eBook - ePub

The Motherhood Constellation

A Unified View of Parent-Infant Psychotherapy

- 238 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book explores the nature of parent-infant psychotherapies, therapies that are a major segment of the rapidly growing, sprawling field of infant mental health. It examines the different elements that make up the parent-infant clinical system.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Motherhood Constellation by Daniel N. Stern in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The Clinical System in Parent-Infant Psychotherapy

CHAPTER 1

An Overview of the Clinical Situation

THE MAIN CHARACTERS in the clinical situation in parent-infant psychotherapy are one infant and one or two parents. If only one parent participates, it is invariably the primary caregiving parent—usually, but not necessarily, the mother. Thus, the "patient" is generally the mother-infant dyad or the mother-father-infant triad. And there is the therapist. In the same vein, for the sake of clarity, I will generally use the masculine pronouns in referring to the infant. This device is not intended to suggest that problems are more common with male infants but simply to avoid confusion and clumsy expressions in referring to mother and baby.

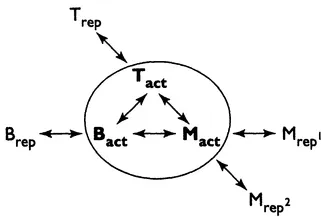

This clinical situation consists of many different elements, its working parts. To visualize the elements of this system, I will use a model that is an elaboration of a schematic presented earlier (Stern-Bruschweiler & Stern, 1989). The relevant elements will be assembled by progressively adding them to the model. Separate chapters will later be devoted to detailed descriptions of the individual elements. Here I want to give an overview.

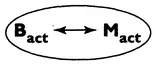

I will start with the bare minimum. At the very center of the model is the interaction between the infant and the mother. (Less often the triad is at the center. Whether it is the dyad or the triad that belongs at the center will be taken up later in this chapter.) This mother-infant interaction consists of the overt behaviors performed by each in response to and in concert with the other. The interaction is visible and audible to a third party, such as the therapist, as well as to the participant-observers.

For the purposes of schematization, let B stand for the baby and M for the mother, and the subscript act stand for their actions—that is, their overt behavior.

The observable interaction can be modeled as:

FIGURE 1.1

The basic elements for a purely behaviorist approach are now in place. A behavioral treatment based solely on what the two partners do could be implemented with these elements.

So far, however, we have only an interaction and not a relationship. A relationship is, among other things, the remembered history of previous interactions (Hinde, 1979). It is also determined by how an interaction is perceived and interpreted through the many lenses particular to the participant of the interaction. There are the lenses of fantasies, hopes, fears, family traditions and myths, important personal experiences, current pressures, and many other factors. For the purposes of the model, I will summarize this amalgam of remembered history and personal interpretation as the representation of the interaction. Thus we can add to the model the mother's representation (M rep), consisting of how she subjectively experiences and interprets the objectively available events of the interaction, including her own behavior as well as the baby's.

This added element can be modeled as follows. (Hereafter, all phenomena that are externally observable events will be in bold block letters inside the ovals, and all intrapsychic, unobservable phenomena will be in lighter type outside the ovals.) With this addition, the basic elements for a cognitive therapeutic approach or a limited psychodynamically inspired approach are now in place.

FIGURE 1.2

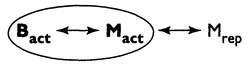

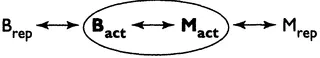

But the mother is not alone in forming a representation of what is happening during the interaction. As we shall see in chapters 5 and 6, the baby is avidly involved in constructing a representation of this interaction from the memory of its past occurrences. He too is building an interpretative and guiding representational world to deal with the current interaction. We must add an infant representation, the counterpart of the mother's representation. We thus add Brep to the model:

FIGURE 1.3

The therapist is the final member of the minimal cast of characters of this clinical situation. The therapist, like the others, not only has objective interactions with the primary caregiver and infant, but also has a representational world in which such interactions take on part of their meaning and in which the therapeutic intervention takes on its specific form. So we must add the therapist (T) to the model as follows:

FIGURE 1.4

Note that I have added a Mrep2, which is different from the Mrep1 discussed above. When the mother is in the therapeutic process, that is, actively in the presence of the therapist, she may see her infant, and herself-as-mother, and what is happening between them in a different light than when she is alone. Mrep2 is the view she acquires while in the therapeutic relationship. This parallel view can play an important therapeutic role as will be discussed below. In addition, the Mrep2 will contain the mother's views of the therapist, and the Trep will contain the therapist's views of the mother.

Now all the elements are in place for a psychoanalytically inspired approach via the mother and infant, including the provision of a role for transference and countertransference. It is now also possible for the mother's fantasy life to be seen to influence the infant's fantasies, and vice versa.

For the present, I will say no more about the therapist and temporarily leave that role out of the schematization for the sake of visual clarity. Just assume that the therapist is there as schematized. (A discussion of the therapist as a separate element follows in chapter 7.) Instead, I will now expand, schematically, the clinical situation beyond these minimal characters.

