- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book explains why the Iraq War took place, and the war's impacts on Iraq, the United States, the Middle East, and other nations around the world. It explores conflict's potential consequences for future rationales for war, foreign policy, the United Nations, and international law and justice.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Iraq War by James DeFronzo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Política y relaciones internacionales & Políticas de Oriente Medio. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Culture and History of Iraq

Ancient Mesopotamia to the British Mandate

Iraq within its current borders was created shortly after the end of World War I. Which peoples and territories to include or exclude from the new state were in great part decided with the interests of other countries in mind, especially Great Britain. Besides large oil and natural gas reserves, Iraq has rich agricultural lands, but internal and international conflict has often deprived the Iraqi people of fully and securely realizing and enjoying their country’s energy and agricultural potential.

The People and Land of Iraq

Great Britain, which occupied much of the former Ottoman Empire at the conclusion of World War I, combined three former Ottoman provinces—Mosul province in the north, Baghdad province in the center, and Basra province in the south—to constitute the new state of Iraq. Britain had earlier detached Kuwait from Basra province and later helped establish it as an independent state.

Approximately 168,754 square miles (437,072 square kilometers), Iraq is bounded by Kuwait and Saudi Arabia in the south, Jordan in the west, Syria in the northwest, Turkey in the north, and Iran in the east. It has access to the Persian Gulf through only two ports, Basra on the Shatt al-Arab (the Arab River), formed by the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, and Umm Qasr, which is located on the Persian Gulf where Iraq controls only about 36 miles (58 kilometers) of the coastline. Rain, except in the north of Iraq, falls almost exclusively during winter. Summers tend to be hot and dry with many cloudless days. The US CIA World Fact Book (2008a, 4) indicates that in 2008 Iraq’s population exceeded 28 million people. But as many as 2 million people may have fled Iraq in the aftermath of the US-led 2003 invasion.

The origin of the name “Iraq” is unclear. It may have been derived from the ancient Sumerian city of Uruk, once located in what is now southern Iraq. However, William Polk (2005: 32) suggests that it comes from the Persian expression erãgh, meaning “the lowlands.”

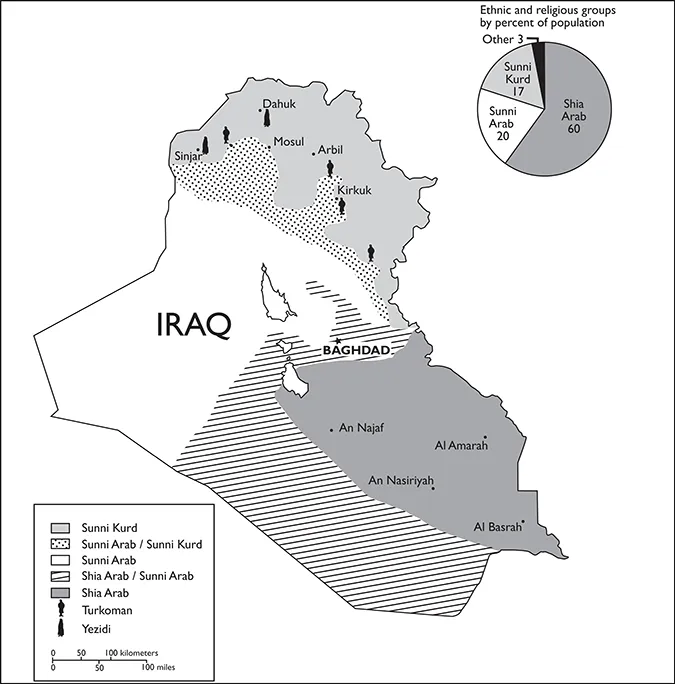

Map 1.1 Ethnoreligious Groups in Iraq

The population is estimated to be about 75 percent to 80 percent Arab, 15 percent to 20 percent Kurdish (residing mainly in the northeast in areas bordering Turkey and Iran), and about 5 percent other ethnic groups, such as Turkoman, Assyrian, Armenian, or Persian. About 97 percent of Iraq’s people are Muslim. An estimated 60 percent to 65 percent are Shia (predominantly in the south, but also the majority in the capital city, Baghdad), 32 percent to 37 percent are Sunni (mainly in central and northern Iraq), and 3 percent Christian or members of other faiths. Most Iraqi Arabs are Shia, but about 75 percent of Kurds are Sunni and 15 percent are Shia (Anderson and Stansfield 2004: 159). Baghdad has a population of over 5 million, the southeastern city of Basra more than 1.5 million, and in the north Mosul has more than 1 million and Kirkuk more than half a million.

