- 396 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book focuses on the trials and tribulations of Albania's efforts to create a democratic political order. It assesses the degree and significance of changes since the early 1990s, providing a detailed account of the transition from Communist Party rule to multiparty competition.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Albania In Transition by Elez Biberaj in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Albania in Geographical and Historical Context

Albania occupies a highly strategic position at the southern entrance to the Adriatic and it has been a tempting prize for any Great Power interested in dominating or exerting an influence in the Balkans. The country’s strategic location has greatly influenced its history and development and has been the source of many vicissitudes. A battleground between Eastern and Western influences, Albania has witnessed successive invasions and conquests by Celts, Romans, Goths, Slavs, and Turks. Yet, despite centuries of foreign occupation, the rugged remoteness of Albanian territories and the sheer willpower of Albanians to resist assimilation made the preservation of a separate Albanian identity and language possible. Although Albanians at various times have occupied a much wider territory, foreign invasions drove them into the areas in which they now live.

Physical and Human Geography

Albania is bounded to the north by Yugoslavia, to the east by Macedonia, and to the south and east by Greece. The 529-kilometer border with Yugoslavia and Macedonia runs northward from Lake Prespë to the Adriatic Sea, west of Shkodër. The border with Greece is 271 kilometers long, running southwest from Lake Prespë to the Ionian Sea. To the west and southwest, Albania is bordered by the Adriatic and Ionian Seas. Its immediate western neighbor, Italy, lies less than 100 kilometers away.

The smallest of the Balkan countries, Albania encompasses an area of 28,748 square kilometers, with a maximum length from north to south of about 340 kilometers and a maximum width of about 150 kilometers. It is predominantly a mountainous country with rugged terrain, which hindered internal communication as well as the growth of a national consciousness. The greater part of its territory, 76.6 percent, consists of mountains and hills more than 200 meters above sea level; the remainder, 23.4 percent, consists of plains and valleys. The Alps of Albania, part of the Dinaric mountain system, extend over the northern portion of the country, with elevations of close to 2,700 meters. The region has limited arable land and is sparsely populated. Forestry and animal husbandry form the main economic activities. The central mountain region, extending from the valley of the Drin river in the north to the central Devoll and the lower Osum valleys in the south, has a less rugged terrain and is more densely populated than the Alps region. It is characterized by substantial deposits of such minerals as chromium, ferronickel, and copper. Forestry, animal husbandry, mining, and to an extent, agriculture are the main economic activities in this region. South of the central mountain region is a series of mountain ranges, with elevations of up to 2,500 meters, and valleys. Although the Alps and the mountains of the central region are covered with dense forests, the mountains of the southern region are mostly bare and serve essentially as pasture for livestock. In contrast to the three mountain regions, western Albania, stretching along the Adriatic coast, consists of low-lying, fertile plains. The most densely populated region in the country, this area extends over a distance of nearly 200 kilometers into the interior of the country. This is Albania’s agricultural and industrial heartland. The 740-kilometer-long Albanian littoral on the Adriatic is well known for its splendid beaches and the beauty of the surrounding landscape.

Endowed with considerable mineral resources, Albania can be divided into two distinct geological regions. The southwestern part of the country is rich in hydrocarbons and fuels, including oil and natural gas. With its reserves of oil and gas, Albania should be in a position to meet its domestic needs. In recent decades, however, oil production has declined steadily, primarily due to the lack of modern technology for exploration and recovery. After a peak in 1974 at 2.25 million tons, oil production in 1994 was reported at less than 535,345 tons. Natural gas production has suffered a similarly drastic decline, from a peak of 940 million cubic meters in 1982 to 52,118 cubic meters in 1994.1 The northeastern region has substantial reserves of chromite, copper, lignite, iron, and nickel. Before it experienced a drastic contraction in economic activity in 1990-1992, Albania was the world’s third largest chromium producer, after the former Soviet Union and South Africa. Its chromium reserves are estimated at 37 million tons. Albania also has huge amounts of copper, with reserves amounting to some 50 million tons.2

Demographic Trends

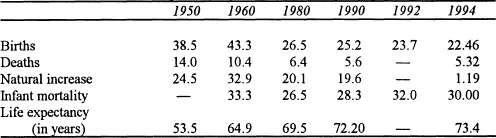

Albania has one of the highest birth rates in Europe. Between 1945 and 1990, its population increased at an annual rate four to five times higher than the average in other European countries. Since 1990, however, population growth rates have declined. In 1994, Albania registered a birth rate of 22.46 per thousand, down from 25.2 in 1990 (see Table 1.1). The highest rates of live births per thousand in 1990 were registered in the districts of Kukës (35.1), Dibër (32.7), Pukë (30.6), Mat (29.2), Librazhd (28.9) and Tropojë (28.0), and the lowest in Tiranë (21.1), Korçë (21.1), Sarandë (22.1), Permet (22.8), and Kolonjë (22.9).