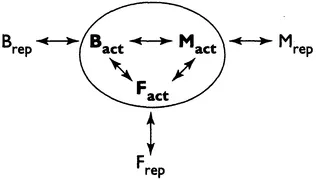

Some therapists consider the mother-father-infant triad as the "central patient." Others reserve this place for the mother-infant dyad, with the father playing a supporting and framing role. And yet others leave this question open, to be decided on a case-by-case basis. In any event, the father or his counterpart must be brought into our model. In actual practice the father's presence is variable unless it is made a condition for a session. Assuming he is there, he interacts with the mother and the infant (and the therapist), and he too evolves representations of his relationship with these others. So we can expand the model as follows:

FIGURE 1.5

We now have present all the basic elements for a family-systemic approach, with or without an emphasis on individual psychodynamic past history—that is, the representations.

Often, especially in nontraditional, nonnuclear families, the complex of characters playing relatively important caregiving roles may be expanded and variable. Accordingly, the system can be opened up to include other crucial caregivers whose biological relation to the infant is not a criterion. The elements for a larger general system approach are now in place.

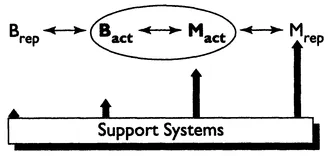

Finally, there are the levels of secondary and tertiary caregivers, support systems, social networks, and other factors at large, which are also always present, always acting, and always available as routes of therapeutic intervention. For the moment, I will collapse all these into the term support system, without recognizing the discrete potential influence of each of these factors, which include preschool nurseries, other parent-infant groupings, the medical care system, home visits, family networks, financial realities, and many others.

Support systems, in the above sense, can act as a continuous maintaining force or as an episodic influence on almost any (or several) elements of the basic model. The relationship of the support system to the basic model can be schematized as follows:

FIGURE 1.6

This schematic tries to capture the fact that the support system will have its greatest direct effects on the mother's representations (largely those of herself-as-mother and herself-as-person) and perhaps an equally great effect on what the mother does, behaviorally, with the baby. The direct effect of the support system on the baby's overt behavior will be much smaller and on the baby's representations almost negligible, because the efforts of the support system are mainly directed at the mother's maternal functioning.

Four basic points are highlighted by this model. First, almost all the elements are always present and acting. Second, all the elements are interdependent. Third, all the elements are in a dynamic, mutually influencing relationship. Finally, and most relevant, a successful therapeutic action that changes any one element will end up changing all the separate elements. For instance, if one can change how a mother subjectively experiences herself as a mother—that is, her representation of herself with her infant (Mrep)—she will end up behaving differently with her infant in at least some of their interactions (that is, Mact will also change). The infant then will have to alter his behavior (Bact) to adjust to the new interactive reality. Since the infant's representation of the interaction (Brep) depends on what happens during repeated interactions, he will be forced to take his changed behavior and that of his mother into account by readjusting his representation of current and future interactions; that is, his representation (Brep) will have changed. And so the chain reaction occurs no matter where the first change was made. It could have occurred with the mother's interactive behavior (Mact) rather than with her representations (Mrep) with the same ultimate spread of changes throughout the model.

From this point of view, the different therapeutic approaches can be viewed as utilizing different ports of entry into a single dynamically interdependent system. To the extent that this is true, the nature of the system is a most powerful nonspecific commonality that transforms specific clinical interventions into general clinical outcomes. Therapeutic action will spread throughout the system so that it matters little how or why or where the initial change was brought about. In this way, the interrelated elements of the clinical situation will forge common outcomes from what were, initially, different approaches. We will explore in chapter 10 the extent to which this is true.

There is another reality of this clinical situation that tends to produce common outcomes. The nature of the system is such that in actual clinical practice it is hard, if not impossible, to restrict therapeutics to one port of entry alone. This "impurity" of approach is not due to any lack of trying on the part of practitioners, who work hard to direct their efforts into the one port of entry designated by their chosen approach. But the system does not allow for absolute purity. For instance, if one is therapeutically focused on the mother's fantasy life (Mrep) as the privileged port of entry, the actual interaction with the baby (Bact <-> Mact) will of necessity intrude frequently, whether for feeding, changing, calming, paying attention to, or a coda of play. To ignore the interaction would be artificial and bad therapy, the interaction might end the session on practical grounds anyway. Or from the other side, if one's approach is primarily interested in the overt interaction and not at all in the mother's representational world, one will constantly be taken unawares by the profusion of fears, fantasies, memories, and so on, evoked by the parent-infant encounter. Again, ignoring these factors is therapeutically perilous, if not impossible. The therapist is forced to cross and recross the boundaries between the interpersonal and the intrapsychic. Similarly, regardless of the therapist's persuasion, the therapy is simultaneously an individual psychotherapy (with the primary caregiver), a couples therapy (with the husband and wife), and a family therapy (with the triad), either all at the same time or in sequence.

