![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction: The teaching landscape

Introduction

What is it that helps someone to become an excellent teacher? What enables you to take your teaching to a new level? Essentially, what are the influences, approaches and actions that you need to consider or adopt in order to help you to develop your teaching? The aim in this book is not to present an end point or an ideal vision to which you might aspire but to explore a number of questions and to consider a range of responses, in order to stimulate your thinking about what might work for you in your professional context. We will explore the process of developing your teaching with the help of a number of colleagues, from a range of discipline backgrounds and from across the sector, through their case studies and personal reflections; and in one example through an extended think-piece on the concept of excellence in teaching. These approaches will help you to examine your practice though a number of lenses and support you to begin – and hopefully encourage you to continue – a process of self-evaluation on your practice; viewing it always as a ‘work in progress’ rather than the finished article. In a nutshell, this book is for everyone who would like to think more deeply about their teaching, for those who would like to enhance their practice, and to enable all of us to continue to develop as professionals.

We all need to be inspired, enthused and motivated to develop our practice. So, before we begin to look at what this book can offer you, take a few minutes to think about what you can offer yourself. Think about the following question and consider what your response tells you about your identity as a teacher in higher education and your approach to developing your practice.

My attitude to developing my teaching has been to:

- (a) do enough to get by

- (b) look for inspiration from others

- (c) attend staff development workshops

- (d) seek excellence

Do you grasp every development opportunity with both hands or do you wait to be prompted by others to engage with the idea of improving your practice? Are you the kind of person who wants to continue to grow and develop as a person and as a professional or are you happy feeling that you are doing ‘just enough’? Are you content to be this kind of person? This kind of professional? By choosing to read this book do you want make a change to your approach?

In a time where constant change has become the new normal this may sound worthy – but exhausting. The tertiary education system is also an area where adopting a positive and thoughtful approach towards your teaching may be viewed as an ambiguous career move in a climate apparently ruled both politically and economically by the demands of the research assessment exercise and the pressures to publish; and to keep on publishing. We need to be able to find the motivation to help us to maintain our currency and to retain our enthusiasm as learners ourselves. Maureen Andrade, from Utah Valley University, shares with us some insights into how she has achieved this.

The development of my teaching has been motivated by autonomy, mastery, and purpose (Pink, 2009). I thrive on autonomy to make decisions about what and how I teach. I seek mastery of my content and embrace opportunities to continue to learn through professional development, including my own scholarly contributions, and I am driven by purpose—helping learners fulfil their goals and sharing what I know with others. I have recently implemented the following new elements in my teaching:

- a team e-portfolio assignment in both an online and a face-to-face class

- feedback using a screencast video tool

- an online quiz game in class, where students participated using their smartphones, to help learners build foundational knowledge of concepts prior to application

- a website for class documents that students can access for in-class activities. A paperless environment!

I didn’t even dream of these activities 25 years ago. These approaches may not be new to others, but they were new to me. The answer to what helps one develop one’s teaching is partly motivation and partly the nature of teaching. Teaching involves the constant disruption of one’s practice.

Autonomy: not all of us have as much of this as we might like. On occasion we may be asked to teach someone else’s class and to have to use their material. Or we may find ourselves part of a team whose approach doesn’t quite gel with our own. And even if we do have some flexibility in what we do, we are often restricted by the teaching accommodation that we’re allocated as to where we are required to do it! Working at ways to create an element of autonomy is however, essential to us developing and being able to realise our own personal philosophy of teaching and to expand and enhance our practice.

In Chapter 2 we look at how we can go about exercising that autonomy by choosing effective approaches in our teaching. To what extent do we use our own personal experience as learners and how much do we base our practice on what we see around us, whether that’s colleagues in action, relevant literature or conferences? In Chapter 3 we look at the disciplinary influences that can play a significant role here and the ways of working that they involve. These ‘signature pedagogies’ can influence the acceptance or uptake of new approaches by our colleagues, while students may often not see the inherent benefit of some teaching and learning activities until later in their academic or professional career, if the activity takes them out of their comfort zone at that time. This can lead to pressures for us to think that there is one ‘right’ way to teach, in the same way that students can take a surface or strategic approach to their learning in looking for the ‘right’ answer as opposed to engaging with a reflective learning process.

