![]()

~0~

Looking Back

Every story has more than one beginning. It’s up to the storyteller to decide which beginning to choose. The story of World War II arguably began with the German blitzkrieg of Poland, or perhaps it really began with the Treaty of Versailles and the severe economic depression that followed. Some storytellers might go back even further into the history of Europe and of the Jews to find the basis of the events that followed. Still others might start with the saga of an obscure failed artist who somehow becomes one of the most powerful people of the 20th Century.

This book is the prequel to Game of X Vol 1. It is about Microsoft, its culture and its slow evolution as a game company. It is about the people who enabled that evolution, both artistically and technically. It is about unlikely events, accidental succcesses, and catastrophic failures. It is also about visionairies and people who asked permission after. It is about big events, and small technological details. It’s about “very smart people” who could disagree, sometimes heatedly.

The accounts I have related in this book are true to the best of my knowledge and are based primarily on interviews with people directly involved. Whenever possible, I interviewed people with opposing views, although that was not always possible.

There are sections of this book about the double face of the Developer Relations Group, who on the one hand were fully dedicated to supporting developers for Microsoft’s platforms, and on the other hand often used devious and manipulative practices—internally to accomplish their goals, and externally to cause grief to Microsoft’s rivals.

This book is about Microsoft and the internal and external drama that led to its adoption of games. There were unlikely heroes who did not wield osten sible power, but who changed the course of history nonetheless. And there are monsters in this story—like IBM and Apple and even Microsoft itself—and often a kind of good and evil dichotomy. But mostly this story is about grey areas where absolute good and evil are debatable and based on individual perspectives, and in some cases, its characters can be seen as both heroes and villains at the same time.

Stepping back to the early 1990s, nobody—and I mean nobody—would have bet that Microsoft would one day become a major developer of video game console systems. At the time, Japanese powerhouses Nintendo and Sega were duking it out over who could sell more millions of consoles and engage the most players with characters like Mario, Link and Sonic the Hedgehog. Microsoft was DOS and early Windows. They were tech, operating systems and a budding supplier of business applications. And in that context, something as completely divergent as games didn’t just happen by accident. If you follow a series of events within and outside of Microsoft, along with some tectonic cultural and technological events within the company, it becomes clear that one thing led to another, and to another, and ultimately to Xbox. And so, looking at it through the lens of history, it becomes clear that the Xbox story has several beginnings, depending on how you tell it. The true beginnings of Xbox could be attributed to events that took place in a boardroom in the late 1990s, but in order to understand how and why Microsoft ultimately took the highly improbable step of creating a video game console, it helps to look back at Microsoft’s surprisingly long history with games, as well as the culture of Microsoft, its internal and external battles, and the efforts of small, comparatively powerless groups of people, often working under the radar of the massive organism they inhabited.

Game of X: The Prequel, is the beginning of the long road to Xbox.

![]()

~1~

Microsoft Always Had Games

Games are inevitable. People play games. Even animals play games. Pick up a rock and you can make a game with it. Add a stick and you have more game possibilities. It’s just natural for human beings to invent ways to play.

Pretty much as soon as there were computers, there were computer games. Games like Colossal Cave: Adventure and Star Trek, the whole PLATO system, and many others were created on huge mainframe computers, which only large corporations and universities owned. There was no game industry. There were no game companies as we know them today. But there were games.

The first home computers were game machines. Pong was essentially a single-purpose computer, as was the Odyssey. Over time, game machines became more sophisticated, and more general home computers began to appear—the TRS-80, Commodore PET, Altair kits and others. Early home computers weren’t great game platforms, but they always had games.

The first home computers to achieve widespread popularity, the Apple II, Commodore’s VIC-20 and C-64, and the Atari 400 and 800 systems boasted full color displays. This crop of early home computers allowed users to do real work as well as play games, but games proliferated on them, while productivity was hampered by the limitations of the systems themselves and the slow evolution of technology. For instance, at the beginning, the Apple II and Commodore systems relied upon slow, linear tape drives to load and store data. Floppy drives eventually appeared, but during the early years there was no such thing as a hard drive, and memory was counted in bytes, not kilobytes, megabytes or gigabytes. They also printed text all in caps on lines only 40 characters wide. (I wrote my first book using an Apple II with all caps, 40 character lines, using a black and white TV as a monitor. Talk about headaches.)