In spite of these difficulties in holding strictly to traditional perspectives and techniques, and in spite of the inevitable impurities in each approach, one element—that is, one port of entry—is privileged and receives most of the therapeutic attention and action.

Theoretically and technically, the situation seems to be quite complex, even messy. And so it is, as measured by the standards of other therapies with other populations. (It is compounded by the unavoidable confusion between therapeutic change and developmental change.) This situation introduces a theme that will reappear over and over in this book. What look like impurities, difficulties, messiness, oddities, and outright failures from standard perspectives are, in fact, intrinsic to the parent-infant clinical situation. It is not a compromised normal clinical situation. It is a different clinical situation, with its own imperatives and opportunities. It must be seen on its own terms, not as an imperfect or pale application of another established therapy. Let us now proceed to explore "its own terms."

hereafter, whenever the word mother is used, it will mean the primary caregiver, except when otherwise specified. I use this shorthand because it is overwhelmingly the case that the mother is the primary caregiver.

CHAPTER 2

The Parents' Representational World

THE REPRESENTATIONAL world of the parents is the first element of the clinical situation to be examined. The parents representations have played a key role in the history of parent-infant psychotherapies influenced by psychodynamic considerations. The parents' representations of the baby and of themselves-as-parents may be given the highest priority in the mind and practice of the therapist, or they may be more or less ignored. In either case, this mental world exists and plays an important role in determining the nature of the parents' relationship with the baby. It is useful to think of the clinical situation in terms of two parallel worlds: the real, objectifiable external world and the imaginary, subjective, mental world of representations. There is the real baby in the mother's arms, and there is the imagined baby in her mind. There is also the real mother holding the baby, and there is her imagined self-as-mother at that moment. And finally, there is the real action of holding the baby, and there is the imagined action of that particular holding. This representational world includes not only the parents' experiences of current interactions with the baby but also their fantasies, hopes, fears, dreams, memories of their own childhood, models of parents, and prophecies for the infant's future.

But what are such representations made of? How are they organized and how are they formed? No one knows exactly. They remain largely mysterious.1 Rather than explore the nature of these representations here, I will defer that discussion until chapter 5, on the infant's representations, where we can proceed with a cleaner slate, since we will be trying to understand such representations as they develop in the infant. Until then, we can assume that we know well enough what we mean that we can proceed.

One preliminary comment, however, is needed. I will assume that these representations are mostly based on and built up from interactive experience—more precisely, from the subjective experience of being with another person. Accordingly, I will also describe these representations in terms of schemas-of-being-with. The interactive experience can be real, lived experience, or it can be virtual, imagined (fantasized) interactive experience. There is, however, always an interaction somewhere underneath. The reasons for this insistence on an origin in interactive experience are several. Object-related representations are not formed when the outside is taken inside, as is suggested by such terms as internalization and introjection. They are formed from the inside, on the basis of what happens to the self while with others. It is in this sense that these representations are not of objects or persons (now inside), or images, or words; they are of interactive experiences with someone. (The representational world is probably more like a montage of film clips than a collage of photographs or words.) I will assume that this is equally true when we speak of a parent's wishes, dreams, fears, and fantasies for their infant or for the self-as-parent. These, too, form around real or imagined pieces of interactions, as we shall see. It is with these reasons in mind that I refer to both representations and schemas-of-being-with.

As a provisional help. I will adopt the following terminology. It will be revisited in chapter 5.

1. A schema-of-being-with is based on the interactive experience of being-with a particular person in a specific way, such as being hungry and awaiting the breast or bottle or soliciting a smile and getting no response. It is a mental model of the experience of being—with—someone in a particular way, a way that is repetitive in ordinary life.

2. A representation-of-being-with is a network of many specific schemasof-being-with that are tied together by a common theme or feature. Activities that are organized by one motivational system are frequently the common theme—for example, feeding, playing, or separation. Other representations are organized around affect experiences; they may be networks of schemas-of-being-sad-with or happy-with, for example. Yet other representations are assemblies made up of many representations that share a larger commonality such as person (all the networks that go with a specific person) or place or role. Representations thus are of different sizes and hierarchical status. I will make no attempt here to distinguish these or to signal the nature of the commonality that organizes the networks; these features can, I believe, be intuited from the context.

A Brief Historical Perspective

The conviction that the mother's representations can influence how she acts with her infant is as old as folk psychology. And for almost a hundred years the psychodynamic literature has commented richly on such influences as yet another example of the pervasiveness of conflictual themes in all domains of life, including the parent-infant relationship...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part I THE CLINICAL SYSTEM IN PARENT-INFANT PSYCHOTHERAPY

- Part II THERAPEUTIC APPROACHES IN PARENT-INFANT PSYCHOTHERAPY AND THEIR COMMONALITIES

- Part III SYNTHESIS

- REFERENCES

- INDEX