TABLE 1.1 Albanian Vital Population Statistics (Per 1,000 of the population)

Sources: Vladimir Misja, Ylli Vejsiu, and Arqile Bërxholli, Popullsia e Shqipërisë [The Population of Albania] (Tiranë, 1987), pp. 22, 102, and 351; Directory of Statistics, Statistical Yearbook of Albania 1991 (Tiranë, 1991), pp. 36, 41, and 71; the Institute of Statistics, Statistika (Tiranë), no. 1 (May 1993), p. 1.

Family planning was introduced in 1992. Nevertheless, according to the Health Ministry’s Family Planning Center, only an estimated 32,000 women used contraceptives in 1993. Although Albania registered 82,177 newborns in 1990, the number in 1993 was down to 67,766. Maternal mortality declined from 49 per 100,000 live births in 1989 to 31 in 1992.3 During Communist rule, abortions were illegal. Nevertheless, unsafe abortions took place outside the health-care system and were a major cause of death among women of childbearing age. Abortions were legalized in June 1991. Since then, the number of registered abortions has increased significantly, averaging about 30,000 per year.4 The introduction of family planning and the legalization of abortion have been controversial.5 In late 1995, the parliament passed a law aimed at strictly regulating abortion.6

During the early 1990s, the population increased yearly by about 60,000, but the total population showed only a slight increase, rising from 3,182,417 in 1989 to 3,256,000 in mid-1995.7 These numbers reflect the mass exodus from Albania during the upheaval that accompanied the demise of the Communist regime. Since late 1990, close to half a million Albanians have fled the country in search of jobs and abetter life, making this one of the most massive outward migrations of Albanians since the fifteenth century. While increased emigration has served as a safety valve, high birth rates will continue to strain the country’s resources.

Albania has the youngest population in Europe: The average age in the mid-1990s was twenty-six years, and more than a third of the total population was under fifteen. By 1995, life expectancy had reached seventy-three years. But despite significant improvements in health care during recent decades, Albania has continued to have a high mortality rate (5.32 per thousand, in 1994). The infant mortality rate also has remained disturbingly high, at 30 per 1,000 live births in 1994. The highest infant mortality rates for 1990 were registered in the northeastern districts of Kukës (38.9 for every 1,000 live births), Dibër (36.6), Pukë (36.4), and Tropojë (35.0).8 These districts are also Albania’s poorest in economic terms.

Albania has one of the most ethnically homogeneous populations in the world, with Albanians accounting for 98 percent of the total population. The other two percent is made up of ethnic Greeks, Slavs, Vlachs, and Roma. According to official statistics, in 1989 there were 58,758 ethnic Greeks, concentrated mainly in the Gjirokastër and Sarandë districts. The postcommunist government has estimated the number of ethnic Greeks at between 70,000 and 90,000.9 Greek sources, however, have given contradictory statistics, depending on the state of Albanian-Greek bilateral ties. The most often heard Greek figures indicate that there are between 100,000 to 400,000 ethnic Greeks live in Albania. Albanians respond by insisting that Athens considers all Albanian citizens of the Orthodox faith ethnic Greeks. Whatever the exact number, the size of the ethnic Greek community has declined since 1991, due to a continuous outmigration to Greece.10

Until 1992, Albania was divided into twenty-six administrative districts (rrethe). In 1992, the number of trethe was increased to thirty-six. The largest and economically most important are Tiranë, Durrës, Shkodër, Elbasan, Vlorë, Korçë, and Fier. The capital, Tiranë, the country’s main industrial and cultural center, in 1992 had a population of some 260,000. Other large cities include: Durrës (about 125,000), Shkodër (85,000), Elbasan (101,000), Vlorë (85,000), and Korçë (73,000).11 Under Communism, population movement was strictly controlled and migration from the countryside into the cities was discouraged. Although the Communist policy of rapid industrialization resulted in the gradual increase of urban population, the population remained unevenly distributed between rural and urban areas: In 1992, the majority, 63.5 percent, lived in the countryside, and 36.5 percent in the cities.12 The end of Communism, however, brought significant changes in the country’s urban and regional population distribution. By mid-1997, the rural population had dropped to about 55 percent as a result of migrations, primarily from the impoverished northeastern regions, into the cities. Tiranë’s population was estimated to have increased to more than 400,000.