One game-changing productivity innovation appeared first on the Apple II—VisiCalc, the first real spreadsheet. It might seem hard to imagine that something as utilitarian as a spreadsheet program could revolutionize the world of computers, but VisiCalc was a wonder in its time. It was a very sophisticated toy in some ways, and a major empowerment to businesses and individuals at the same time.

Then came the giant—Big Blue. IBM was a huge, respected, and very serious company. They didn’t make games. They made giant computers, and they were the dominant brand in the mainframe and business world. They were International Business Machines, with emphasis on business.

So when IBM introduced their first home computer, it was a big hairy deal. And when Lotus introduced Lotus 1-2-3, a spreadsheet even more powerful than VisiCalc, the combination rocked the world. And that’s where Microsoft first appears in the story, because they provided the operating system for the IBM PC. The Disk Operating System. DOS. The story of how Bill Gates managed to secure the operating system deal with IBM has been told many times and I won’t go into detail about it here. But this is where the Microsoft story begins.

The effect of the IBM PC combined with Lotus 1-2-3 can’t be overstated. They took the revolution in personal computers and made it legit. They made it business. And they made Microsoft rich, even though they were still small and nowhere near as important as Big Blue.

The First Game

Chronologically, Microsoft’s first game was an unlicensed, but mostly faithful to the original version of Will Crowther and Don Woods’ Colossal Caves: Adventure text-based game for the TRS-80, published in 1979 and later ported to Apple II and the brand-new IBM PC in 1981. The game was part of a new Consumer Products Division that Microsoft formed in 1979 under Vern Rayburn, one of the earliest Microsoft hires. But the story is even more convoluted, and it starts with an argument between Gordon Letwin and Bill Gates.

Letwin had written a disk operating system, H-DOS, for the Heathkit H8 and also his own version of BASIC. But then a very young Bill Gates showed up at Heath Company and started working to convince them to adopt Microsoft’s product. Letwin challenged Gates, pointing out some differences between their products. One of the key features he brought up was that his version would immediately check syntax if you entered a bad line of code, where Microsoft’s product didn’t. Stuff like that. Gates is later quoted as saying, “Anyway, he was being very sarcastic about that, telling me how dumb that was.”

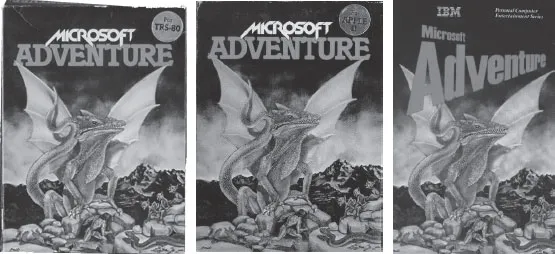

Three versions of Microsoft Adventure—TRS-80, Apple II, IBM PC.

Heath decided to implement Microsoft BASIC instead of Letwin’s version, but in typical Bill Gates fashion, he later hired Letwin, apparently valuing the man’s talent more than his tact. And it was Letwin who produced Microsoft’s first game. Technically proficient, he found a way to extract the content of the original Colossal Caves: Adventure code from the original FORTRAN, and recreate it with only a few intentional changes, mostly in jokes for programers and some simplication of puzzles. He also solved several technical problems with memory and code access by using a memory expander and random access, at the time very expensive, floppy disk to load and access the games, instead of cassette, which was the most common way of loading games like Scott Adams’ series of very popular text adventures.

Microsoft Adventure was never licenced or authorized, but Crowther and Woods never sought any credit or royalties to the game, and so Microsoft was never challenged in their use of the game.

Microsoft Flight Simulator

The game people remember as Microsoft’s first official “game” was Flight Simulator. Originally developed by Bruce Artwick and his partner Stu Moment, and released in late in 1979*, it first appeared on the Apple II and was published by their company, SubLOGIC. An improved version was licensed to Microsoft and was released late in 1982. Although Flight Simulator was not technically a game but a simulation of flight, it did include both a crop-dusting mode and a legitimate game called World War I Ace where you could dogfight while flying a Sopwith Camel.

According to at least one source, Microsoft and IBM both tried to get the Flight Simulator license, but Artwick chose Microsoft. The same (unverified) source also states that Microsoft’s 18th employee, Vern Raburn, was Artwick’s main contact. Although PC version was released as Microsoft Flight Simulator in 1982, it was still developed by SubLOGIC until 1988, which is when Artwick left and founded a new company, BAO (Bruce Artwick Organization), taking Flight Simultator with him.

