- 252 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First Published in 2018. This book examines the land and people of Israel and the division between Jews of Oriental and Ashkenazi backgrounds as well as the division between Jewish and Arab citizens, offering a thoughtful discussion of the continuing Arab-Israeli conflict.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Israel by Bernard Reich,Gershon R. Kieval in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Middle Eastern Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Land and Its People

The Land of Israel

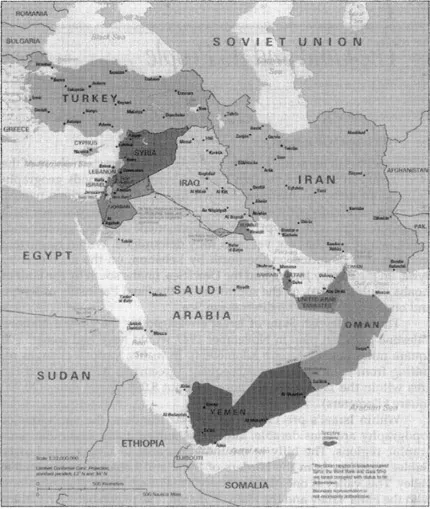

Israel lies at the southwestern tip of Asia, on the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea. The modern State of Israel corresponds geographically to an area that has been known historically by various names, including—most recently—Palestine. It is a small country whose land borders (except with Egypt) are not permanent and recognized and, hence, whose size has not yet been fully determined. Within its current frontiers it is bounded on the north by Lebanon, on the northeast by Syria, on the east by Jordan and the Dead Sea, on the south by the Gulf of Aqaba (Gulf of Eilat), on the southwest by the Sinai Peninsula of Egypt, and on the west by the Mediterranean Sea.

The new Jewish State of Israel envisaged by the United Nations Palestine partition plan in November 1947 would have had some 5,600 square miles (14,500 square kilometers). In reality, various changes resulting from wars and from subsequent agreements have enlarged the area within the 1949 armistice lines to about 8,000 square miles (20,700 square kilometers).

Within Israel’s pre-1967 Six Day War frontiers, the variations of topography are considerable, and it has substantially dissimilar geographic regions. The hilly to mountainous area of Upper and Lower Galilee stretches from the borders of Syria and Lebanon to the Jezreel Valley. This valley is one of the country’s major agricultural areas, along with the Hula Valley and the Plain of Sharon. The region between Galilee and the central sector, from the Jordan depression to the Mediterranean, includes the fertile upper Jordan Valley (a prosperous wheat and vegetable area), the Bet She’an Valley, and the Jezreel Valley. The western coastal plain extends roughly from Mount Carmel south past Tel Aviv to the flat plain in the region beyond Rehovot, Ramie, and Lod. The coastal plain is devoted to the cultivation of citrus and to other types of agriculture,

Source: U.S. Government

such as vineyards. The location of a considerable amount of small industry around Tel Aviv and the other sizable towns and cities of the plain, however, has converted some of the cultivable land to urban uses. The hills of the Samaria area contain a number of fertile valleys, whereas the Hills of Judea that stretch south from Jerusalem are mainly barren. The Negev desert stretches south from Beersheba and the Dead Sea to Eilat on the Gulf of Aqaba; geographically it is an extension of the Sinai desert. It is almost entirely arid and accounts for more than half of the country’s land area. About one-third of the country is cultivable.

Israel is situated between subtropical wet and subtropical arid zones of climate. As a result rainfall is light in the south and heavier in the north. The country is generally sunny because of its subtropical location and extensive desert areas. Rainfall usually takes place between November and May—with about three-quarters in December, January, and February.

Israel has a number of permanent rivers, but none is substantial by international standards. The Jordan, the largest river, originates in the Dan, the Banyas, and the Hasbani rivers and flows from the north to its terminus in the Dead Sea—the lowest point on earth at more than 1,300 feet (about 400 meters) below sea level. Israel’s water-based resources include Lake Tiberias (also known as the Sea of Galilee or Lake Kinneret), a source of fresh water and fish. Israel’s water needs and the scarcity of resources lead it to utilize most of its water potential to the fullest, primarily for agriculture. Water resources have been tapped at substantial cost and effort; water is derived primarily from the upper Jordan, Lake Tiberias, and the Yarkon River and from groundwater on the coastal plain. The National Water Carrier, put into operation in 1964, brings water from Lake Tiberias through a series of pipes, aqueducts, open canals, reservoirs, tunnels, dams, and pumping stations to various parts of the country, including the northern Negev.

