- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book is about the choices black French citizens make when they move from Martinique and Guadeloupe to Paris and discover that they are not fully French. It shows how ethnic activists in the Afro-Caribbean diaspora organize to demand what has never been available to them in France.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Black Skins, French Voices by David Beriss in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

FINDING CREOLE IDENTITIES IN MARTINIQUE AND PARIS

THE VIEW FROM THE HÔTEL L’IMPÉRATRICE, FORT-DE-FRANCE, MARTINIQUE

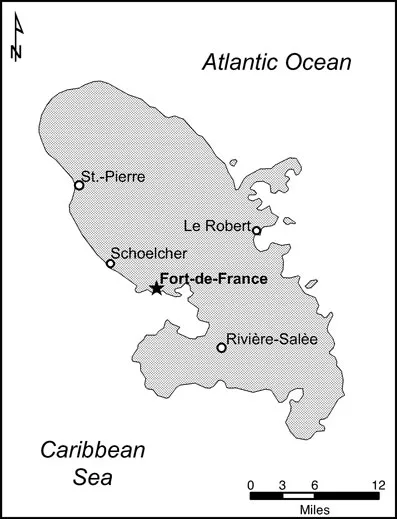

In September 1988, I was invited to speak at a luncheon of the Fort-de-France Rotary Club. Since I was beginning ethnographic field research in Martinique (see Fig. 1.1), I jumped at the chance to meet some of the city’s business elite and eat a decent meal. The event took place in the restaurant of the Hôtel L’Impératrice, named for Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte’s Martinican wife, Joséphine de Beauharnais, who is suspected of persuading her husband to reinstate slavery on the island. The hotel lobby—with its newsstand, tobacconist shop, café, and open view of the Savane park with its statue of Empress Joséphine, beheaded by locals in a sign of their contempt (see Fig. 1.3)—seemed like the kind of place where colonial intrigues of the sort described by Graham Greene in his novels might have taken place.

Before lunch, the ethnically mixed but all-male crowd gathered for an apéritif on the fourth-floor balcony. Expressing curiosity about my research, a white Frenchman warned me of the mystery and paradox of the French Antilles. Before they moved from Paris to Martinique, his wife went to see a voyant (fortune-teller) seeking insight into the family’s fate in its new overseas endeavor. He told me this story with apparent embarrassment over his wife’s breach of proper French rationality. The fortune-teller’s powers to see into their fate, he said, were limited by a geocultural haze that, for her, surrounded Martinique. Somewhere between Africa and Europe, someplace in the Americas but not of the Americas, the voyant told his wife, adding that she could not make sense of their destination. If Martinique is not quite a distant slice of France, it is not an independent Caribbean nation either.

Figure 1.1 Martinique.

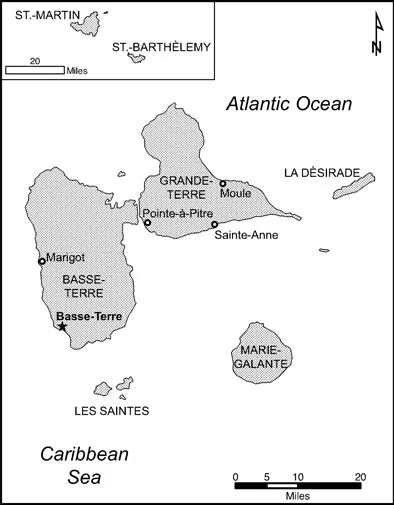

Figure 1.2 Guadeloupe.

Figure 1.3 Beheaded statue of Empress Joséphine, Fort-de-France, Martinique.

PICTURE BY MARTINIQUE-PHOTOS.COM.

PICTURE BY MARTINIQUE-PHOTOS.COM.

At the head table, I was seated with the black manager of a French utility company, an East Indian architect from Paris, an elderly black Martinican psychiatrist, and the light-skinned, possibly white club president. The calalou de crabe, a kind of thin gumbo with herbs and crabmeat, was made magical with the addition of a slice of piment, or scotch bonnet pepper. As the meal proceeded, the club president invited me to speak.

