- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In this book, Charles R. Acland examines the culture that has produced both our heightened state of awareness and the bedrock reality of youth violence in the United States. Beginning with a critique of statistical evidence of youth violence, Acland compares and juxtaposes a variety of popular cultural representations of what has come to be a perceived crisis of American youth. After examining the dominant paradigms for scholarly research into youth deviance, Acland explores the ideas circulating in the popular media about a sensational crime known as the "preppy murder" and the confession to that crime. Arguing that the meaning of crime is never inherent in the event itself, he evaluates other sites of representation, including newspaper photographs (with a comparison to the Central Park "wilding"), daytime television talk shows (Oprah, Geraldo, and Donahue), and Hollywood youth films (in particular River's Edge). Through a cultural studies analysis of historical context, Acland blurs the center of our preconceptions and exposes the complex social forces at work upon this issue in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Acland asks of the social critic, "How do we know that we are measuring what we say we are measuring, and how do we know what the numbers are saying? Arguments must be made to interpret findings, which suggests that conclusions are provisional and, to various degrees, sites of contestation." He launches into this gratifying book to show that beyond the problematic category of "actual" crime, the United States has seen the construction of a new "spectacle of wasted youth" that will have specific consequences for the daily lives of the next generation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Youth, Murder, Spectacle by Charles R Acland in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Youth

1

Youth in Crisis

We are simply trying to bring to light the texture of a discourse, the texture being composed not only of what was said, but of all that was needed for it to be said.

—Philippe Riot, "The Parallel Lives of Pierre Riviere"

On the occasion of International Youth Year 1980, the General Conference of UNESCO in Belgrade produced a comprehensive report entitled Youth in the 1980s. Comparisons with the first UNESCO report on youth, in 1968, are interesting. As the authors point out, the key words of the 1968 report were "confrontation-contestation," "marginalization," "counter-culture," "counter-power," and "youth culture." In contrast, the 1981 report suggests that "the key words in the experience of young people in the coming decade are going to be: 'scarcity,' 'unemployment,' 'underemployment,' 'ill-employment,' 'anxiety,' 'defensiveness,' 'pragmatism' and even 'subsistence' and 'survival'" (UNESCO 1981, 17). The assertive terms of the first report depict an instance of vitality, possibility, and ambition. At that time, a significant population of young people, most pronounced in Europe and North America, had attained a privileged social position economically, politically, demographically, and intellectually. Youths were set to begin deploying those powers for confrontation; this was their arrival on the political scene, making demands of representation and becoming a mobilized social energy. However wary mainstream politics remained, youth was indisputably a significant force to be reckoned with. That moment has passed. The terms chosen by UNESCO to characterize the youth of the then-approaching decade of the 1980s demonstrate a striking prescience. UNESCO predicted correctly that "if the 1960s challenged certain categories of youth in certain parts of the world with a crisis of culture, ideas and institutions, the 1980s will confront a new generation with a concrete, structural crisis of chronic economic uncertainty and even deprivation" (p. 17).

This structural crisis of youth in the United States throughout the 1980s escalated rapidly to a point that is now commonly recognized as one of unprecedented social strife and disparity between social factions. And even though some contest the historical uniqueness of this predicament, there is something significant about the broad acceptance of this description; it is now part of popular common sense that something has gone wrong with today's youth. For instance, a joint commission report of the American Medical Association (AMA) and the National Association of State Boards of Education (NASBE), Code Blue: Uniting for Healthier Youth (1990), designed to alert teachers and medical professionals to the seriousness of the situation, concludes that "never before ... has one generation of American teenagers been less healthy, less cared-for or less prepared for life than their parents were at the same age" (Lewis 1990, A21). This is a remarkable and alarming assertion. The vigor of the young has traditionally provided higher aspirations for the future. The "next generation" as a rhetorical concept has carried the impression of vision and hope. And yet now, the report claims, for ostensibly the first time in this century, not only does the promise of "a better tomorrow" seem absurd—the young also cannot expect even the same quality of life as their parents.

