![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

The Gastrointestinal (GI) Tract as a Barrier and as an Absorptive and Metabolic Organ

Shayne C. Gad

CONTENTS

Structure

Mucosa

Submucosa

Muscularis

Serosa

Peritonitis

Salivary Glands

Composition and Functions of Saliva

Tongue

Pharynx

Esophagus

Histology of the Esophagus

Anatomy of the Stomach

Histology of the Stomach

Anatomy of the Small Intestine

Histology of the Small Intestine

Anatomy of the Large Intestine

Histology of the Large Intestine

Function

Mechanical and Chemical Digestion in the Mouth

Regulation of Gastric Secretion and Motility

Cephalic Phase

Gastric Phase

Intestinal Phase

Regulation of Gastric Emptying

Role and Composition of Bile

Regulation of Bile Secretion

Role of Intestinal Juice and Brush-Border Enzymes

Mechanical Digestion in the Small Intestine

Chemical Digestion in the Small Intestine

Digestion of Carbohydrates

Lactose Intolerance

Digestion of Proteins

Digestion of Lipids

Digestion of Nucleic Acids

Regulation of Intestinal Secretion and Motility

Absorption in the Small Intestine

Absorption of Monosaccharides

Absorption of Amino Acids, Dipeptides, and Tripeptides

Absorption of Lipids

Absorption of Electrolytes

Absorption of Vitamins

Absorption of Water

Mechanical Digestion in the Large Intestine

Chemical Digestion in the Large Intestine

Absorption and Feces Formation in the Large Intestine

Occult Blood

The Defecation Reflex

Dietary Fiber

References

The GI tract is the greatest of the three major pathways into and out of the body, the other two being the skin and the respiratory tract. It is the great highway through the body, but much more. Like the other two, it is also a major metabolic organ and a major interface of the environment with the immune/lymphatic system.

This work, as a whole, focuses on the specifics of the toxicology of xenobiotics on the GI tract and adverse effects on its structure and function. It is also concerned with a critical appraisal of what we have come to know about the interaction of xenobiotics with this organ system and of the experimental methods and attempts to define those aspects of research that have proven to be productive for further understanding. Within these two broad objectives, the volume focuses on a number of specific aspects of intestinal toxicity. These areas of research reflect the increasing awareness and documentation of the multiple roles of the GI tract’s multiple components, including the well-recognized and major roles of nutrient absorption, of barrier penetration, and of the importance of the intestinal microbiome (the community of commensal microorganisms that inhabit the GI tract). In addition, emphasis is given to the expanding body of knowledge that relates to the intestines as a major metabolic and immunologic organ involved in the synthesis and degradation of both natural and foreign substances. A further dimension is the inclusion of several discussions aimed directly at the function and dysfunction of the human absorptive processes and the effects of microbial flora on these processes.

The differences between model species are also examined in depth in a separate chapter.

A wide range of approaches and methodologies have been employed to evaluate the maturation and functions of the gastrointestinal tract. Because of its unusual morphology, the mouth, intestines, and stomach can be examined in vivo and in vitro by a variety of techniques, each providing different kinds of relevant information and understanding. The expanded availability of both imaging technologies, sensors, and miniature cameras that can transit the GI tract and collect data and images at selected points has vastly expanded our ability to examine the interior and function of the GI tract at will, making potential in vivo evaluation much more extensive. Utilization of sacs, loops, rings, and cells have provided ample data to reveal the importance of the gastrointestinal tract as a barrier and absorptive organ and also as a highly active major metabolic tissue. Examination of the development of intestinal enzymes and metabolic pathways reveals an understanding of nutrient active transport and metabolism as well as metabolism of foreign substances. The relatively large mass of this organ system provides additional significance to its metabolic roles in the homeostasis of the organism as a whole.

Since ingestion is a major route of exposure to foreign substances, continued research involving the absorption and metabolism of these substances is needed. Currently, more Americans, Europeans, and Chinese are affected by serious diseases of the gastrointestinal tract than any other system except the cardiovascular system, which provides emphasis for the increasing concern for understanding the possible environmental contributions to gastrointestinal disease.

