1

Gulliver’s Travails

America and the World

If America’s current global predominance does not constitute unipolarity, then nothing ever will. The sources of American strength are so varied and so durable that the country now enjoys more freedom in its foreign policy choices than has any other power in modern history. Today the United States has no rival in any critical dimension of national power. There has never been a system of sovereign states that contained one state with this degree of dominance.

—Stephen Brooks and William Wohlforth,

Foreign Affairs, July/August 2002

Is the American empire mightier than any other in history, bestriding the globe as the Colossus was said to tower over the harbor of Rhodes? Or is this giant a Goliath, vast but vulnerable to a single slingshot from a diminutive, elusive foe? Might the United States in fact be more like Samson, eyeless in Gaza, chained by irreconcilable commitments in the Middle East [and elsewhere] and ultimately capable of only blind destruction?

—Niall Ferguson, Colossus, 2004

In March 2003, the United States sent more than one hundred thousand troops into Iraq and mounted a “shock and awe” aerial bombing campaign over Baghdad that was aimed at overthrowing Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein. Within a month, Hussein’s enormous statue in the center of the capital city was taken down, and by May 1 that same year, on board the USS Abraham Lincoln, President George W. Bush declared victory, with fewer than two hundred American combat fatalities suffered during what came to be known as the Second Persian Gulf War (dubbed “Operation Iraqi Freedom” by Washington). The war had gone well. Peace would be a different matter, however, with U.S. forces remaining bogged down in a brutal, protracted postwar insurgency through 2007, with little end in sight.

The Iraq conflict will eventually end, but the problems that gave rise to the intervention and the issues raised by the war are symptomatic of much larger phenomena that are likely to continue to preoccupy American foreign policymakers for much of the early twenty-first century. This book attempts to engage the reader in an examination of American foreign policy. It is mainly focused on the present, although I provide some historical perspective in order to add necessary context, and I indulge in some speculation about the future in order to enhance relevance. The central questions to be discussed are: How would one characterize current U.S. foreign policy compared with the past? What factors account for U.S. foreign policy behavior? What are the pros and cons of the present policy? And what foreign policy options might the United States pursue in the near term? In other words, how would you, the reader, describe U.S. foreign policy? How would you explain it? And how would you evaluate it and prescribe possible alternatives? I am particularly interested in exploring the difficult foreign policy choices—dilemmas—that confront the United States today in a post–Cold War environment that is arguably more complex, if not more dangerous, than the Cold War system that lasted for a half century after World War II.

A WORLD OF TROUBLES

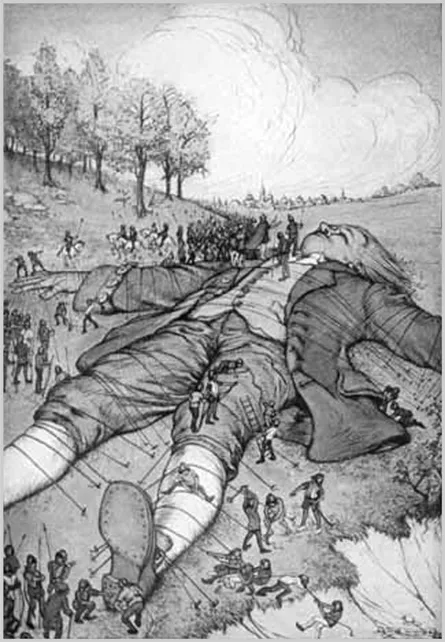

If there is a single country whose foreign policy is most worth analyzing, if only for its potential impact on the rest of the planet, the United States stands out as the number one candidate. As the above epigraph by Brooks and Wohlforth points out, the United States today, at least on paper (based on military, economic, or any other standard criteria used to measure power), gives the appearance of Gulliver in a world of Lilliputians, resembling the main character in Jonathan Swift’s famous fictional account of a man abroad who physically towers over his foreign hosts. Following the decline of its erstwhile Cold War rival—the Soviet Union—the United States would seem to have no serious challenger as a “great power.” To quote Richard Haass, the United States is “the first among unequals.”1 Haass puts it even more plainly when he says that “the United States is the 800-pound gorilla, whether it is in the room or not.”2 However, as the Niall Ferguson epigraph suggests, American strength may be illusory. Power is best understood not as a commodity whose possession alone confers influence but rather as a relationship that consists in the ability to get someone to do something they would not otherwise do.3 In the post–Cold War world, the United States, like Gulliver, reminds one of a pitiful giant, whose hands are tied by forces it seems unable to control, Iraq serving as a metaphor for American frustrations experienced all over the globe.