I told them of plans hatched in distant New York, something about how Martinican and Guadeloupan immigrants in Paris organize amid controversy over immigration and about their efforts to assert their distinct cultural identity in metropolitan France. When I finished, the room erupted in a lively forty-five-minute debate about Antilleans in France and the “immigrant” problem there. Many insisted that I had made a fundamental mistake. Because Martinicans are already French citizens, they asserted, they cannot be immigrants in France. They are simply moving within their own country and should be referred to as internal migrants. The distinction was important to them—immigrants, one member heatedly claimed, are foreigners, usually Arabs, who “bring their Ramadan and other crazy stuff.” Martinicans are more like Corsicans, cultural insiders with a few colorful particularities. Martinicans and Guadeloupans work, they noted, in the same kinds of public service jobs that Corsicans used to hold. I asked, “But don’t Antilleans suffer from racism in France?” I had read, for instance, that public housing authorities stigmatized them and applied quotas limiting their numbers. The Rotarians agreed that this had happened but insisted it was only an unfortunate mistake or misunderstanding. Arabs are the only population with problems in France, they asserted.

After lunch, four or five club members continued the discussion. One, an elderly béké (the local term for white plantation owners and their descendants), told me a story about a Frenchman he met sometime after World War II, an anthropologist who wanted to know about race relations in the Antilles (Leiris 1955). A black Martinican told the researcher that he, as a white metropolitan Frenchman, would have difficulty understanding the finer points of relations between the descendants of slaves and local whites. “We live here together,” the black man told my predecessor, “but the békés do not invite us to socialize with them and we do not invite them to socialize with us. Our children do not play together. Yet we respect each other. You metropolitan whites, on the other hand, expect us to socialize with you. But you really see us as inferior.” What the black man told the French anthropologist, the béké added with a grin, is still the way things are here.

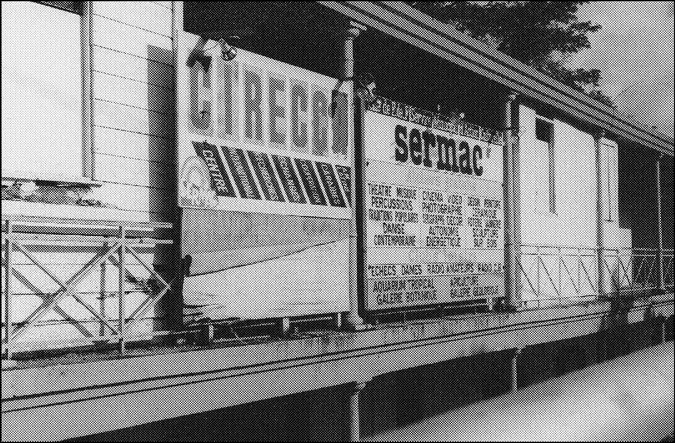

At the research center—part of a former colonial hospital turned municipal arts center where I lived (see Fig. 1.4)—I met Marlene, a young black Martinican student who worked there as a part-time administrator. When I told her about the Rotarian lunch and the béké’s picture of Martinican life, she scoffed. “The békés don’t respect us,” she said. “They think everything is fine, but their racism has ruined this society.”

ANTILLEANS AND THE “IMMIGRANT” PROBLEM IN FRANCE

This project began with a misunderstanding. I had lived in Paris for a few years in the early and mid-1980s. I witnessed the increasing violence and harassment against immigrants, including police shootings, beatings by gangs of “skinheads,” and everyday discrimination in jobs, housing, and schools. This had become improbably personal. I had always been a beneficiary of white invisibility in the United States, yet in France I often failed to pass as an American. Something about me proclaimed “Arab” to French police. They routinely stopped and frisked me while checking my papers and asking me hostile questions, interrogations that did not happen to other Americans. One day in a café in an upscale neighborhood, sharing coffee with some French friends, I failed to recognize myself in a mirror—who is that swarthy, slightly suspicious foreigner, I wondered. Then with sudden recognition came shock. I had begun to see myself as French people did. What about real immigrants? What did they see in the mirror?

