- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

InCouple Burnout, Ayala Pines offers a unique model to combat relationship burnout by describing the phenomenon of couples burnout; its causes, danger signs and symptoms; and the most effective strategies therapists can use. Distinguishing burnout from problems caused by clinical depression or other pathologies, Pines combines three major clinical perspectives that are used by couple therapists--psychodynamic, systems and behavioral--with additional approaches that focus attention on the social- psychological perspective and existential perspective to couples' problems.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Couple Burnout by Ayala Pines in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Couple Burnout:

Definition, Causes, and Symptoms

Definition, Causes, and Symptoms

How we loved in the fashion of all lovers, and strove not to let the little things of existence destroy us. How they did, and how we forgot. Just like everyone else.

—Han Suyin, A Many Splendoured Thing

“Love at first sight.” “Made for each other.” “Happily ever after.” For most people growing up in a western culture, the expectations for love and marriage are extremely high. These expectations set the stage for burnout. Even if they should know better, when they fall in love, most people hope that their love will last forever. This hope has the power to blot out awareness of obvious faults, reduce common sense, and obliterate foresight. Burnout occurs when, maintaining these idealistic notions about love, people run into the stark reality of everyday living. It is the psychological price many idealistic people pay for having expected too much from their relationships, for having poured in more than they have gotten back—or believing they have done so. Burnout is caused by too great a discrepancy between expectations and reality. With the accumulation of disappointments, with the stress of day-to-day living, comes a gradual erosion of spirit and eventually burnout.

Dona is a tall, striking woman and a successful architect in her early forties. After fourteen stormy years of marriage, Dona is burned out:

I feel hollow in this relationship. There is nothing between us: no bond, no communication, no sharing, no contact, no feelings, nothing. We have no plans together, no interests together. The tensions are making me tired and sad. There is no hope for us. There is nothing that he does that enhances my life in any way, emotionally, intellectually, physically. I don’t feel like a couple; I feel emotionally deprived. I feel resentful and irritated. I have to close myself off emotionally to stop feeling that way. I can’t give myself sexually or emotionally any more. I don’t believe life has anything to give me. I would do anything to be free of him. I have no feelings for him except irritation and sometimes pity. When I come home and he’s there I get all uptight. I wouldn’t stay with him for anything.

Dona’s husband, Andrew, a dark, good-looking man in his mid-forties, is an accountant. Describing life in a burned-out marriage he says:

It’s awful. I mean, it really is almost like living with a stranger. That’s how bad it gets. Once there’s no more interaction it’s just poof, it’s gone. I’m really living a life of quiet desperation.

Andrew and Dona’s feelings of emotional depletion, their hopelessness about their future together and helplessness to make things better, are the hallmarks of burnout, a painful denouement for many marriages. While marital problems are as old as the institution of marriage, burnout is a modern phenomenon. It has to do with the importance of romantic love to our generation, and the fact that love has become a highly valued foundation for marriage and most other couple relationships.

There are few adults growing up in this culture who do not know what “romantic love” is and who have not experienced it at one time or another in their lives. Scholars, such as Elaine Walster, who have studied romantic love define it as “a state of intense absorption in another,” and of “intense physiological arousal.” At times it involves only “longing for complete fulfillment.” For the lucky it involves the “ecstasy in finally attaining the partner’s love” (Walster and Walster 1978, 9).1

While romantic love has reigned supreme among other forms of love since time immemorial, only in recent years has it been promoted as the basis for mate selection. There is a universally shared desire to believe that the emotional bond of love is enough to sustain a long-term couple relationship. The voice of reason, which would be welcomed in any other human endeavor, is scorned when applied to mate selection. Consider, for example, a scathing description of today’s young urban professionals that appeared in a New York Times article. The author of the article dubbed the Yuppies “unromantics.” The reason: they are considering each other’s assets (country house, income potential, schooling, family) before deciding that they could make suitable marriage partners. The Yuppie approach to marriage fits the description of a famous sociologist, Erving Goffman:

A proposal of marriage in our society tends to be a way in which a man sums up his social attributes and suggests to a woman that hers are not so much better as to preclude a merger or partnership. (Goffman 1952)

To a romantic society such as ours, this kind of a steely-eyed materialism about marriage seems cold and cynical, if not entirely inaccurate. There is a shared resistance to viewing an intimate relationship as a business proposition. As a matter of fact, very few businesspeople get into a lifelong partnership with the scant information most couples have about each other. But love and marriage are viewed as affairs of the heart, and love is seen as an experience that defies reason and is meant to defy reason.