CARTOON 1.1 Gulliver’s Travails. CREDIT: GULLIVER’S TRAVELS, ILLUSTRATIONS BY MILO WINTER. RAND MCNALLY, 1936

One might rightly ask, where is the United States getting anybody to do its bidding? Mexico, where Washington has been unable to get cooperation to secure the border and stem the tide of illegal immigrants that had exceeded twelve million by 2007? The Middle East, where, in addition to the Iraq problem, Washington has been unable to broker peace between the Israelis and Palestinians, has been unable to thwart the threat posed by al-Qaeda and Islamic terrorism, and has failed to convince Iran to renounce its nuclear weapons ambitions? East Asia, where the United States has experienced similar struggles in trying to prevent a petty despot in North Korea from developing nuclear weapons technology, and where China continues to test American resolve in support of Taiwan’s autonomy from Beijing? Africa, where genocide in Sudan and the persistence of dictatorships in Zimbabwe and elsewhere on the continent run counter to the U.S. efforts of promoting human rights and democracy? Latin America, where a growing number of left-wing regimes, particularly in Venezuela, thumb their noses at what they see as another chapter in American imperialism? Russia, whose recent votes on the United Nations Security Council have been mostly hostile, or at best indifferent, to U.S. interests? Europe, where the French and many other North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) allies are often critical of American foreign policy and have resisted Washington’s worldview on issues ranging from reduction of agricultural trade barriers to global warming to the formation of a new International Criminal Court aimed at punishing war crimes? And, of course, at home there is the fearful prospect of possibly another attack like 9/11.

During the Bush presidency, there were headlines such as “For Bush, A World of Worry: Abundant Troubles but Few Solutions.” As the Bush presidency was nearing its end, another headline expressed anguish over “After Bush: How to Restore America’s Place in the World.”4

To be sure, the United States is not without power. It has achieved some successes since the Cold War, which ended in 1990—for example, in stopping Saddam Hussein’s aggression against Kuwait in the First Persian Gulf War in 1991 (the United States suffered fewer than 150 battlefield fatalities in forty-eight days of fighting) and in stopping Serbian president Slobodan Milosevic’s ethnic cleansing of Albanians in Kosovo in 1999 (the United States had no combat deaths despite flying some ten thousand sorties for seventy-eight days). However, one could argue that the real test of power is not so much the capacity to engage in raw coercion as the capacity to persuade others short of the actual use of armed force, either by simply threatening to use force or, better yet, offering positive incentives to cooperate, or convincing through sheer moral suasion.

Take, for instance, the case of Kosovo, where the United States was not strong enough to deter Serbia from engaging in the genocidal behavior of which Washington disapproved. As one observer noted:

When U.S. diplomat Richard Holbrooke met with Milosevic [whose country had a population 3 percent the size of the United States with a GNP only 0.2 percent that of the United States, and a defense budget $270 billion smaller] in October 1998 to negotiate the status of Kosovo, Holbrooke tried to impress the Serb leader by bringing along Air Force Lieutenant General Michael Short. . . . Milosevic greeted Short by remarking, “So you are the man who is going to bomb me.” And when Short told the Serbian president that he had “U–2s in one hand and B–52s in the other, and the choice [of which I use] is up to you,” Milosevic “just sort of nodded” . . . and chose to face war.5

Although the United States ultimately prevailed, as Milosevic was forcibly removed from power, the Balkans remained an ethnic powderkeg, and (in the view of many) the benefit of a fragile peace was achieved only at the cost of considerable harm to America’s reputation; the bombings caused thousands of civilian deaths (the reliance on air power and the resulting collateral damage attributable mainly to the U.S. fear of committing ground troops), violated the UN Charter’s proscription against aggression and noninterference in the internal affairs of other countries, and contributed to the world’s growing perception of the United States as a bully who claimed to be a champion of international law while ignoring it when it conflicted with American goals. If this was evidence of a display of power, one wondered what weakness and failure looked like.