The AMA-NASBE commission report points out that we are living in a situation in which more that 20 percent of American children live below the poverty line. For African-Americans the figure is 45 percent and for Mexican-Americans, 39. The U.S. Bureau of the Census indicates that youth is the most heavily unemployed segment of the population. Unemployment for white males between sixteen and nineteen is 15.4 percent, and for females it is 13.4 percent; for black males, unemployment reaches 34.5 percent, and for females it is 34.9 percent (U.S. Bureau of the Census 1989, 379). Furthermore, the available jobs are heavily exploitive, mostly part-time with few, if any, benefits. This situation reflects a shift in which the young have become increasingly central to many service industries as a cheap, short-term, unskilled labor force.

Even in the context of indisputable economic strife, the AMA-NASBE commission concludes that something is distinct about the conditions of today's youth. The commission argues that unlike the past, in which physical illness was the primary threat to the young, today the problems are primarily behavioral. Here the commission refers to the high rates of teenage pregnancy, sexually transmitted diseases, alcohol and drug consumption, suicide, alcohol-and drug-related deaths, and violent crime as measures of the threats to contemporary youth. Read through the arenas of sex, drugs, and violent crime—the unholy trinity of misguided youth—we are presumably in a situation in which, despite the opportunities and efforts of concerned citizens, something is failing.

The empirical validity of these measures of a behavioral crisis of youth could be debated at a number of different levels. This is an ever-present problem for the positivist social critic: How do we know that we are measuring what we say we are measuring, and how do we know what the numbers are saying? Arguments must be made to interpret findings, which suggests that conclusions are provisional and to various degrees are sites of contestation. However, the question of the accuracy of sociological measures tells only part of the story. Of crucial importance is the manner in which such conclusions are deployed; the AMA-NASBE document intended to serve a public information function, and its conclusions cannot be seen outside of that purpose. Its audience was supposed to be primarily those who deal with young people in a professional capacity, such as teachers and social workers. Sometimes pointing to the structural impossibilities of unemployment, a failing education system, and limited health services, the AMA-NASBE commission also focuses on parental neglect of the young as a principal impetus of their destructive impulses and actions. While the report provides a description of a social phenomenon, it also tells of the attention paid to that phenomenon, or rather to that set of measures and judgments that purport to indicate the existence of a crisis. Whether or not the situation is historically unique, it is certainly being taken as such.

This is the context in which American youth came under scrutiny in the 1980s. And "youth in crisis" took many forms. Whether it was The Oprah Winfrey Show on "Teens in Crisis," Tipper Gore's book Raising PG Kids in an X-Rated Society (1987), an NBC prime-time news special entitled "Bad Girls," or a Cinemax documentary called Why Did Johnny Kill?, there was definitely a vociferous public debate concerning the nature of contemporary youth. Certainly, after Brenda Spencer fired her semiautomatic rifle at her San Diego high school classmates in 1979, killing and wounding eleven people in total, we have seen no shortage of spectacular youth crimes wash through the popular media. Racist youths in Howard Beach, a largely white section of New York, chased and beat three black youths in December 1986, killing one as he ran into the path of an oncoming car. Sixteen-year-old Cheryl Pierson hired a high school classmate, seventeen-year-old Sean Pica, to kill her father in February 1986. Ronald Lampasi, then sixteen, killed his stepfather and wounded his mother in 1983. He claimed to have been acting out a scenario from the fantasy game Dungeons and Dragons. This was followed by concern about the effects of the game, its relationship to satanism, and a number of other murders and suicide pacts whose inspiration was supposedly found in the confusion between fantasy and reality encouraged by Dungeons and Dragons. Los Angeles gang violence provided images of warlike urban conflict throughout the decade, making the "Bloods," the "Crips," and the "drive-by shooting" household words.