Figure 1.4 Municipal Arts Center, Fort-de-France, Martinique.

Many immigrants could see that France was having trouble coming to terms with itself as an increasingly diverse society. The discrimination, harassment, and racism I had observed resulted in the growth of ethnic activism among immigrants and the development of immigrant rights coalitions and antiracist organizations, including, most notably, SOS Racisme, known for its evocatively named leader, Harlem Désir, and for the colorful antiracist badges it made ubiquitous in France. Shaped like an upturned hand to signal a halt to racist violence, they were inscribed with the slogan “Hands off my pal” (Touche pas à mon pote). SOS Racisme and other organizations used creative tactics, including cross-country marches that grabbed the attention of the press and the country. They demanded an end to racism and recognition of their cultural differences. France, they argued, must no longer be thought of as a culturally homogeneous nation. “France is like a moped; to advance it needs mixture” was a popular slogan at the time (mopeds, which are popular in Europe, run on a mix of gasoline and oil). Martinicans and Guadeloupans were prominent in these demonstrations and had assumed leadership roles in some of the largest immigrant rights and antiracist coalitions. Harlem Désir, for instance, was born in Paris of a Martinican father and French mother.

As citizens, Antilleans are not classified as immigrants and their prominence in these movements was little noticed at the time. Approximately 337,000 Martinicans and Guadeloupans live in metropolitan France, which, if they were counted as immigrants, would make them the fifth largest immigrant group, after Algerians, Portuguese, Moroccans, and Italians.1 Antilleans would seem to be cultural insiders. They come from islands that have been part of France for over three centuries, are educated in French schools, speak French, and are deeply entrenched in French culture and society. Since they are predominantly Catholic, unlike Muslim North Africans, their religion should not stand in the way of assimilation. Recruited starting in the 1960s to work in public service jobs available only to citizens, they successfully worked in positions that, as the Rotarians had noted, Corsicans held in the past. If Antilleans faced neither cultural barriers nor legal limitations on their participation in French society, why were they now asserting difference and demanding recognition from the French state? If they were “really” French, what difference did they want to have recognized? With their centuries-long ties to French society, what did Antilleans see when they looked in the French mirror?

“But aren’t these people black?” Asked in a tone that suggested it was more answer than question, this query, posed by friends and colleagues in the United States, haunted my efforts to make sense of Antilleans’ cultural position in France. Although there could be no doubt that something called racism existed in France (why else would there be antiracist organizations?), there were few attempts in the early 1990s to discuss immigration or ethnicity in explicitly racial terms. Unlike Britain and the United States, France had no “race relations” literature in the social sciences. It had long been asserted that what distinguished French culture from its European neighbors was the humanist ideal according to which anyone could become French simply by accepting French culture (see Brubaker 1992; Feldblum 1999). Being French was based, as the political philosopher Ernest Renan (1992, 55) famously asserted, on consent to live in community. He explicitly rejected the idea of a French nation formed from descent or race. French society existed in a world of cultures, not races. If there was racism in France, it followed that this was a racism without races (Balibar 1991; Stolcke 1995).

At the same time, Antilleans come from societies where ideas about racial difference form an important organizing principle of social life (Giraud 1979; Murray 1997). The role of race in the French Antilles is comparable to the role it plays in the rest of the Caribbean (Alexander 1977; Martinez-Alier 1989; Segal 1993; Yelvington 1995). Antilleans may deny the relevance of race in defining who they are; one sociologist wrote that his father, “a black man from Guadeloupe,” responded to harassment in France over his color or origin by pointing out, “I have been French since 1635, long before people from Nice, Savoy, Corsica or even Strasbourg” (Giraud 1985, 585).2 Yet the very articulation of such challenges and responses implies a perception of race as visual difference from some preconceived notion of who is French. Does this mean that race is somehow hidden, but present all the same, in French culture?