And what is it that our students are telling us? In the current teaching landscape, the idea of the ‘student voice’ is a very powerful concept and it plays a central role in a student-centred approach to developing one’s teaching. Yet, whilst making for a good pedagogical approach, when coupled with the current focus on student fees and rising costs it can be distorted into a way of viewing students primarily as customers, rather than learners. Do students think this way too? Based on an online survey of over 1,000 full and part-time undergraduates in the UK (UUK, 2017) Universities UK reported that slightly less than half (47 per cent) of the undergraduate students surveyed saw themselves as customers of their university. While this is a significant figure the report also concluded that although ‘being a consumer is clearly an important part of being a student, it does not appear to be the overriding feature’ (UUK, 2017: 5). Positioning teachers and students in a consumer-based relationship has potential implications for how we teach and how our students learn. ‘When lecturers think of students as customers, it influences how they teach … Fear of bad teaching evaluations from students influences the extent to which lecturers challenge them’ (Matthews, 2018).

As we develop our teaching we also need to work at developing the kinds of relationships we have with our students, and the purpose they serve.

Universities that care about learning … value an educational culture in which the student-lecturer relationship is at the heart of teaching and learning. Staff at these universities tend to do more than talk at, about, or survey students, they talk with them.

(Matthews, 2018)

Across the teaching landscape, learning conversations are being re-framed and alternative narratives proposed. Chapter 4 looks at one of the most compelling of these narratives: students as partners. Working in partnership with our students in learning and teaching can be viewed as a robust response ‘to the all-too-common narrative of students as customers … and a chance for cultural change and a new way of “doing” higher education’ (Matthews, 2018).

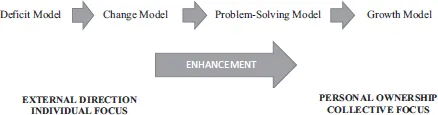

Lots of ideas then. However, when we begin to think about developing our practice there can appear to be many more questions than answers. Sometimes this is stimulating and motivating but it can also prove to be a turn off from development activities and you might feel that it is better to stick with tried and tested methods; if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. Yet, as professional university teachers we have ownership of and responsibility for our professional development. Eraut (1987) identified four models which reflect the history of approaches and attitudes towards teacher professional development (see Figure 1.1).

The four models trace the movement from an individually focused, externally directed approach to development towards greater personal ownership of the development process, and associated collective focus on practice and practical application of learning. Neither teaching nor development does – or should – take place in a vacuum!

Figure 1.1 Models of teacher professional development, adapted from Eraut (1987) The final stage, or growth model, facilitates ongoing professional development through processes such as inquiry and reflection. We explore the concepts of reflection and reflective practice in Chapter 5 where you are encouraged to look at your teaching using a range of tools, including lenses on practice, involving your colleagues, and developing your own strategies to incorporate reflection into your work as a day-to-day activity. In many ways, reflection can be considered as giving yourself feedback – and most importantly feedforward – on your practice, in the same way that you do for students on their work. It provides you with the opportunity to evaluate your current position and to use that information to plan for your future development. You can use a structured framework of questions to guide you through the process of self-evaluation, reflection and action planning. The structured nature of the questions supports you in addressing all aspects of the planning as the sequence of questions follows on logically one from the other, without allowing you to avoid any potentially difficult or challenging aspects! Table 1.1 provides an example of what such a framework might look like. You might want to consider including other questions that are relevant to your specific context.

The discipline of noticing

A good deal of richness and potential can come from learning derived directly from your teaching experience. Such emergent learning arises from your own practice in the course of your everyday activities, and is rooted in, drawn from, and based upon that experience. It comes from being more attuned to what Mason (2002) calls ‘the discipline of noticing’. Knowledge about your teaching develops, is tested, reviewed, and refined through iterative cycles that lead to the emergence of deeper understanding. We should not restrict ourselves to just our own ideas, however, and Chapter 6 moves on to discuss how you might draw ideas from working with others and taking a more collective approach to practice. Eraut’s (1994: 13) learning professional ‘relies on three main sources: publications in a variety of media; practical experience; and people’ (our emphasis). We invite you to engage with your colleagues in dialogue, debate and a more collaborative working approach to enhancing practice.

Table 1.1 Action planning reflective framework | What kind of teacher am I now? |

| What are my roles and responsibilities? |

| What does my personal philosophy of teaching look like? |

| What kind of teacher do I want to be? |

| Who are my role models? |

| What are my aspirations? |

| Where do I see myself in five years’ time? |

| How will I get there? |

| What are my short term goals? And long term? |

| What resources are available to support me? How can I access them? |

| What barriers exist to inhibit me from realising my goals? |

| How can I address these barriers? |

Much has changed in the higher education landscape since the first edition of Developing your Teaching was published. We now inhabit an academic environment that is fully digital, wholly global and undeniably comple...