Attachment Theory

As research began to inform the understandings of grief, Bowlby’s theory of attachment (1969, 1973) proved to be especially relevant. Bowlby observed young children who were separated from their parents and described regular patterns of behavior that occurred in response to the separation. He ultimately applied his observations and theories about attachment and separation to bereavement, comparing grief after the death of a loved one to the separation distress that children demonstrated when removed from their parents. He proposed that when a primary attachment figure dies, the “affectional bond” is broken, resulting in grief (1970). Thus, grief was described as the response to a broken attachment bond.

Bowlby’s view of attachment was influenced considerably by primate research conducted by Harlow (1963), whose descriptions of infant monkeys’ responses to separation from the mother paralleled Bowlby’s descriptions of the separated children in his studies. These same responses were also seen in other animal species, such as birds and other mammals. Bowlby concluded that the attachment behavioral system had developed through natural selection to discourage the prolonged separation of an infant from the primary attachment figure(s) in order to increase the chances of survival. This inclusion of the ethological (biological) origins of attachment was unique during a time when the psychoanalytic school was the primary approach of those who were trained in psychiatry. The implication for the biological underpinning of this model was the conclusion that the grief response (a form of separation distress) was an extension of the attachment system, and thus had also evolved as a process to ensure safety and survival. However, the assumption that grief was the response to a broken attachment bond was challenged when later bereavement research demonstrated that the majority of bereaved individuals actively seek out and maintain an intangible relationship (referred to as a continuing bond) with their deceased loved ones (Field, Gao, & Paderna, 2005; Klass, Silverman, & Nickman, 2014). The implication of this research was that the attachment bond is not necessarily broken when a loved one dies. Thus, there needed to be further exploration of what actually triggers the grief response.

Bowlby (1969) posited that early-life attachment experiences lead individuals to form “working models” of the self and of the world; for example, a normal working model based upon secure attachment represents the world as capable of meeting one’s needs and provides a sense of safety and security. Bowlby also suggested that loss can threaten these working models, leading to efforts to rebuild or restructure one’s working models to fit the post-loss world. Building upon Bowlby’s work, Parkes (1975) extended the concept of the “internal working model” to that of the “assumptive world,” which he stated was a “strongly held set of assumptions about the world and the self, which is confidently maintained and used as a means of recognizing, planning, and acting” (p. 132), and that it is “the only world we know, and it includes everything we know or think we know. It includes our interpretation of the past and our expectations of the future, our plans, and our prejudices” (Parkes, 1971, p. 103).

The Assumptive World

Parkes (1971) stated that the assumptions individuals form about how the world works are based upon their early life experiences and attachments. He also emphasized that experiencing a significant loss can threaten one’s assumptive world. In her extensive work that examined the construct of the assumptive world in the context of traumatic experiences, Janoff-Bulman (1992) stated that expectations about how the world should work are established earlier than language in children, and that assumptions about the world are a result of the generalization and application of early childhood experiences into adulthood. The assumptive world is an organized schema reflecting all that a person assumes to be true about the world and the self; it refers to the assumptions, or beliefs, that create a sense of security, predictability, and meaning/purpose to life. This description resonates with Bowlby’s descriptions of the development of the attachment system to ensure a sense of safety in the individual and would suggest that the attachment system and the assumptive world construct are formed through similar mechanisms and are probably interrelated. The assumptive world is most likely informed and shaped as part of the attachment system, and the assumptions that are formed are deeply ingrained into the fabric of how individuals live their lives and interpret life events.

Janoff-Bulman (1989, 1992) suggested that there are three primary categories within the assumptive world, each of which of which is comprised of several assumptions. The three main categories are:

- Benevolence of the world—in general, this category consists of how an individual perceives the world in an overarching sense, and also the expectations of benevolence of others.

- Meaningfulness of the world—this category involves people’s beliefs about the distribution of outcomes, including expectations of fairness and justice, perceived control over events, and the degree to which randomness is explainable in the course of events.

- Worthiness of the self—the view of how an individual perceives the ability to respond to events, and to act in ways that ensure self-protection and control over life events.

In further exploration of the assumptive world construct in various scenarios, we might suggest that there indeed may be three overarching/main assumptions, but these assumptions will be predicated upon how an individual has come to view the world, self, and others through formative experiences. Thus, the view of others may not incorporate a primary sense of benevolence. The view of the world may not be one that has a sense of justice or predictability. Finally, the view of self may not include an assumption that the self is worthy or capable of controlling or responding to adverse events. Thus, the revised working model of the assumptive world may involve assumptions that are not generalized for everyone in the same way; however, the basic assumptions may center around the same concepts. So, our assumptive world may be composed of:

- How we tend to view others and their intentions.

- How we believe the world should work.

- How we tend to view ourselves.

In this version of the construct, there is allowance for individuals who have grown up in a world where they have not known safety, or where foundational individuals in a person’s life have not been well-intentioned, or the view of self has been mirrored in a way that does not affirm the individual’s worth, capacity, or value.

Janoff-Bulman (1992) stated that our basic assumptions about how the world should work can be shattered by life experiences that do not fit into our view of ourselves and the world around us. Neimeyer, Laurie, Mehta, Hardison, and Currier (2008) discuss events that “disrupt the significance of the coherence of one’s life narrative” (p. 30) and the potential for erosion of the individual’s life story and sense of self that may occur after such events. What is apparent is that the experience of a significant life event that does not fit into our beliefs can throw us into a state of disequilibrium. Coping, healing, and accommodation after such experiences are part of a greater process that individuals undertake in an effort to “re-learn” their assumptions about the world in light of confrontation with a reality that does not match their existing expectations or assumptions (Attig, 1996). It is important to note that the assumptive world is more than a cognitive construct; these assumptions exist at the very core of what in life provides us with a sense of meaning, purpose, and security. Each category of assumption will have cognitive aspects, but will also incorporate social, spiritual, emotional, and psychological components as well.