The country’s diverse terrain and peoples are linked by the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. In the south near the confluence of the twin rivers are considerable wetland and marsh areas. Between the wetlands and Baghdad is the delta territory, home of the Sumerian and Babylonian civilizations of ancient Mesopotamia, a flat area where rain is scarce and farmlands are irrigated by river water. In the northeast the rugged mountains are inhabited almost exclusively by Kurds.

Ancient Civilizations

Mesopotamia is a Greek term meaning “the land between the two rivers.” But more generally Mesopotamia included virtually all the land bounded by the Persian Gulf on the south, the Zargos and Anti-Taurus mountains on the west and north, respectively, and the Arabian plateau on the southwest. This encompassed most of modern Iraq and parts of Syria and Turkey. Here the ancient Ubaidians, Sumerians, Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians created revolutionary innovations that greatly influenced the history of humankind, including farming, leading to the development of cities. The Babylonian king Hammurabi (1792–1750 BCE) created one of the first and most historically influential codifications of laws. By setting forth laws in writing, Hammurabi’s Code advanced civilization through state-enforced norms that provided uniformity and stability, and reflected a level of common interest that rulers could not arbitrarily ignore. Major contributions of Mesopotamian civilizations to the development of world society, including metalworking, the wheel, writing, and precise calendars, led some modern Iraqi leaders to foster pride in this heritage among the country’s diverse ethnic and religious groups in attempts to create a strong national identity.

Persian (Iranian) and Greek (Macedonian) Conquests

In 539 BCE, Cyrus of Persia conquered Babylonia. He was so enamored of the city of Babylon and its achievements that he decided to make it the capital of the Persian Empire and attempted to blend Babylonian and Persian cultures. When Alexander the Great defeated the Persian army and in 330 BCE entered Babylon, he, like Cyrus before him, conceived the idea of uniting cultures, but this time he attempted to unify the culture of the West, Greece, with the cultures of the East, Babylon and Persia. He apparently intended to make Babylon the capital of the world but died there in 323 BCE, after which his empire was subdivided among his top commanders. A new Persian force, the Parthians, captured Babylon in 144 BCE.

Traditional Forms of Social Organization and Authority

From Mesopotamian civilizations to modern Iraq, traditional forms of social organization have played significant roles in economics and politics: the family, the clan, and the tribe. Theoretically, blood relationships are the basis for all three. Family units encompass grandparents, aunts and uncles, and their children (first cousins). The clan (or subtribe) extends beyond the immediate family to include more distant relatives, such as second, third, and fourth cousins, whose existence and relationship to each person may be known to each member of the clan. But unlike the family, face-to-face interaction between clan members is generally more limited. In Iraqi Arab society, a clan often includes several extended family networks that trace their origin to a common father.

The concept of tribe generally refers to a set of clans (often four to six) that are united by a sense of blood kinship and the notion that all of the clans are descended from a common ancestor. In all forms of kinship-based organization, certain members of the kin network are recognized as leaders who have the right to exercise authority over other members. The leader of an Arab tribe is called a sheik, an Arabic word meaning “a man of old age.” Among the Shia, a tribal sheik often shares power with a religious leader. The tribal subculture typically emphasizes hospitality and courage. For many, tribal membership provides a sense of identity and a feeling of security, and tribal leaders are often called upon to mediate disputes. Tribalism among Iraq’s Kurdish population is similar, with tribal leaders referred to as aghas.

As strong central governments emerged in Iraq, providing police, legal frameworks, courts, and various forms of social assistance, the importance and influence of tribes and clans subsided. However, at times when the state lost legitimacy or its ability to provide essential services and security to its citizens, reliance on tribal networks tended to increase. Tribalism, along with ethnicity and religion, has been one of the three major dimensions of group identity in Iraq.