As gang violence appeared to move eastward across the country, young murderers seemed to get younger. Britt Kellum was nine when he killed his older brother in 1985 and thirteen when he killed his younger brother. In Florida in 1986, a five-year-old confessed to deliberately pushing a three-year-old off a five-story balcony. In 1992, Amy Fisher, the "Long Island Lolita," tried to kill her lover's wife, sparking an unprecedented amount of coverage, including three made-for-tv movies. And by the summer of 1993, it seemed that no one was immune to the effects of this tide of youth violence when basketball superstar Michael Jordan's father was killed in North Carolina.

Brenda Spencer is particularly important because she reintroduced into popular consciousness a supremely terrifying aspect of contemporary youth violence: meaninglessness. When asked why she committed such an atrocious crime, she replied simply, "I don't like Mondays. Mondays always get me down." The frankness and banality of this explanation—who, after all, would disagree?—were a terrible contrast to the image of her spraying bullets into a schoolyard. How could sense be made of this? Though there were several key precendents to her youthful nihilism—for instance, the 1950s killer Charles Starkweather, particularly as mythologized in Badlands (Terrence Malick, 1974)—Spencer's innovation, as it was popularized, was affectlessness. The Boomtown Rats' hit song "I Don't Like Mondays" gave Spencer and her affectlessness a certain folk hero status, much as broadsheets and songs celebrating criminals had done in previous centuries. The romantic tone of the hit song suggested that the representation of violent youth crime was about to be reinvested as a cultural expression of a displaced generation. What would become fearful throughout the 1980s was, for a brief moment, a weird celebration in popular music.

In 1957, when Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Benjamin Fine published his study of juvenile crime, 1,000,000 Delinquents, he began by citing examples of crimes in which teenagers "kill for thrills." The idea of teenage crime as teenage entertainment suggests that if society alleviates boredom, the problem is solved. And, indeed, Fine's book ends with a series of recommendations for "training schools" and organized leisure activity. Brenda Spencer made this approach obsolete. Calls for increased prison sentences and trying of minors as adults more frequently became the focal point of dealing with youth crime. For instance, during the 1980s it was not unusual to see articles like the one in the Chicago Tribune entitled "Troubled Teens, Big Business" (Kass 1989b). Inside, the author provided helpful "consumer information" for parents who were shopping around for a psychiatric institution in which to commit a "troubled" teenager. The author suggested, among other things, that "parents should visit several units themselves to see how children are treated. They should determine when and why medication, handcuffs, leather straps, four-point restraints and solitary confinement are used to control their children. Does the hospital have specific guidelines on these extreme measures?" (Kass 1989a, 18).

Throughout the 1980s, there was a renewal of old debates, such as the negative influence of rock and roll discussed at the Parents' Music Resource Center hearings, questions of censorship, and toughening of penalties for juvenile offenders, which culminated in debates concerning capital punishment for juveniles. In 1986, the state of Texas executed a murderer who had committed his crime at the age of seventeen, and in 1989 there were twenty-seven juvenile criminals on death row in the United States. The 1980s also witnessed the initiation of contemporary agendas, the most pervasive and powerful of which was the "War on Drugs," which in so many ways modified daily life in America. One unique contribution of this period was the marketing of a home drug-testing unit called DrugAlert. As the final link in the circuit tying domesticity to a national law-and-order campaign, private life became the site of surveillance based upon the presumed activities of the young. As the principal target for the "just say no" campaign, youth were centrally implicated by the War on Drugs as both those who required protection and those who were involved in the criminal activity of drug culture.

Warning labels on food, records and compact disks, art exhibits (see Dubin 1992), and, more recently, television programs constructed a new landscape of everyday danger. It is unclear whether "parental advisories" actually placed additional power into the hands of adults, but such advisories certainly gave the impression of concern and fear about the cultural consumption of the young. The James Bond film License to Kill (John Glen, 1988), after the usual cocktail (shaken, not stirred) of torture and mayhem, ended with a surgeon general's warning about the effects of smoking. There were complaints that the impressionable would see Bond's smoking as an endorsement.

