- 260 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This is the first book to tackle all the issues relating to timber decay. It presents the facts and explores timber decay problems through case studies. These are illustrated with clear self-explanatory photographs for the reader to use as a diagnostic aid. Section 1 discusses timber as a living material, Section 2 deals with decay organisms and their habitat requirements. Section 3 moves on to the building as an environment for timber and discusses the ways in which wood responds to moisture change. Section 4 ends with an approach to timber decay which integrates knowledge on the decay organism, its requirements and natural predators with appropriate and targeted chemical treatments.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Timber Decay in Buildings by Brian Ridout in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Architecture GeneralPART ONE

Nature of Wood

CHAPTER ONE

Origins and durability of building timber

1.1 Introduction

If I discover a few beetle emergence holes in the rafters of my roof, then I have ‘woodworm’ damage in my house. But what are the implications? The beetle grubs (larvae) eat wood, and the roof is mostly wood. Will the beetles spread until all the timbers have been destroyed? The answer to this question is usually no, but if we are to understand why, we must unravel the story of how wood is constructed, and how the woody material is organized to form a tree.

If we do this then we will find that wood is not the uniform material it appears to be. A plank of European redwood, for example, will contain a variety of substances distributed in a variety of microscopic cells. It is these variations that initially define the potential damage that decay organisms could cause, and thus give the wood whatever natural durability it might possess.

1.2 Structural polymers

The natural durability of building timber is determined by the properties and age of the tree from which it originally came. Healthy trees are living structures in harmony with their environment, and every element of that harmony, whether structural or chemical, affects the quality and durability of the converted timber.

A tree, like all living plant material, is largely a factory for the production of structural and consumable sugars. The bulk of the tree ultimately derives from the reaction of carbon dioxide in the air with water from the air and soil to produce sugar (carbohydrate). This process is fuelled by the radiant energy in sunlight together with agents in the plant that capture light energy, and is called photosynthesis. The sugar-producing reactions may be summarized by the simple equation:

carbon dioxide + water = carbohydrate + water + oxygen

Glucose, a simple sugar, is a the end product, as shown in Figure 1.1. This interesting molecule forms the basic building block for a variety of useful substances. If glucose molecules are assembled all in the same plane, starch is produced:

glucose + glucose + glucose + glucose = starch

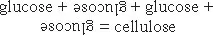

Starch is readily broken down again for energy, and forms an easily consumable storage product for plants. If glucose molecules are assembled so that alternate units are inverted, cellulose is formed:

Although constructed from precisely the same molecules as starch, cellulose has entirely different properties. It is very stable and forms straight chains which average between 8000 and 10000 glucose molecules in length (Siau, 1995). Cellulose forms about 40–50% of wood and is largely responsible for the strength within the cell wall (Goring and Timell, 1962).

Figure 1.1 The production of sugars as building blocks, and the construction of starch and cellulose.

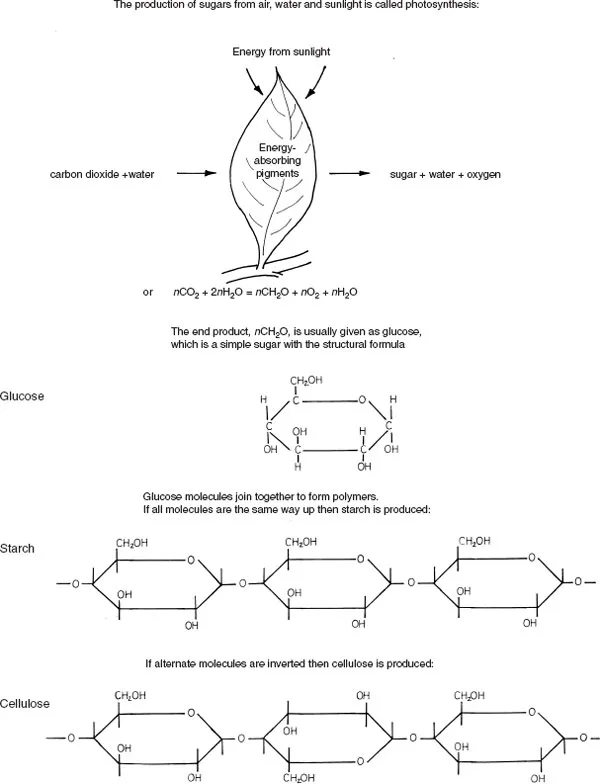

Once the plant has managed to incorporate carbon from the atmosphere then the formation of a wide range of sugars (carbohydrates) and other organic products becomes possible. A second structural polymer, hemicellulose, which differs somewhat between hardwoods and softwoods, is also formed from sugars. The molecular chains of hemicellulose are shorter than those of cellulose, and are frequently branched. Hemicellulose, which commonly forms about 20–30% of softwoods and 25–40% of hardwoods, is responsible for elasticity (Siau, 1984).