Islamic Iraq and the Shia-Sunni Split

The Prophet Muhammad, born in 571 in Mecca, described experiencing a vision of the angel Gabriel, through whom he received a series of messages to convey to humanity from the one true God. Muhammad’s associates assembled those messages into the holy book of Islam, the Quran (Koran). Islam spread rapidly in part because of its principle of social organization, superior to that of tribal society. By proclaiming that only one God existed and that all men who embraced Islam (the state of submission to God) became brothers, Muhammad laid the foundation for a form of social organization based on religious rather than blood kinship (Polk 2005: 38–39). As the “tribe” of Islam grew to include many thousands, it began to overwhelm resistance from traditional tribes. Thus it was not only Islam’s message but also the structure and character of the Islamic community that won adherents for the new faith.

The unexpected death of Muhammad in 632 created a leadership dilemma. Prominent Islamic figures elected Abu Bakr, the imam (Arabic for “stood in front”) who had led the daily prayers when Muhammad was unavailable, as the first caliph, or successor. In 656 Ali, the Prophet’s cousin and the husband of Fatima, the Prophet’s daughter, was elected the fourth caliph. Ali, whom many viewed as genuinely concerned about improving the lives of the poor, was faced with an increasingly fractured and internally conflicted Islamic community. In 661 he was assassinated.

Some Muslims proclaimed that Muhammad had actually chosen Ali to be his rightful successor. Furthermore, they believed that only the descendants of Ali and Fatima were to govern the Islamic community. Those who embraced this concept came to be known as the supporters or partisans of Ali, the Shiat Ali or, more simply, Shia. Shia Muslims referred to Ali and certain male descendants of Ali and Fatima, who they believed had the right to rule Islam, as imams (assigning this new meaning to the term other Muslims continued to use for the person who read the daily prayers). The imams were thought by the Shia to be infallible (incapable of religious error). Other Muslims rejected these ideas and believed instead that only the Quran, the most central element of the tradition, or Sunna, of Islam, was infallible. According to the Sunnis, religious leaders could only attempt to interpret the Quran to the faithful in the context of each historical era.

The martyrdom of Imam Hussein in 680 was of great significance for the Shia. Hussein was the grandson of the Prophet and was the third Shia imam after his father, Ali, and his older brother, Hassan. Following Ali’s death, the caliphate was assumed by Muawiya Abi Sufian, governor of Syria, who had opposed Ali. When Hussein refused to accept Yazid, Muawiya’s son, as the leader of Islam, Yazid’s army surrounded and killed Hussein and many of his companions in the Karbala desert of Iraq. Hussein’s death symbolized jihad (a struggle carried out for the sake of the Islamic community) and martyrdom (DeFronzo 2007: 277; Hussain 1985: 23–24) for Shia. The date of Imam Hussein’s death, Ashura, the tenth day of Muharram (the first month of the year of the Islamic calendar), is commemorated each year as a day of mourning when many Shia make a pilgrimage to the Imam Hussein shrine in Karbala. During the Saddam Hussein era, this event sometimes became an occasion for political protest.

Despite disagreement over succession to Muhammad, the Sunni and the Shia have similar sets of core beliefs. One significant disagreement, though, is that Shia believe the Quran supports the Nikah Mut’ah, or fixed-time marriages that people can enter into with the mutual understanding that the marriage will end on a predetermined date without the need for a divorce. Sunnis reject temporary marriage. Worldwide, the large majority of Muslims are Sunni, while about one-sixth are Shia.

Divisions developed among the Shia concerning how many infallible imams followed Muhammad. The large majority, dominant in Iraq and Iran, are Twelver Shias, who believe the twelfth and last imam vanished in 873, after which there was no longer an infallible leader of Islam. This situation will change, according to Twelver Shia, only when the “hidden imam,” or Mahdi, returns to the faithful. Until then Islamic scholars (mujtahid) are allowed to issue authoritative opinions. Since Karbala is located in southern Iraq, many people there embraced Shia Islam, and Karbala and Najaf became Shia holy cities. Iraqi political leaders often feared that in times of conflict with Iran, some among Iraq’s majority Shia population might side with their Iranian coreligionists.