Immigrant activism, by Antilleans and others, threatened the very idea of a homogeneous French culture. The emphasis on making cultural “mixture” central to French identity among immigrant activists—what we usually refer to as “diversity” in the United States—was something new for French society in the 1980s and 1990s. The French nation had been built on the idea of a unified culture, shared by all citizens. In fact, making people adopt a single culture—turning peasants into Frenchmen—was a central objective in both France and the colonies of its former empire (Weber 1976; Bancel et al. 2003). I began to think that the “immigrant problem” was not about immigration. It was a “French problem,” defined by French ideas about different cultures, by hidden assumptions about race and French policies toward people designated as different, as “immigrants.” The French had made immigrants into the “immigrant problem,” as Jean-Paul Sartre (1954) would have said, creating a category defined more by French social concerns than by the lives of the people thus categorized.

The demands that Antilleans and other immigrants made for cultural recognition ignited a national debate in France about the meaning of being French and the organization of French society. The very structure of the French state has long been marked by the assumption that class and class conflict are fundamental to the organization of society. Public policy, as well as social science, has been organized around the idea that le social, as class-related policy debates are known in France, was the basic reality behind politics. Immigrant demands for cultural recognition, the formation of recognizably distinct cultural communities, and the rise of a kind of multiculturalism in French society has, since the 1980s, become central to French political life, raising the possibility that culture—le culturel—may be in the process of replacing the social as the central structuring principle of French society.

Antilleans provided an ideal group for testing this hypothesis. Despite their insider status, these black French citizens had determined to demand something that had never been available in France—the right to be full citizens and, at the same time, maintain a distinct identity. This demand seemed especially ironic in the Antillean case, since in 1946 Martinique and Guadeloupe had explicitly opted to become departments of France, rather than independent countries. Yet having once chosen assimilation, postcolonial Antilleans in France now desired difference. Because legally they were not immigrants, their turn toward cultural activism cannot be attributed to their status as “foreigners.” The ways Antilleans worked toward asserting their distinctiveness—drawing on notions of Antillean and French culture—promised to provide useful insights into the meaning of the concept of culture in a postcolonial world.

In both Martinique and metropolitan France, government officials and all sorts of activists regularly deploy ideas about culture in order to make claims about who belongs in various groups and to argue for public policies. They often invoke the term “culture” in ways that seem to reflect anthropological usage. Culture, when used in France, covers a multitude of objects, from art to peasant life and rituals to housing and festivals associated with the industrial working class. It is used in ways that resemble a reified version of the anthropological notion of a total way of life, in which people do not “have” culture so much as they are had by it. While “culture” is often used to link a group of people with a set of practices and a territory, the manner in which that linkage is made and the content and meaning of any given set of practices is still controversial in France. This is especially the case in discussions of the cultures of immigrants, whose behavior is often held up by French intellectuals against an ideal type of the culture of their societies of origin, and of immigrant youth, who are frequently referred to as being entre deux cultures, between two cultures (Hargreaves 1996; Wacquant 1993). Because the French term is the same as the English word “culture,” in what follows I will use italics when I am referring to the French vernacular.

The fact that the very terms and concepts of traditional anthropological analysis—...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Series Editor Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 FINDING CREOLE IDENTITIES IN MARTINIQUE AND PARIS

- 2 WHAT IS THE PRICE OF FRENCHNESS?

- 3 BETRAYED ANTILLES, BROKEN FRENCH PROMISES

- 4 BOUDIN, RHUM, AND ZOUK: PERFORMANCE AND CULTURAL CONFRONTATION

- 5 CAN MAGIC FIX A BROKEN CULTURE?

- 6 IN THIS WORLD, BUT NOT OF IT

- 7 CONCLUSION: CREOLIZING FRANCE

- Glossary

- References

- Index