Sugars also start the formation of an immensely complex series of molecules known as lignin. Lignin, which is very stable and crucial to durability, is the third structural component in wood. Fengel and Wegener (1989) believe that it was the incorporation of lignin into and around cell walls that gave plants the mechanical strength to colonize the earth’s surface. Hardwoods tend to have less lignin (20–25%) than softwoods (25–30%); (Siau, 1995).

Lignin is constructed from different combinations of three phenolic molecules (Figure 1.2) which occur in different proportions in hardwoods and softwoods (Adler, 1977). Their relative proportions affect the properties of the lignin, and in general lignins from hardwoods are weaker and more easily degraded than those from softwoods. This feature, as will be discussed later, influences timber’s vulnerability to different kinds of fungi.

1.3 Cell wall

We have seen that wood is mainly composed of three complex molecules: cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin. These three components together form the wall of the cell, the fundamental unit of the tree. It is the arrangement and orientation of these three components that give wood the ability to support tall trees.

The basic cellulose component of a cell wall at the molecular level is usually called a microfibril, although smaller, elementary fibrils have been described (Mühlethaler, 1960). Microfibrils are about 10–30 nm in diameter (1 nm = 1 nanometre = one millionth of a millimetre). Each consists of bundles of cellulose chains arranged at various angles along the long axis of the microfibril. Some regions of the microfibril are known to be crystalline, and some amorphous, but there is no generally accepted theory regarding internal molecular organization. It is usually considered that the hemicellulose encrusts the cellulose microfibrils (Tsoumis, 1991), but no doubt the exact arrangements will prove to be variable and complex when they are finally unravelled.

Figure 1.2 (a) Mixed sugars produce branched chain polymers called hemicelluloses. (b) Photosynthesis also commences the production of three phenoliz building blocks that form complex polymers called lignin.

The generalized manner in which the three complex structural substances are arranged to construct the cells has a significant bearing on decay. Each decay organism attacks celluloses and lignin in its own way, and the final results of decay will depend on the way in which the cell structure is organized.

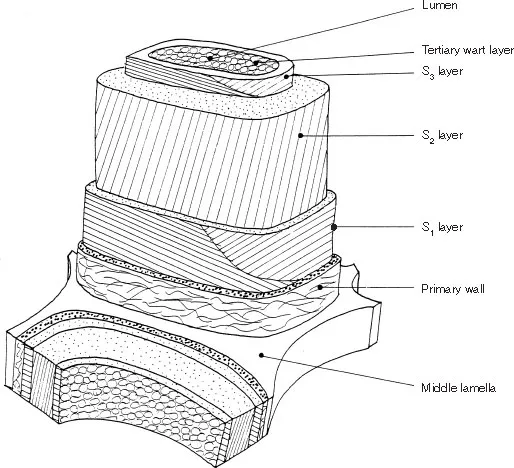

An array of powerful modern laboratory techniques has allowed this organization to be assessed. The cell wall, which is largely composed of cellulose microfibrils, is constructed from two, or sometimes three, distinct layers (Figure 1.3): the outside or primary wall, the secondary wall and sometimes an innermost tertiary wall or wart layer, which is next to the lumen or hollow interior of the cell. The thickness and arrangement of these layers has been investigated in several coniferous woods (Saiki, 1970).

Primary wall (P)

A very thin wall constructed from a loose weave of microfibrils with limited organized orientation. This is the first wall produced, and its organization controls the expansion of the juvenile cell. It is bounded on its outer side by the middle lamella, a lignin-rich matrix between the cells.

Secondary wall (S)

This layer forms the bulk of the cell wall, and close investigation reveals two to three groups of laminations that differ in the orientation of their closely packed microfibrils.

S1 layer

This thin layer is usually indistinguishable under a microscope from the primary wall, with which it is closely associated. It consists of 4–6 laminations (lamellae), each of which possesses an alternating left-hand and right-hand spiral arrangement of microfibrils across the transverse axis of the cell. The result produces a crossed texture. This layer usually becomes encrusted with lignin.