Mongol Devastation and Ottoman Conquest

With a population of perhaps 1 million by the tenth century (Marr 2004: 5), Baghdad developed into the greatest center of Islamic civilization. But in 1258 Mongol armies captured the city, killing Caliph Mustasim and as many as 800,000 people (Polk 2005: 57). Baghdad was again devastated by the Mongols under Tamerlane in 1401 when tens of thousands more were killed (Al-Qazzaz 2006: 439). The Mongol invasions destroyed major Iraqi achievements in science and technology, and many of the country’s most brilliant residents.

Following the Mongol invasions, an Ottoman caliphate was eventually established in Istanbul. After the Persians occupied Baghdad in 1509, the Sunni Ottoman Empire responded in 1534 by seizing the city and later the rest of Meso potamia. The Ottomans remained in control, except for a brief period of Persian occupation in the seventeenth century, until the British invasion during World War I. What later would be established as Iraq after the end of World War I existed within the Ottoman Empire as three provinces (vilayats): Mosul (where many Kurds lived), Baghdad (which included much of what today is central and western Iraq), and Basra (southern Iraq and territory that became the separate country of Kuwait). The Sunni Ottomans preferred fellow Sunnis as administrators and military officers within Mesopotamia. Thus some four centuries of Ottoman rule firmly established Sunni Iraqis in leadership roles rather than the more numerous Shia.

World War I and the Arab Nationalist Revolt

A nationalist movement developed in the early twentieth century to free Arabs from Ottoman rule. When the Ottoman Empire entered World War I on the side of Germany against czarist Russia, Britain, and France, Ottoman conscription of Arabs (people who spoke the Arab language and identified with Arab culture) caused a surge in Arab nationalism.

Desperate for assistance in its war against Germany, Great Britain secretly entered into separate negotiations with several nations and groups over the future of the Ottoman Empire’s Arab territories. The British would later be accused of making conflicting but self-serving promises to several of their negotiation partners. Among the most important negotiations regarding Arab territories were the Hussein-McMahon Correspondence, the agreement with Abd al-Aziz abd al-Rahman al-Saud of the Najd region in Arabia, the British-French Sykes-Picot Agreement, and the Balfour Declaration, the British pledge to the Zionist movement to support a Jewish homeland.

The motive behind the Sykes-Picot Agreement of May 1916 seems obvious. Britain, desiring not to offend its ally, France, in the war with Germany and to avoid French interference with British postwar activities in the Middle East, developed a plan for Arab lands that would involve sharing them with the French. The Sykes-Picot Agreement divided the Ottoman Arab provinces between Britain and France, with the French getting Syria and Lebanon and the British getting Palestine and territories that would later become Jordan and Iraq.

The Balfour Declaration of November 2, 1917, committed Britain to creating a homeland for the Jews in largely Arab-populated Palestine. The British, in promising to gratify the aspirations of the international Zionist movement, were apparently hoping to win the support of the world Jewish community in Britain’s conflict with Germany. The British might have also hoped that the Balfour Declaration would appeal to Jewish leaders within Russia’s 1917 revolutionary government and influence them to keep Russia in the war, forcing Germany to continue to fight a two-front war (Ibrahim 2006: 75).

The agreement with Abd al-Aziz abd al-Rahman al-Saud stated that Britain would recognize al-Saud (future founder of the nation of Saudi Arabia) as the legitimate ruler of the huge Najd section of Arabia in return for al-Saud’s assistance against the Ottomans (Ibrahim 2006, 74). The role of al-Saud was significant in that his forces prevented the Ottoman army from receiving supplies through the Persian Gulf.

The British aimed to transform the Arab nationalist movement into a massive revolt again...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 Culture and History of Iraq

- 2 From the British Mandate to the 1958 Revolution

- 3 The Iraq Revolution and the Establishment of the Baathist Regime

- 4 Saddam Hussein, the Iranian Revolution, and the Iran–Iraq War

- 5 The Invasion of Kuwait and the 1991 Persian Gulf War

- 6 The Iraq War

- 7 Iraq in the Context of Previous US Interventions and the Vietnam War

- 8 Postinvasion Iraq

- 9 Counterinsurgency and US Corporate Presence

- 10 Impacts of the Iraq War

- Glossary

- Major Personalities

- Chronology of the Iraq War

- Selected Documentaries

- Index