As absurd as this may seem (why no warning about reckless driving or hang gliding?), lifestyle politics became an important arena in which a person's ethical and moral makeup could be displayed and evaluated. Fletcher A. Brothers founded Freedom Village to help troubled youths by restoring the centrality of "Christian virtue" to their lives, and he also produced a syndicated television program. On the air, he would repeatedly describe a young person as "a former satanist and heavy metal music fan." The continuum between the two was assumed by many to be obvious; certain demonized cultural forms allowed for generalized claims about vast populations of fans.

While cultural consumption provided evidence of criminality, criminal youth remained a specific and pivotal instance of the crisis. Juvenile delinquency, an invention of the nineteenth century, has been a prominent social concern since its inception. In the present context, violent youth is particularly visible. For instance, despite a 13 percent drop in the death rate of youths, the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion says that there has been an 11 percent increase in violent deaths of youths since the 1960s (Friend 1988, 1). Firearms kill more than 10 percent of people who die before the age of twenty ("Fatal Shootings" 1989, 27). The AMA-NASBE report points out that homicide is the leading cause of death among African-Americans aged fifteen to nineteen. Between 1983 and 1987, according to the FBI, there was a national increase of more than 22 percent for juveniles arrested for homicide and manslaughter with intent; in Philadelphia alone, youths under eighteen arrested on murder charges increased 90 percent in 1988 (Colimore 1989, A1).