STRUCTURE

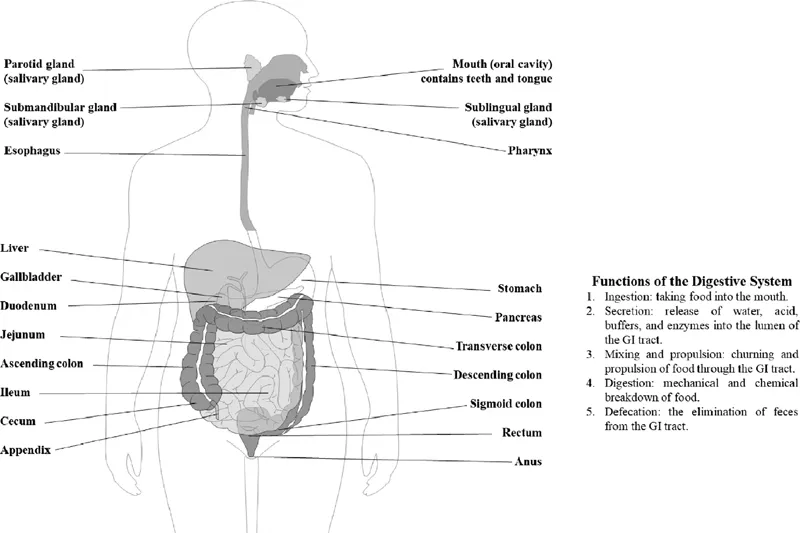

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract, or alimentary canal (shown in Figure 1.1), is a continuous tube that extends from the mouth to the anus through the ventral body cavity. Organs of the gastrointestinal tract include the mouth, most of the pharynx, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and large intestine. The length of the GI tract taken from an adult cadaver is about 9 m (30 ft). In a living person, it is much shorter because the muscles along the walls of GI tract organs are in a state of tonus (sustained contraction) (Guyton and Hall, 2011; Kumer et al., 2014; Sodeman and Sodeman, 1974; Tortura and Grabowski, 2003). It should be noted that the associated digestive organs are the teeth, tongue, salivary glands, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas.

The GI tract contains and processes food from the time it is eaten until it is digested and absorbed or eliminated. In portions of the GI tract, muscular contractions in the wall physically break down the food by repetitive mixing. The contractions for mixing also help to dissolve foods by mixing them with fluids secreted into the tract. Enzymes secreted by accessory structures and cells that line the tract break down the food chemically. Wavelike contractions of the smooth muscle in the wall of the GI tract propel the food along the tract, from the esophagus to the anus.

Figure 1.1 Right lateral view of head and neck and anterior view of trunk.

Overall, the digestive system performs six basic processes:

1. Ingestion. This process involves taking foods and liquids into the mouth (eating).

2. Secretion. Each day, cells within the walls of the tract and accessory digestive organs secrete a total of about 7 L of water, acid, buffers, and enzymes into the lumen of the tract.

3. Mixing and propulsion. Alternating contraction and relaxation of smooth muscle in the walls of the GI tract mix food and secretions and propel them toward the anus. This capability of the GI tract to mix and move material along its length is termed motility.

4. Digestion. Mechanical and chemical processes break down ingested food into small molecules. In mechanical digestion the teeth cut and grind food before it is swallowed, and then smooth muscles of the stomach and small intestine churn the food. As a result, food molecules become dissolved and thoroughly mixed with digestive enzymes. In chemical digestion the large carbohydrate, lipid, protein, and nucleic acid molecules in food are split into smaller molecules by hydrolysis. Digestive enzymes produced by the salivary glands, tongue, stomach, pancreas, and small intestine catalyze these catabolic reactions. A few substances in food can be absorbed without chemical digestion. These include amino acids, cholesterol, glucose, vitamins, minerals, and water.

5. Absorption. The entrance of ingested and secreted fluid, ions, and the small molecules that are products of digestion into the epithelial cells lining the lumen of the GI tract is called absorption. The absorbed substances pass into blood or lymph and circulate to cells throughout the body.

6. Defecation. Wastes, indigestible substances, bacteria, cells sloughed from the lining of the GI tract, and digested material that were not absorbed leave the body through the anus is a process called defecation. The eliminated material is termed feces.

Organs of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract are the mouth, pharynx, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and large intestine. Accessory digestive organs are the teeth, tongue, salivary glands, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas.