Albanians Outside Albania

Ironically, more Albanians live outside than inside Albania. Along almost all its borders with Yugoslavia and Macedonia are Albanian-speaking regions, which in the opinion of most Albanians, should have been incorporated within the Albanian state when the Great Powers delimited its borders in 1913.

The number of Albanians outside Albania is uncertain. Ethnic Albanians have questioned official Yugoslav censuses, insisting that the authorities deliberately underreported their number for political reasons. They boycotted the last census held by former Yugoslavia, in 1991. Belgrade estimated the number of Albanians in Kosova in 1991 at 1.6 million; but the Albanians put their number at about 2 million. While there are disagreements regarding the size of the Albanian community, there is widespread agreement that the Albanians account for over 90 percent of Kosova’s population. Ethnic Serbs constitute a majority in only four Kosova communes: Zveçan (79 percent), Subin Potok (53 percent), Leposavić (87.7 percent), and Stroc (66.3 percent).13 Some 100,000 Albanians live in Serbia proper, 80,000 of them in three southern communes on the border with Kosova: Presheva, Bujanovc, and Medvegja.

According to the 1994 census, the Albanians in Macedonia number about 442,000, or about 23 percent of the total population.14 The Albanians dispute these figures, claiming that they represent between 30 and 40 percent of the total population. They maintain that several hundred thousand Albanians were not counted in the census because the law on citizenship, approved by the Macedonian parliament in 1992, established a fifteen-year residency requirement for citizenship. Albanian residents who did not have appropriate documents or who had lived for extended periods in other parts of former Yugoslavia were not counted.

Montenegro also has a sizeable Albanian population. According to the 1991 census, there were 40,880 Albanians there, representing more than 6 percent of the total population. Albanians are concentrated in the east, in Plavë (Plav) and Guci (Gusinje), and on the coast, around Ulqin, where they represent more than 70 percent of the population of Ulqin.15

Although Albania, Kosova, and Albanian-inhabited areas of Macedonia and Montenegro have developed independently of each other since their forced partition in 1912, Albanians on both sides of the border view themselves as members of the same nation and use the same standard literary language. Demographic developments among the Albanians in Serbia, Montenegro, and Macedonia closely resemble those among their counterparts across the border. Population growth in Kosova is estimated at about thirty per thousand, making it among the highest in the world. About 67 percent of the population live in rural areas. Sixty percent of Kosova’s total population is under twenty-seven years old. Infant mortality, however, is very high. In 1994, it was reported at 33.6 per 1,000 live births.16 The Albanians in Macedonia, inhabiting compact territories in the western part of the country adjacent to Albania and Kosova, have a very high birth rate. More than half of them (52.6 percent) are under the age of nineteen. Since 1981, the Albanian population in Macedonia has witnessed an average annual increase of about 35,000, while the more numerous Macedonians have increased by about 45,000.17 With their lower birth rates, the Macedonians fear that the Albanians eventually will outnumber them.

Large Albanian communities also reside in Greece, Italy, and Turkey. Greece does not recognize the existence of an indigenous Albanian ethnic group and the number of indigenous Albanians there is not known. At the end of World War II, the Greeks expelled some 30,000 Albanians (Çams) from Çamëria in northern Greece, accusing them of having collaborated with Nazi invaders. The Çams have become a contentious issue in relations between Albanian and Greece, with Albania insisting that they be permitted to return to Greece and receive compensation for their confiscated properties. Greece has rejected Albania’s demands. Since 1991, some 300,000 Albanians have fled to Greece, most of them illegally. The future of these Albanians remains uncertain, as Greece has on numerous occasions sent thousands of them back to Albania.

It has been estimated that some 150,000 Albanians migrated to Italy during the early 1990s. In addition to recent arrivals, Italy has a large Albanian community in Calabria and Sicily—descendants of immigrants who settled there in the fifteenth century after the Turkish occupation of Albania. The number of Albanians in Turkey is estimate...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword, Robin Alison Remington

- Introduction

- 1 Albania in Geographical and Historical Context

- 2 The Demise of Communism

- 3 The Transition Begins: Communists Cling to Power

- 4 The Road to Democratic Victory

- 5 The Democratic Party in Power (1992-1996)

- 6 Economic and Social Transformation (1992-1996)

- 7 Foreign Policy and the National Question

- 8 The Party System and the 1996 Elections

- 9 Albania in Turmoil

- Conclusion

- Selected Bibliography

- Index