In Kosovo, Iraq, and elsewhere in contemporary international relations, power seems not what it used to be. True, throughout history, military might has never been an ironclad guarantor of successful exercise of influence. The axioms attributed to Frederick the Great (the eighteenth-century ruler of Prussia) that “diplomacy is only as good as the number of guns backing it up” and “God is always for the biggest battalions” have always proved a bit simplistic, as quantitative military superiority has not automatically assured effective diplomacy any more than it has assured long-term victory, when diplomacy has failed and given way to the resort to war. But these nostrums seemed somewhat more reliable as predictors of events in the past than they are today in an age when the threat to use armed force is irrelevant to a growing number of issues (such as getting countries to lift their restrictions on genetically modified food imports from the United States) and when, where it is relevant, huge arsenals can now often be neutralized by “asymmetrical warfare” conducted by numerically or technologically weaker foes (for example, in Iraq).

“IT’S FOREIGN POLICY, STUPID”

Frederick the Great might have added that a state is only as good as its leadership, as the quality of its statesmanship. Charles Kupchan sees this, and not the absence of power, as the critical problem afflicting the United States:

America today arguably has greater ability to shape the future of world politics than any other power in history. The United States enjoys overwhelming military, economic, technological, and cultural dominance. America’s military has unquestioned superiority against all potential challengers. The strength of the dollar and the size of its economy give the United States decisive weight on matters of trade and finance. . . . The information revolution, born and bred in Silicon Valley and the country’s other high-tech centers, gives U.S. companies, media, and culture unprecedented reach. . . .

The opportunity that America has before it also stems from the geopolitical opening afforded by the Cold War’s end. Postwar periods are moments of extraordinary prospect, usually accompanied by searching debate and institutional innovation [for example, the creation of the Concert of Europe after the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, the League of Nations after World War I in 1919, and the United Nations after World War II in 1945], all . . . born of courageous and creative efforts to fashion a new order.

Despite the opportunities afforded by its dominance, America is squandering the moment. The United States has unparalleled potential to shape what comes next, but it has no grand strategy, no design to guide the ship of state. Rather than articulating a new vision of international order and working with partners to make that vision a reality, America has been floundering. The United States is a great power adrift, as made clear by its contradictory and incoherent behavior.6

Bill Clinton, when running for president in 1992, famously used the campaign slogan, “It’s the economy, stupid,” claiming that domestic economic issues seemed the most daunting challenges to the country at the time and that he was best equipped to handle those. These days, it would seem, “It’s foreign policy, stupid,” although it is not clear who is equipped to deal with the external challenges facing the United States.

Kupchan raises interesting questions, such as how much freedom or constraint does a country such as the United States have in its foreign policy, and how well-planned can any country’s foreign policy hope to be? These are not new questions, however. This is not the first time the United States has been compared to the literary figure Gulliver, a shipwrecked soul reduced to a muscle-bound oaf who was clumsily trying to cope in a foreign environment whose inhabitants it physically dwarfed. In the immediate post–World War II period, following the wartime devastation of many European and Asian economies, and before the Soviet Union had acquired the atomic bomb and had joined America as a “superpower,” the United States in some respects enjoyed an even greater power differential than today. As Harold Laski commented in 1947, “America bestrides the world like a colossus; neither Rome at the height of its power nor Great Britain in the period of its economic supremacy enjoyed influence so . . . pervasive. It has half the wealth of the world today in its hands, it has more than half of the world’s productive capacity, and it exports more than twice as much as it imports.”7 One could have added that “Americans possessed 70 percent of the world’s automobiles, 83 percent of its aircraft, 50 percent of its telephones, and 45 percent of its radios.”8 Yet then, too, for all the praise eventually given the Marshall Plan foreign aid program and other postwar efforts, Washington was criticized initially for erratic and misguided foreign policy behavior—the “lack of any general agreement” concerning “the basic purposes” of foreign policy—and for not taking advantage of its many strengths.9 Similarly, during the Vietnam era of the 1960s, at a time when what was thought by some to be “the greatest power in the world” was unable to defeat “a band of night-riders in black pajamas,”10 one could find books like Gulliver’s Troubles, Or the Setting of American Foreign Policy that warned of U.S. policy “in crisis” and full of “incoherence and contradictions.”11

If the United States often has been criticized in the past as a gangly giant lacking sure footing in foreign policy, there is something about the current era, as Kupchan argues, that seems to invite special scrutiny. Perhaps never before in the annals of foreign policy has there been such a disconnect between potential and performance; perhaps never before has an actor seemingly achieved so little with so much going for it.

One measure of the failure of American foreign policy in the post–Cold War era is the lack of respect enjoyed by the United States worldwide, even among it...