Israel is relatively poor in natural resources, although it has copper and phosphates, glass sand, and building stone. The Dead Sea, shared by Jordan and Israel, is a major source of minerals (including potash, bromine, and magnesium). Much of the mineral resource is exported and is an important source of foreign exchange. Energy resources (coal, gas, and oil) provide only a small portion of the country’s needs, making oil imports a heavy burden for the economy.

The majority of Israel’s population is located in the narrow coastal plain along the Mediterranean. Haifa, the country’s third-largest city and a major port, is the site of much heavy industry. Tel Aviv, the second-largest city, is the center of a large metropolitan area and serves as the economic, business, and banking center; the headquarters of the trade unions and the political parties; and the location of the Defense Ministry and General Staff. It is also a center of newspaper publishing, art, theater, and music. The largest city, Jerusalem, is the capital (although virtually all foreign embassies remain in Tel Aviv) and the country’s spiritual center.

Agriculture and agricultural settlements have played an important role in the Zionist efforts to create a Jewish state and in Israel’s efforts to develop a flourishing society. Jewish settlement in Palestine from the beginning of the Zionist movement until the end of the British mandate stressed agriculture as a means of reclaiming land and as a way of demonstrating the pioneering spirit central to Zionism. This focus has remained important, and the governments of Israel have encouraged immigrants (and others) to work the land and have considered agricultural training in border areas (in the Noar Halutzi Lohaim [NAHAL] program) the equivalent of military service.

In the early days of the new state, the development of agriculture was a major concern in order to provide food for a rapidly growing population and to conserve scarce hard currency through self-sufficiency in food. In more recent years, after meeting its own needs, Israel has become more oriented toward agricultural exports. Citrus has been the most important crop and substantial exports, primarily to Western Europe, have helped to earn important foreign exchange. Over time, the focus on agriculture has diminished as advances in agricultural techniques have made it possible to generate greater yields with fewer participants, and Israelis have become more oriented toward industry and urban life.

Israel’s population is overwhelmingly urban with heavy concentrations in the three largest cities. Despite this, Israel is associated in the minds of many with agriculture and with its unique experiment—the legendary kibbutz, one of the unusual forms of habitation and economic organization developed for Israel’s population to realize the goals of the state. The others are the moshav and the development town.

The kibbutz (a word meaning collective settlement that comes from the Hebrew for group) is a socialist experiment—a voluntary grouping of individuals who hold property in common and have their needs satisfied by the commune. Every kibbutz member participates in the work. All the needs of the members—from education to recreation, medical care to vacations—are provided by the kibbutz. The earliest kibbutzim (plural of kibbutz) were founded by pioneer immigrants from eastern Europe who sought to join socialism and Zionism and thus build a new kind of society They have been maintained by a second and third generation as well as by new members. Initially, the kibbutzim focused on the ideal of working the land and became known for their crops, poultry, orchards, and dairy farming. As modern techniques, especially automation, were introduced and as land and water became less available, many of the kibbutzim shifted their activities or branched out into new areas, such as industry and tourism, to supplement the agricultural pursuits. Kibbutz factories now manufacture electronic products, furniture, plastics, household appliances, farm machinery, and irrigation-system components.

The popular and romantic image of the kibbutz conveys the impression of a movement of major proportions, but actually it is relatively small. The first kibbutz—Degania—was founded in 1909; today there are some 265 kibbutzim with a membership of some 125,000, or about 2.5 percent of Israel’s population. Despite their small proportion of the country’s population, the kibbutzim have had substantial influence in Israel’s political and official life. Kibbutz members are found in the Knesset (parliament) and the cabinet and in the senior ranks of the Histadrut (the General Federation of Labor) and other agencies and organs of official and semiofficial Israel. Kibbutz members have been disproportionately overrepresented in the officer ranks and elite units (such as the air force, paratroop, and commando units) of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF or ZAHAL—the Hebrew acronym for Tzvah Hagana Leyisrael).