In the aftermath of significant loss experiences, the core beliefs that comprise our assumptive world are challenged, and the entire structure that we have built our lives upon begins to crumble. The hopes, expectations, and predictions we had in place are now rendered irrelevant and useless in light of the reality that now presents itself to us. Those assumptions, which have kept us steady and have given coherence to our lives, now seem like naïve illusions. The realization of how little control we have over what happens to us becomes blaringly evident. The glass shatters. There is no going back; the way the world made sense before and the expectations and beliefs that we deeply held about ourselves and others are no longer salient. Losing one’s assumptions about the world means the loss of safety, logic, clarity, power, and control (Beder, 2005). There is an overwhelming sense of disequilibrium and disorientation that occurs while we flounder, trying to navigate in a new, unfamiliar reality. In essence, we are grieving the loss of our assumptive world, and our grief (although painful and disorienting) provides us with the process by which we will grapple with the assault on our most deeply held assumptions and beliefs to eventually rebuild a new assumptive world that will be able to take into account the lived experience that catapulted us into this uncharted territory. A central theme of this book is that grief is a process that is both adaptive and necessary in order to rebuild the assumptive world after its destruction from significant loss experiences.

The Dual Process Model

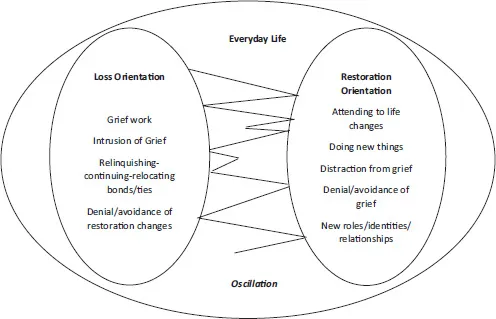

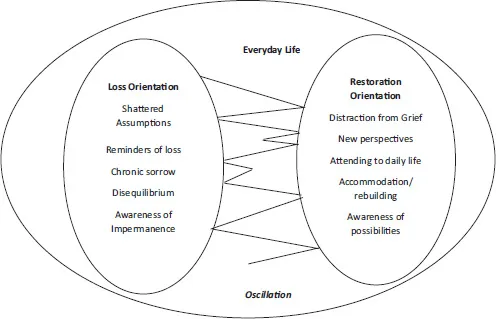

Through their research with bereaved individuals, Stroebe, Schut, and Stroebe (2005) proposed the Dual Process Model of grief. In this model, the grieving process is described as an oscillation between immersion in the loss experience (loss orientation) alternated with the focus upon the aspects of daily life, adjustment, and functioning (restoration orientation), with both processes encompassing the totality of grief (see Figure 1.1). Interestingly, in her descriptions of responses to traumatic events, Janoff-Bulman (1992) also posited oscillation between numbness (often described as avoidance of the event) with confrontation (and re-traumatization) as part of the attempt to reconcile a seemingly senseless event that has happened with a belief system that hinges upon benevolence and meaning. This description is very similar to the Dual Process Model of coping with grief, suggesting the need to oscillate between avoidance of the loss and focusing on everyday functioning alternated with confronting the loss and its effects. While the Dual Process Model was based upon research with individuals whose loss involved the death of a loved one, the model is readily applicable to grief in non-death loss experiences (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.1The Dual Process Model of Coping with Bereavement

Figure 1.2The Dual Process Model for Non-Death Loss and Grief

In a review of empirical literature, Stroebe et al. (2005) discussed the relationship between attachment style and how individuals may oscillate between loss orientation and restoration orientation. According to Bowlby (1973, 1980), individuals with a secure attachment style have positive mental models of being valued and worthy of others’ concern, support, and affection. The case could be made that individuals with a secure attachment style may indeed be aligned with Janoff-Bulman’s original description of the three assumptions in the assumptive world construct; it would make sense that people whose attachment pattern is mostly secure will tend to see others as generally benevolent, to see the world as meaningful, and to view themselves as competent, worthy, and valued. Those whose attachment style is not secure will have assumptive worldviews that reflect views of others, the world, and themselves in ways that may not be as positive, and their ways of coping with significant losses would be consistent with specific aspects of insecure/anxious attachment. For example, individuals whose attachment style is primarily anxious/ambivalent may tend to ruminate about their loss experiences, have difficulties adjusting to change, experience higher levels of distress when losses are encountered, and are more prone to depression (Bowlby, 1980; Wayment & Vierthaler, 2002). In the Dual Process Model, these individuals are more likely to spend more of their time and energy in the loss orientation, with much less time venturing into the restoration orientation aspects of grief (Collins & Feeney, 2000). Individuals whose attachment style is primarily anxious/avoidant often see significant others as being unreliable, or desiring too much intimacy, and they tend to disengage from their attachment systems and may not experience emotional distress. The consequence of actively avoiding affective reactions is the possibility of increased levels of somatic symptoms. Thus, those with a predominantly anxious/avoidant attachment style may report little emotional distress when a significant loss occurs, and they may predominantly gravitate towards the restoration orientation aspects of grief, with a tendency to have more bodily symptoms in the process (Pennebaker & Beall, 1986).

The Social Context of Loss

The fact that our attachment system and assumptive world form our core beliefs, views, and expectations about life is a strong indicator of our social nature and the importance of social interactions to us, beginning when we are born and continuing throughout our lives. The underlying foundation of attach...