The wall of the GI tract from the lower esophagus to the anal canal has the same basic, four-layered arrangement of tissues. The four layers of the tract, from deep to superficial, are the mucosa, submucosa, muscularis, and serosa.

Mucosa

The mucosa, or inner lining of the tract, is a mucous membrane (as are the other surfaces of externally communicating body channels or orifices). It is composed of a layer of epithelium in direct contact with the contents of the tract, connective tissue, and a thin layer of smooth muscle (Russ and Pawlina, 2015).

The epithelium in the mouth, pharynx, esophagus, and anal canal is mainly nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium that serves a protective function. Simple columnar epithelium, which functions in secretion and absorption, lines the stomach and intestines. Neighboring simple columnar epithelial cells are firmly sealed to each other by tight junctions that restrict leakage between the cells. The rate of renewal of GI tract epithelial cells is rapid (5 to 7 days.) Located among the absorptive epithelial cells are exocrine cells that secrete mucus and fluid into the lumen of the tract, and several types of endocrine cells, collectively called enteroendocrine cells, that secrete hormones into the bloodstream.

The lamina propria is areolar connective tissue containing many blood and lymphatic vessels, which are the routes by which nutrients absorbed into the tract reach the other tissues of the body. This layer supports the epithelium and binds it to the muscularis mucosae. The lamina propria also contains the majority of the cells of the mucosa-associated lymphatic tissue (MALT). These prominent lymphatic nodules contain immune system cells that protect against disease. MALT is present all along the GI tract, especially in the tonsils, small intestine appendix, and large intestine, and it contains about as many immune cells as are present in all the rest of the body. The lymphocytes and macrophages in MALT mount immune responses against microbes, such as bacteria, that may penetrate the epithelium. It should be noted that current ICH and FDA guidance suggests examination of the MALT tissues when evaluating potential immunotoxicity (Gad, 2015).

A thin layer of smooth muscle fibers called the muscularis mucosae throws the mucous membrane of the stomach and small intestine into many small folds, which increase the surface area for digestion and absorption. Movements of the muscularis mucosae ensure that all absorptive cells are fully exposed to the contents of the gastrointestinal tract.

Submucosa

The submucosa consists of areolar connective tissue that binds the mucosa to the muscularis. It contains many blood and lymphatic vessels that receive absorbed food molecules. Also located in the submucosa is the submucosal plexus or plexus of Meissner, an extensive network of neurons. The neurons are part of the enteric nervous system (ENS), the “brain of the gut.” The ENS consists of about 100 million neurons in two plexuses that extend the entire length of the tract. The submucosal plexus contains sensory and motor enteric neurons, plus parasympathetic and sympathetic postganglionic neurons that innervate the mucosa and submucosa. Enteric nerves in the submucosa regulate movements of the mucosa and vasoconstriction of blood vessels. Because its neurons also innervate secretory cells of mucosal and submucosal glands, the ENS is important in controlling secretions by the GI tract. The submucosa may also contain glands and lymphatic tissue.

Muscularis

The muscularis of the mouth, pharynx, and superior and middle parts of the esophagus contains skeletal muscle that produces voluntary swallowing. Skeletal muscle also forms the external anal sphincter, which permits voluntary control of defecation. Throughout the rest of the tract, the muscularis consists of smooth muscle that is generally found in two sheets: an inner sheet of circular fibers and an outer sheet of longitudinal fibers. Involuntary contractions of the smooth muscle help break down food physically, mix it with digestive secretions, and propel it along the tract. Between the layers of the muscularis is a second plexus of the enteric nervous system—the myenteric plexus or plexus of Auerbach. The myenteric plexus contains enteric neurons, parasympathetic ganglia, parasympathetic postganglionic neurons, and sympathetic postganglionic neurons that innervate the muscularis. This plexus mostly controls tract motility, in particular the frequency and strength of contraction of the muscularis.

Serosa

The serosa is the superficial layer of those portions of the GI tract that are suspended in the abdominopelvic cavity. It is a serous membrane composed of areolar connective tissue and simple squamous epithelium. As we will see shortly, the esophagus, which passes through the mediastinum, has a superficial layer called the adventitia composed of areolar connective tissue. Inferior to the diaphragm, the serosa is also called the visceral peritoneum; it forms a portion of the peritoneum, which we examine in detail next.

The perit...