The kibbutzim are divided, with some exceptions, into several federations reflecting various political and ideological perspectives. Ihud Hakevutzot Vehakibbutzim was affiliated with MAPAI elements of the Israel Labor party. Hakibbutz Haartzi is affiliated with MAPAM (the United Workers party), which advocates a stricter Marxist ideology; Hakibbutz Hameuchad was identified with the Ahdut Haavoda wing of the Labor party. Hakibbutz Hadati combines communal life and a socialist ideology with Orthodox Judaism and is affiliated with the National Religious Party, although some kibbutzim identify with Poalei Agudat Yisrael. The Ihud and Hameuchad federations have merged into what is known as the United Kibbutz Movement (Hatenuah Hakibbutzit Hameuhedet).

A moshav is a village composed of a number of families—the average is about sixty—each of which maintains its own household, farms its own land, and earns its income from what it produces. The moshav leases its land from the Israel Lands Authority or the Jewish National Fund (Keren Kayemet Leyisrael) and, in turn, distributes land to each of its members. Each family belongs to the cooperative that owns the heavy machinery and deals collectively with marketing and supplies and provides services such as education and medical care. Some now engage in industry under similar conditions. The first moshav, Nahalal, was founded in 1921 in the Jezreel Valley. Private homes, rather than communal living, are the rule, as are private plots of land and individual budgets. Moshavim (plural of moshav) have become more numerous than kibbutzim, and by 1992 they numbered about 450, with more than 160,000 participants. Many of the postindependence immigrants to Israel were attracted to the concept of cooperative activity based on the family unit rather than the kibbutz’s socialist communal-living approach.

Peculiar to Israel is the third type of settlement, the development towns. They were established in the 1950s and became focal points for new immigrants, predominantly those from Asia and Africa who arrived with few personal resources. Towns such as Kiryat Shmona, Maalot, Karmiel, Migdal Haemek, Bet Shemesh, Ashdod, Netivot, Arad, Dimona, and Mitzpe Ramon were created as part of a conscious government policy to serve as urban centers for new immigrants, to spread Israel’s population throughout the country, and to provide a nucleus for the development of specific areas of the country. They have become integrated into Israeli life, and some have made significant contributions to the country.

Israel’s Jewish Population

Israel has a small population. On independence in May 1948, there were approximately 806,000—650,000 Jews (about 81 percent) and 156.000 non-Jews (mostly Arabs). By May 1992 Israel’s population was 5,090,000—some 4,175,000 Jews (about 82 percent), approximately 700.000 Muslims, around 130,000 Christians, and 85,000 Druze. The increase in the non-Jewish population was a result of high birthrates; the increase in the Jewish component was due primarily to immigration. An estimated 62 percent of Israel’s Jewish population were sabras (native bom). Table 1.1 presents data on Israel’s population.

Israel is by self-identification a Jewish state. The connection of the Jewish people with the land of Israel has continued throughout history. Jewish presence in the area was maintained even after the creation of the Diaspora (the dispersion of the Jews outside of Palestine after the Babylonian captivity and the Jews or Jewish communities outside of Palestine or Israel) although the numbers and the status of Jews declined as that of other populations increased. The Jewish community in Palestine prior to the waves of Zionist immigration was concentrated in a number of important cities, notably Jerusalem, and focused on religious interests and activities.

The Jewish population is composed of immigrants from numerous countries and reflects a variety of ethnic and linguistic groups, religious preferences, and cultural, historical, and political backgrounds. The dispersion of the Jews had led to the creation of numerous communities located throughout the Diaspora, each of which was influenced by local customs that it integrated into its rituals and the practice of its faith. Each community developed diverse institutions, customs, languages, physical traits, and traditions. These were transferred to Israel with the communities.

The two main groupings are the Ashkenazi Jews and the Sephardim.

