which is not practical for landing large ships. The land boundary with China is mostly in difficult, mountainous terrain, and the flatter coastal approaches are cut by the wide Yalu River. A similar coastal approach from the Soviet Union is cut by the somewhat narrower Tumen River. Roads within Korea wind between mountains and over passes, where defensive action is relatively easy. However, there are three major invasion corridors across central Korea: one near Ch'orwon in the middle of the peninsula, the other two in the west, where the bulk of the south Korean defense is concentrated.

From the air, Korea is as vulnerable as any country, and its internal communication lines, concentrated as they are in narrow valleys and often bounded (in summer) by soggy rice fields, could be readily interdicted by bombardment. South Korea's greatest geographical vulnerability is the difficulty of supply from any source other than the two hostile neighboring continental powers, China and the Soviet Union. The sea lanes are open to attack from either air or water.

Resources

Although Korea was essentially self-sufficient as an agrarian subsistence economy until the twentieth century, its development prospects as an independent state depend upon world trade. This is even more true of the two present divided states— particularly south Korea. The peninsula as a whole is only moderately endowed with natural resources; in both north and south, the principal asset is an educated, motivated, and able work force. The north has far more natural resources than the south; the rugged northern mountains contain coal (chiefly a poor grade of anthracite), iron ore, and a variety of nonferrous minerals, including tungsten, lead, copper, zinc, gold, silver, and manganese. Other ores include graphite, apatite, fluorite, barite, limestone, and talc. There are extensive hydroelectric power resources, particularly along the Yalu, Tumen, and Taedong rivers, as well as smaller streams. (Since the Yalu and Tumen rivers are on Korea's northern border, their resources must be shared with China.) Only about one-sixth of the mountainous north Korean terrain is suitable for cultivated crops, and the climate is relatively harsh. Nevertheless, coastal lowlands, particularly in the west, produce rice as well as other grains; elsewhere, corn, wheat, millet, and soybeans are grown. There are rich timber reserves and extensive orchards. Livestock grazing is also possible in the upland areas.

The south is the traditional rice bowl of Korea, with somewhat greater rainfall, warmer climate, and a slightly larger expanse of flat terrain than the north. These same factors make for a higher population density in the south—much increased by in-migration since World War II—which offsets the agricultural advantage. There are some of the same kinds of minerals as in the north but in less desirable deposits and smaller quantities, coming nowhere near the requirements of an industrial economy. The only significant reserves are tungsten, graphite, and limestone. Offshore oil possibilities in the Yellow Sea and on the continental shelf between Korea and Japan have so far yielded nothing but are being explored by south Korea, to the extent that the competing interests of Japan and China permit. By the 1950s, south Korea was virtually deforested; a vigorous reforestation program has brought a surprising recovery, but indigenous timber resources can never approach consumption requirements.

People

In 1994, south Korea's population stood at 44,453,000, an increase of 2.7 percent since the census of 1990 at an annual rate of 0.9 percent. The Republic of Korea was thus the third most densely populated country in the world, with 447 persons per square kilometer (1,176 per square mile). The capital city, Seoul, accounted for almost a quarter of this number (10,925,000), with a staggering density of 18,933 people per square kilometer (47,500 per square mile, equivalent to a square of land 7.4 meters [23 feet] on a side per person). Aside from Seoul, there were five other cities with over 1 million people: Pusan, the major southeastern port, with 3,798,000; Taegu, in the southeastern agricultural region, with 2,229,000; Inch'on, the major west-coast port near Seoul, with 1,817,000; Kwangju, in the southwest, with 1,139,000, and Taejon, in central south Korea, with 1,049,000 (population figures from the 1990 census). Cities of more than 50,000 people accounted for 75 percent of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Preface to Third Edition

- Preface to First Edition

- Acknowledgments

- A Note on Korean Names

- 1 Introduction: Land, People, Problems

- 2 Historical Background

- 3 Korean Society and Culture

- 4 Politics and Government of the Republic of Korea (South Korea)

- 5 Politics and Government of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea)

- 6 Economics

- 7 Korean National Security and Foreign Relations

- 8 The Problem of Korean Reunification

- Appendix A: Glossary

- Appendix B: The Korean Language and Its Romanization

- Appendix C: Korean Studies Reading List

- About the Book, the Author, and the Editor

- Index