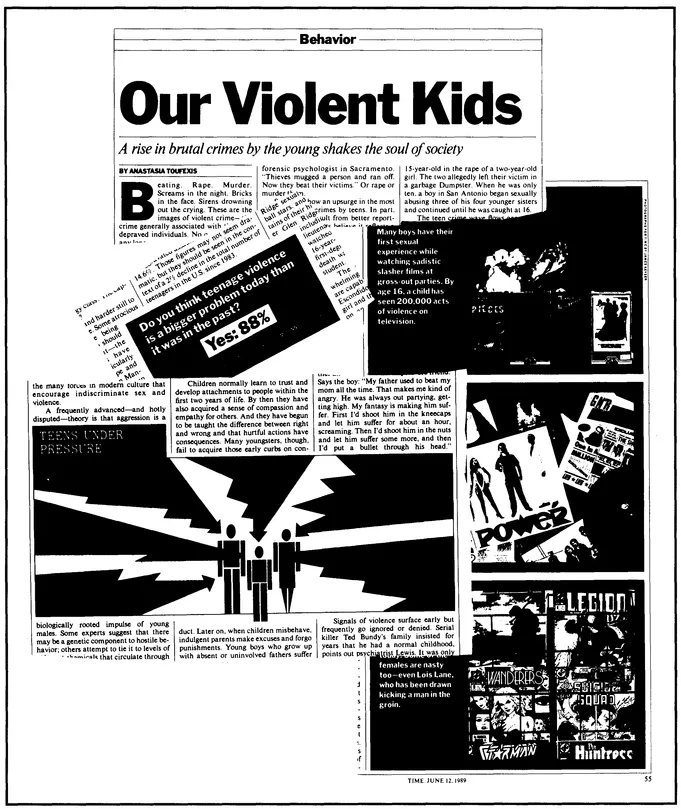

As reported in the popular press, every empirical measure seems to indicate yet another crack in the previously tranquil and sheltered, or so it is presumed, life of the young. A June 1989 Time magazine feature story entitled "Our Violent Kids," in a rather blatant display of alarm, announces that 88 percent of Americans believe that teenage violence is a bigger problem today than in the past (Toufexis 1989, 52; see Figure 1.1). And yet there is significant evidence that contradicts these taken-for-granted measures of crisis. For instance, despite some increases in violent crimes committed by juveniles in the 1980s, the levels are still far below those of the mid-1970s.1 The U.S. Congress (1991, 591) confirms this claim in a 1991 comprehensive report on adolescent health: "Although current rates of arrests for serious offenses by U.S. adolescents may seem high, there is some evidence that the aggregate arrest rates for serious violent offenses and for serious property offenses committed by U.S. adolescents have declined since the mid-1970s." The report's authors do not downplay concern for criminal youth, citing an increase in murder and nonnegligent manslaughter offenses committed by those between thirteen and eighteen years of age. But the report points out that "a large majority of U.S. adolescents commit minor offenses at least once and that a considerable minority of adolescents also commit serious offenses at least once" and that it is only "a small subset of adolescent offenders who commit multiple, serious offenses" (pp. 594-596).

Even though delinquency is still dominated by male youths, the 1980s saw a significant increase in the arrest rates of female youths (p. 597). The aforementioned report indicates that arrest rates for serious offenses in the same period were higher for black adolescents than for their white counterparts and that both groups were higher than other populations, including Native Americans, Asian-Americans and Pacific Islanders (p. 598). The report also cites research that points to combinations of family variables, such as lack of parental supervision, parental rejection, poor parental disciplinary practices, and familial criminal behavior, as the best predictors of juvenile delinquency (p. 603).

These items provide a sketch of the terrain of American delinquency in the 1980s. Patterns of incidence of and involvement in particular crimes are apparent. Without question, there is much to be concerned about, and innovative forms of action are warranted. But these patterns do not indicate uniform increases. Instead, the ample public belief in the increasingly violent nature of American youth must be understood as a felt crisis. In a description of the ideological work of new conservatism, Lawrence Grossberg (1992, 284) characterizes an "affective epidemic" as one that consists of a fetishized mobile site that is "invested with values disproportionate to their actual worth," where in addition to ideological meaning, there is a "daily economy of saturated panics." For present purposes, how these observations about youth crime come to form and support the feeling of a crisis of youth is unpredictable. And yet we need to unearth the mechanisms for the construction of "saturated panics."

We can point, as the report tries to do, to all the missing information. Is the increase in female arrest rates due to changes in criminal behavior or to changes in attitudes toward women in general, leading to the police's willingness to charge young women offenders where they would have previously been released? Is the higher instance of African-American violent crime actually a marker of cultural difference, as some would have us believe, or it is representative of differential policing methods? Or is it an expression of general social despair? If nonnuclear families contribute to a decrease in parental supervision of children, are they then contributing to juvenile crime? Clearly, the move from the "obviousness" of empirical measures to their meaning, to their significance for policy and policing, is always a site of contest. And as these questions suggest, this move toward meaning has particular interest for critics of sexism and racism. A framework is necessary to connect up "evidence" about the world with meanings, solutions, causes, and predictors. When we examine the work evidence is made to do we have insight into that framework. In this respect, issues of race, gender, sexuality, class, and, of course, age are at the very core of the project of understanding the emergence of a commonsense crisis of youth.

Figure 1.1. A Time feature article, 1989.

It is also often the case that youth violence is taken to be symptomatic of other supposed social crises, such as the destruction of the nuclear family, the drug problem, the problems of "inner-city" (read: nonwhite) populations, the plethora of pornography, the failure of public education, and even, as Geraldo Rivera is quick to indicate, the popularity of satanism. The aforementioned Time feature article is exemplary. Along with general information about "our violent kids," the article points to "causes" such as "lack of parental supervision, lenient treatment of juvenile offenders, too much sex in movies, television, and advertising." And some popular "remedies" are suggested, such as "tougher criminal penalties, and greater restraints on showing sex and violence on television, in movies, and in rock-music lyrics" (Toufexis 1989, 57). At the point of virtually every measure of social crisis—race rel...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- PART ONE: YOUTH

- PART TWO: MURDER

- PART THREE: SPECTACLE

- Notes

- References

- About the Book and Author

- Index