Table 1.1 Population of Israel, by Religion, Origin, and Birthplace, 1948–1990 (in thousands)

Ashkenazi Jews, primarily from eastern and central Europe, were the main components of the first waves of Zionist immigration to Palestine, where they encountered a small Jewish community that was primarily Sephardi in nature. The Ashkenazim had fled from the Jewish ghettos of Europe (including Russia) and sought to build a new society, primarily secular and socialist in nature. The more religious brought with them their East European customs, fashions, and language (Yiddish, a German-based language written in Hebrew letters, was their language of everyday communication). Today the Ashkenazi community includes sizable groups from Western Europe, North America, and the British Commonwealth. The more religiously orthodox include in their number very small, but active and vocal, sects (such as the violently anti-Zionist Neturei Karta of Jerusalem and its colleagues in the United States) that refuse to accept the legitimacy of the state and of the everyday use of Hebrew (the language of the Old Testament and thus for them holy).

Israel’s non-Ashkenazi Jews are a majority of the country’s population. These people, of Afro-Asian origin, are referred to as Edot Hamizrach (eastern, or Oriental, communities), Sephardim, or Orientals. The term Sephardim is often used to refer to all Jews whose origin is in Muslim lands, although it properly refers to the Jews of Spain and the communities they established in areas to which they migrated after their expulsion from the Iberian peninsula during the Inquisition. Although technically incorrect, Sephardim has increasingly come to include both those whose origins were in the Iberian peninsula and those who had been located throughout the Arab world and the more broadly defined Middle East (including Turkey, Greece, Iran, and Afghanistan) for centuries following the exile from the historical Jewish state. The Iberian Jews generally spoke Ladino, a Judeo-Spanish language originally written in medieval Hebrew letters and later in Latin letters (much as the Ashkenazi Jews spoke Yiddish), whereas those of the Middle Eastern communities did not. Most of the Oriental immigration came after Israel’s independence from the eastern Arab states (such as Iraq) and from Iran, where the Jews had resided for more than two thousand years and often had substantial centers of learning. The community is diverse and pluralistic, although a collective “Oriental” identity appears to be emerging.

Immigration

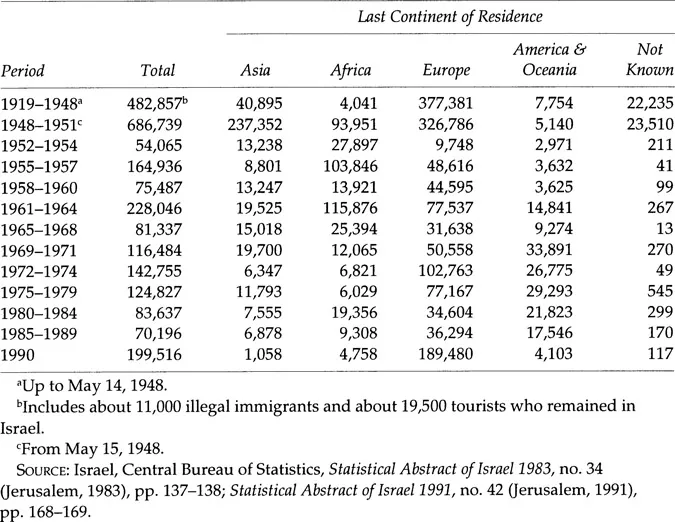

Israel’s role as the world’s only Jewish state has led to its national commitment to a policy of virtually unrestricted immigration—an outward expression of a bond of faith between Israel and world Jewry that results from Israel’s view of its mission as the emissary of the exiled and scattered Jewish people (see Table 1.2). It also has given rise to Israel’s concern about the well-being of Jews everywhere. This approach serves the needs of world Jewry by removing Jews from areas of distress and serves the needs of Israel by providing the people necessary for its security and development.

Table 1.2 Immigration to Israel, 1919–1990

In Jewish tradition, immigration to Israel is referred to as aliyah (“going up”), resulting from a deep-rooted view that “in the end of days” Jews would return to Zion—to the Holy Land. Zionism made this ancient concept a contempo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Tables and Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 The Land and Its People

- 2 History

- 3 The Economy

- 4 Politics

- 5 The Quest for Peace and Security

- 6 Israel and the United States

- Chronology of Major Events

- List of Acronyms

- Suggested Readings

- About the Book and Authors

- Index