Flight Simulator was very successful before the Microsoft deal, having sold well on a number of platforms, and the Microsoft version remained consistently profitable for several deccades. By the end of 1999 it had sold more than 21 million copies. Fight Simulator also set a Guinness world record as the longest running video game series (more than 32 years) as of September 2012.

Back in 1982, Microsoft was growing quickly, largely because its lucrative deal with IBM, but they were still in some ways figuring out what they wanted to become, other than the dominant force in the microcomputer industry. So it’s not clear how Flight Simulator figured into their plans, which had, in addition to their operating systems, featured forays into hardware peripherals like the Z-80 SoftCard, an upcoming computer of their own called MSX, and their first mouse; applications such as an early version of Word; and even a book publishing division.

Why, then, did Microsoft acquire the Flight Simulator license? I haven’t found anyone who can answer that question. Perhaps it was an experiment. Possibly someone just saw it as a successful product on other systems, and decided to acquire it as yet another direction for the fast-expanding company to enter into. What is is clear in retrospect is that publishing Microsoft Flight Simulator was not the start of a grand plan to become a major player in the computer game field.

The Added Benefit of Flight Sim

Whatever the reason for having Flight Simulator, it ended up serving a purpose that most people would not have guessed. According to Russ Glaeser, a veteran of both BAO and Microsoft’s ACES studio formed around Flight Simulator, “one of the interesting things about early flightsim was that it basically just went around DOS. It was written in one hundred percent assembly language. It just hit the hardware directly. And it was such a good test of Intel compatibility that that’s what they used it for. That was one of their tests to see if new chips coming out were Intel compatible.” In fact, Flight Simulator was such a good predictor of compatibility that it was used in testing all the way until Windows 7.

Jon Solon had moved from Minneapolis to Seattle largely because of his love of hang gliding, but as an early hire at Microsoft, he began in the applications test division. After doing some testing on Project and Word, he had the opportunity to test Flight Simulator 3 by virtue not only of his hang gliding experience, but because he was also a licensed pilot.

Solon and Artwick were partially responsible for turning Flight Simulator into a Windows testing application. He says, “It was rather dramatic in the sense that Bruce Artwick and I had benchmarked the performance of the early Windows, and we basically submitted a memo to Bill Gates and Brad Allchin, Silverberg—all the main Windows folks—and said that Flight Simulator version 5 and Space Simulator version 1 would NOT be Windows products, and here’s why.” In the memo, they demonstrated the constraits involved in writing to the screen quickly, especially in aerial maneuvers such as banking the aircraft or even moving quickly through the galaxy in Space Simulator. Instead of Windows, he says, “we had to do it in DOS using expanded memory - not extended memory, but expanded.”

Solon says with pride that he and his team were responsible for nudging the engineering team to address Window’s deficiencies in graphics. They would not be the last ones to point this out, but they may possibly have been the first.

*Part II of this volume focuses heavily on Windows’ ability to support games and the story behind the technology that allowed fast-paced games to excel on PCs, despite Windows.)

The Purchase

On December 12, 1995, Microsoft announced the purchase of BAO, stating “Under the terms of the agreement, Artwick will consult with Microsoft in the design and development of new titles while the majority of BAO’s development team will relocate to Microsoft’s Redmond campus.”

Glaeser was one of the BAO developers who relocated. “We were in the process of working on Flightsim 95 when they announced to us that we were all going to be moving to Seattle. At that time we were located in Champaign, which is 120 miles outside of Chicago. They did the transition in a very strange way. They didn’t want to be disruptive, and by not being disruptive, they made it way worse. They basically didn’t want to bring the whole team down for 2 weeks while everybody moved, so they just took one or two people and moved them, one at a time, which meant that some part of the team was unavailable for 2 weeks. And that went on for 6 months.” This was only the first of several awkward transitions of companies acquired by Microsoft over the years. More examples later…

Eventually, things got sorted out and the ACES division of Microsoft continued to develop and consistently improve Flight Simulator until the studio was closed down in 2012.

Microsoft released one other DOS game in 1982 called Olympic Decathlon (also known as Microsoft Decathlon), which had originally appeared on the TRS-80 in 1980 and th...