Love is seen as an act of freedom and self-determination. Romantic love has an appeal on several scores. It carries individualism to its furthest extreme. The beloved is unique and irreplaceable. In a country that considers the pursuit of happiness a birthright, it is a pure expression of this pursuit, pulling with it intimacy, family, and hopes for the future. It is even an expression of equality—differences in background do not matter to lovers. Since they are glorified in each other’s eyes, there is a sort of star-crossed equality between them.

All this is part of the ideology of romantic love. In fact, the ideology does not always match the way people actually select their mates. In reality, class, ethnic, and racial differences do matter, but there is a belief on the part of lovers (a belief shared and reinforced by society at large) that love will overcome these differences. There is a desire to believe that love can conquer all.

While everyone is exposed to information about the failure of romantic love, and some people have a firsthand experience with its fragility as the foundation of couple relationships, most people still want to continue believing in it—probably because they see no immediate or better alternative. The high divorce rates do not deter; most divorced people cannot wait to remarry and give love another chance. In fact, more people are marrying and cohabiting today than ever before in history.2 As Ingrid Bengis concluded, “The only permanent thing about love is the persistence with which we seek it” (Bengis 1972).

Love. Why are so many people today obsessed with love? The answer, I will argue, has to do with people’s need to give meaning to their lives. Romantic love is an interpersonal experience in which we make a connection with something larger than ourselves. For people who are not religious and who do not have another ideology they strongly believe in, love can be the only such enlarging experience. As Otto Rank so aptly noted, people are looking for romantic love to serve the function that religion served for their predecessors—giving life a sense of meaning and purpose (Rank 1945).

The ultimate existential concerns about the meaning of life are universal. They include, according to Irving Yalom, the terror of our inevitable death, the dread of groundlessness in the vast universe, the total isolation with which we enter life and with which we depart from it, and the meaninglessness of our own self-created mortal life (Yalom 1980).

The tremendous sense of isolation and fright attached to these concerns result from the unique duality of human beings, which Kierkegaard described 150 years ago as a “synthesis of the soulish and the bodily” (Kierkegaard 1957, 39)—the paradox of the spiritual self that can transcend life imprisoned in a mortal body that cannot escape death. From time immemorial people have attempted to deal with their feelings of existential isolation and fright by giving meaning to their lives. This can account in part for the importance of romantic love to Americans. Ever since its founding by people escaping religious persecution, America has struggled to remain secular. Since a secular society does not provide ready answers to the existential dilemma, “love,” as Erich Fromm put it, becomes “the answer to the problem of human existence” (Fromm 1956, 7).

In his Pulitzer Prize-winning The Denial of Death, Ernest Becker expands on this idea. Becker discusses the universal need to feel “heroic,” to know that one’s life matters in the larger “cosmic” scheme of things, the need to merge with something higher than oneself and totally absorbing. For modern people who reject the religious solution to the existential dilemma, one of the first alternatives has been “the romantic solution.” The “urge to cosmic heroism” is fixed on the lover, who becomes the divine ideal within which life can be fulfilled, the one person in whom all spiritual needs become focused (Becker 1973, 160).

But even people who believe in romantic love may find it difficult to admit that through it they are seeking a solution to the existential dilemma. First, this admission implies that they need another human being to make their lives matter—which can be construed as weakness of character. Second, to admit that romantic love is the vehicle for finding ultimate meaning in life is to agree that the quest for love is a religious quest. This is probably unacceptable to most people, since the substitution of romantic love for God would seem positively sacrilegious to the faithful, and unseemly to the rest.

Nevertheless, it seems to be exactly that for people who do not feel a personal connection to God and who seek a connection with something larger than themselves in romantic love. Love promises to fill the void in their lives, to eliminate their loneliness, to justify their existence, to provide security and everlasting happiness. The promise of love is attached to a specific image of a person or a relationship. When people meet a person who fits their romantic image, they fall in love. They then expect their relationship with that person to make all the promises of love come true. When the person or the relationship fails them, they burn out.

Western culture would have people believe, then, that love can answer the question of human existence, provide the best basis for marriage, and celebrate democracy, equality, freedom of choice, and the pursuit of happiness. These expectations are transmitted via popular songs, books, television, and the movies, which preach that love is the most important thing in life. Love, we are told, is what “makes the world go ‘round.” We are also told that true love lasts forever. A couple can live “happily ever after,” “till death do us part.”

People’s ideals determine expectations and the understanding they bring to bear on relationships. Those who uncritically internalize the ideals expect a relationship to solve their problems and give meaning to their life. When these expectations are not met, they are not only disappointed in their mate, but their world has no meaning.

In fact, some romantic expectations can be achieved in a couple relationship, but other expectations are totally unrealistic. People who want to live “happily ever after,” who expect the simple act of marriage to give focus and meaning to their lives and to answer all of life’s basic questions, are very likely to be disappointed. Hanging on to those notions almost guarantees burnout. Yet we are actually socialized to believe in them.