Figure 1.3 Diagram of cell-wall layers and the orientation of microfibrils. (Redrawn from Tsoumis, 1991.)

S2 layer

The S2 layer is the thickest within the cell wall, and may consist of 30–150 lamellae. Microfibrils are densely packed and run approximately parallel to the cell axis in mature wood.

S3 layer

Usually thinner than the S1 layer and frequently absent altogether, this layer consists of about six lamellae with microfibrils alternating in their direction of orientation, which mostly approaches the transverse axis of the cell.

Tertiary/wart layer

Microfibrils are arranged in a gentle slope as in S1 and S3, but the microfibrils are not strictly parallel. The interior surface of this wall becomes covered with warts in many types of timber. Warts are mostly formed from lignin.

Between the cells lies a layer of material called the middle lamella (Figure 1.3). Analysis has shown that it is composed mostly of lignin.

A considerable proportion of the lignin in wood therefore forms a matrix between the cells, whereas most of the cellulose is within the thick secondary walls. Hemicellulose encrusts the microfibrils, and tends to replace cellulose in the thinner walls. The proportions of the three structural polymers in each element of the cell wall will vary considerably from tree to tree, across the thickness of the tree, and in earlywood and latewood.

The strength of timber is a function of all three components, but cellulose mostly confers strength in axial tension because of the orientation of microfibrils in the thick S2 layer, whereas the other layers, hemicellulose and lignin provide elasticity and strength in compression.

The arrangement of microfibrils within the secondary wall layers also affects the swelling properties of wet timber. The predominance of microfibrils orientated parallel to the long axis in the S2 layer restricts longitudinal swelling in mature wood, whereas transverse dimensional change, though substantially greater than longitudinal, is ultimately restrained by the transverse orientation of microfibrils in the S1, S3 and tertiary layers. These relationships are discussed further in Section 2.1 and Chapter 11.

Trees react to strain forces acting on stems, boughs and branches by forming reaction wood in the zones of compression or tension. These tissues differ chemically, physically and anatomically from each other, and from normal wood. Reaction wood forms only a small fraction of building timbers and will not be discussed further here.

1.4 Structure of wood

We have now seen how water and carbon dioxide react, using the energy from sunlight and energy-capturing molecules within the tree to form simple sugars, the building blocks that are assembled and modified to form the three structural polymers (cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin) which together constitute 97–99% of temperate zone woods and about 90% of tropical woods. The remaining few per cent are a wide variety of substances known collectively as extractives. These are of considerable significance and will be discussed further in Sections 1.5.2. and 11.12.

The three structural polymers are not randomly deployed, but are assembled into cells in a manner that maximizes tensile and compression strength for the tree, and restrains excessive swelling as a consequence of water absorption. Strength and the efficient conduction of liquids are of paramount importance in the organization of cells into a large and vigorously growing tree.

The tree must support its own weight, withstand adverse conditions, and convey water and nutrients to the highest branches. These exacting requirements cannot be satisfied at cell level alone, and specialized structures within the wood are required in order to maximize efficiency.

1.4.1 Softwoods and hardwoods

The terms ‘softwood’ and ‘hardwood’ are used extensively within the timber trade, and frequently lead to confusion. Softwood refers to the conifers, the needle-leafed or cone-bearing trees (for example pine and cedar), some of which provide quite hard timber. Hardwood is used to describe timber from the so-called broad-leafed trees (for example oak and mahogany) and includes species whose wood is in fact very soft. Nonetheless, the distinction between softwood from cone-bearing trees and hardwood from broad-leafed trees remains extremely useful.

The softwood trees are botanically known as gymnosperms (from the Greek: naked-seeded) because the seeds develop exposed on the surface of a cone scale. The gymnosperms living today are the representatives of a group that extends back in time for more than 300 million years (Sporne, 1965). Modern softwood trees are mostly restricted to regions where the climate is harsh and the soil is poor in nutrients. Their ability to sur...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Illustration acknowledgements

- Part 1: Nature of Wood

- Part 2: Agents of Decay and Traditional Treatments

- Part 3: Effects of the Building Environment on Timbers

- Part 4: Evolving a Philosophy for Timber Treatment

- Appendix A: Analytical approach to preservative treatment

- Appendix B: Dry rot case studies

- References and bibliography

- Index