Culturally shared expectations are often expressed in truisms and proverbs. In one of my studies of marriage burnout I asked a hundred married couples to what extent they believed in ten romantic truisms such as “love at first sight” and “a match made in heaven.” (The ten are presented in the box on page 7.) I discovered that belief in such romantic truisms was correlated with marriage burnout.3 This can mean that the level of burnout (which reflects people’s experiences) influences their belief in certain truisms. Alternatively, it can mean that the belief in the truisms (by creating unrealistic expectations) influences their level of burnout.

Because we have, as a society, continually raised our expectations as to what constitutes a romantic success story, today people are more ready than ever to abandon a relationship if it fails to fulfill their expectations. The high divorce rates (the United States has the highest in the world) are one testimony to that.4 There is no longer a requirement to prove moral incertitude or “breach of contract” to end a marriage. Incompatibility—the failure of love to meet our expectations—is often grounds enough.

The expectations we have today of love are not built into human nature. As Nathaniel Branden noted in The Psychology of Romantic Love, throughout most of human history this notion of love being required for marriage was unknown:

Young people growing up in twentieth century North America take for granted certain assumptions … that are by no means shared by every other culture. These include that the two people who will share their lives will choose each other, freely and voluntarily, and that no one, neither family nor friends, church or state, can or should make that choice for them; that they will choose on the basis of love, rather than on the basis of social, family, or financial considerations; that it very much matters which human being they choose and, in this connection, that the differences between one human being and another are immensely important; that they can hope and expect to derive happiness from the relationship with the person of their choice and that the pursuit of such happiness is entirely normal, indeed is a human birthright; and that the person they choose to share their life with and the person they hope and expect to find sexual fulfillment with are one and the same. Throughout most of human history, all of these views would have been regarded as extraordinary, even incredible. (Branden 1983, 56)

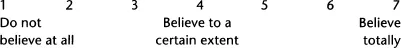

To what extent do you believe the following ten truisms, using the scale:

__Love at first sight

__A match made in heaven

__Living happily ever after

__Marriage kills love

__True love is possible only after the infatuation is over

__Love, like a good wine, can get better with time

__One should not marry for love

__People who wait for the perfect mate remain single

__A matchmaker is the best way to ensure a happy marriage

__True love is forever

Couples are asked to respond to the ten truisms, guess each other’s answers, and then compare notes.

Denis de Rougemont made similar observations about the unparalleled importance given to love in modern times:

No other civilization, in the 7,000 years that one civilization has been succeeding another, has bestowed on love known as ROMANCE anything like the same amount of daily publicity.… No other civilization has embarked with anything like the same ingenious assurance upon the perilous enterprise of making marriage coincide with love thus understood, and of making the first depend on the second. (de Rougemont 1940, 291–92)

Ironically, the celebration of love, the “daily publicity” bestowed on it, and the importance and glory attributed to it have produced an apparent scarcity rather than an abundance. Never before in history have so many people been disappointed in the promise of romantic love. Could the importance attributed to love make people more susceptible to burnout, or is this insidious process of love’s erosion indigenous to all long-term intimate relationships? My interest in such questions was the original impetus for studying couple burnout. My goal was to understand burnout, its causes and consequences, and how best to cope with it.

What Is Couple Burnout?

Burnout is a painful state that afflicts people who expect romantic love to give meaning to their lives. It occurs when they realize that despite all their efforts, their relationship does not and will not do that. Marriages can be disappointing and unhappy without being burned out. When a mate is sloppy or inconsiderate, one can decide to live and let live, but when one looks for the relationship to give meaning to one’s life, such annoyances can be unbearable.

Couple burnout is caused by a combination of unrealistic expectations and the vicissitudes of life. It is not caused—as most clinical approaches to couple therapy believe—by a pathology in one mate, in both mates, or in the relationship.

The burnout of love is a gradual process. Its onset is rarely sudden. Instead, there is a slow fading of intimacy and love accompanied by a general malaise. In its extreme form, burnout marks the breaking point of a relationship. The burned-out person is saying in one way or another: “This is it! I’ve had it with this relati...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. Couple Burnout: Definition, Causes, and Symptoms

- 2. The Couple Burnout Model: Falling In and Out of Love

- 3. Three Clinical Approaches to Couple Therapy and an Alternative

- 4. Couple Burnout and Career Burnout

- 5. Gender Differences in Couple Burnout

- 6. Burnout in Sex: The Slow and Steady Fire

- 7. Is Couple Burnout Inevitable?

- 8. High and Low Burnout Couples

- 9. Couple Burnout Workshops

- Appendix 1. The Couple Burnout Measure

- Appendix 2. Research on Couple Burnout

- Notes

- References

- About the Author