![]()

Favorite Aunts and Uncles

Much contemporary queer culture uses lesbian and gay heros from the past to speak to our contemporary struggles with identity and community formation: Marshall recruits Hirschfeld, Yukhananov resurrects Fassbinder, Julien looks for Langston, Diamond outs Emily Carr, Bordowitz wants to fuck Ludlam, Tartaglia makes love to Genet, and Ottinger fearlessly invents an entire boatload of lesbian heroines. Such tributes to our perverse parents (both textually and cinematically) demonstrate how history can construct our present, but only if we construct our history.

![]()

The Third Body: Patterns in the Construction of the Subject in Gay Male Narrative Film

THOMAS WAUGH

Prelude: Victorian Gay Photography and Its Invisible Subject

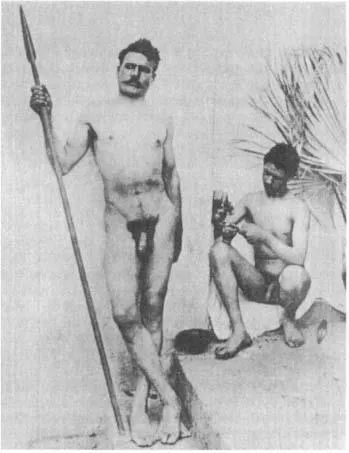

Nineteenth-century homerotic photography established a constellation of three types in its construction of the male body. The three bodies can be glimpsed through the photographs of Wilhelm von Gloeden, the Prussian aesthete and archetypal gay Victorian who worked in Taormina, Sicily until his death in 1931. Two objects of the homoerotic gaze, the ephebe and the “he-man” (the adolescent youth and the mature athlete, respectively) constituted polar figures in his work. The ephebe, Ganymede, was by far the most popular body type in the erotic repertory of the Victorian gay imaginary. He reflected both cultural justifications derived from the classical pastoral model, and economic and social realities of the period. The ephebe in drag was an important subcategory: cross-gender motifs offered not only an image of nineteenth-century sexological theories of the “Urning,” or the “third sex,” a biological in-between, but also a matter-of-fact acknowledgment of the marketplace scale of erotic tastes. The cross-dressed ephebe may also have functioned as an alibi for that homosexuality that dared not fully assume the dimensions of same-sex desire, a reassurance for the masculine-gendered body and identity of the discreet spectator (not to mention the producer and censor).

The ephebe was predominant in von Gloeden, and there were only occasional appearances of the “he-man,” the Hercules who substitutes maturity for pubescence, squareness for roundness, stiff, active untouchability for soft, passive accessibility. Apparently not von Gloeden’s cup of tea, the he-man was nevertheless very popular with other Victorian photographers, and omnipresent in other cultural spheres, from the Academy to the popular press and postcard industry, that is, in media that were on the surface more respectably homosocial than homosexual.

These two bodies together predicated in turn a third body, an implied gay subject, the invisible desiring body of the producer-spectator—behind the camera, in front of the photograph, but rarely visualized within the frame. The third body, the looking, representing subject, stood in for the authorial self as well as for the assumed gay spectator.

The Victorian homoerotic pattern of visualized objects and invisible subjects replicated those structures of Otherness and sexual difference inherent in all patriarchal Western culture. In fact, in gay culture, as we shall see, those structures seemed even exaggerated, as if to offset the sameness of the same-sex sexual relation, to unbalance the tedious symmetry of the Narcissus image. The ephebe addressed the phallic spectator as older, stronger, more powerful, active, just as surely as the female photographic object addressed its gender opposite, the heterosexual male spectator. At the same time, the he-man object addressed the more “feminized,” passive body of the homoerotic spectator. As for all the other variables entering Victorian gay iconography, from implied distinctions of class, age, and gender role to Orientalist and classical trappings, these clearly accentuated and elaborated on the basic built-in structures of difference.

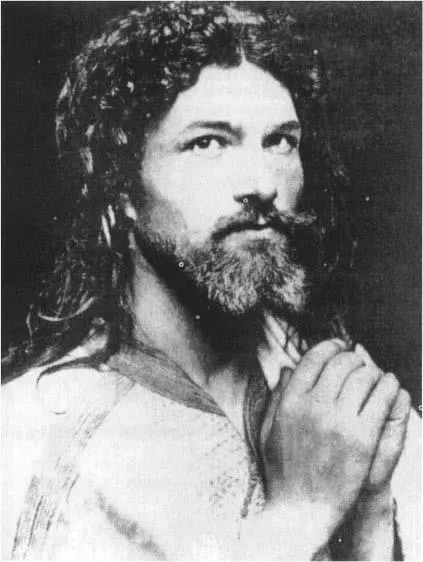

In Victorian gay photography the third body, the gay subject, became visible only in the minor genre of the self-portrait. Von Gloeden and his American contemporary Holland Day, both adopting the drag of Christ, anticipated the element of costume and disguise in the gay self-portrait in its later photographic manifestations of our century (think of George Platt Lynes and Robert Mapplethorpe).

Twentieth-Century Gay Cinema and Its Visible Subject

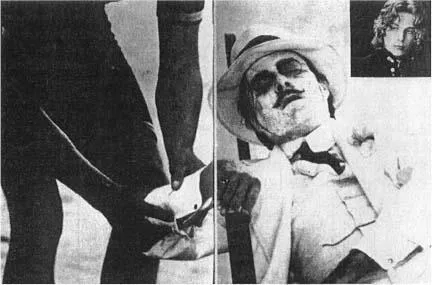

In the twentieth century, it is gay male filmmakers, competing with photographers as prophets of the homosexual body, who most definitely take up the job of constructing the gay subject. In the gay-authored narrative cinema, as gay themes become more and more explicit after the Second World War, filmmakers replace the alibis of their photographer precursors with an agenda of self-representation and self-definition. At the same time, they unfreeze the iconicity of the photographic body with the identificatory drive of narration and characterization. From his obscure corner in the photographic corpus, the third body finally enters the foreground of the image, alongside the ephebe and the he-man, the objects of his desire. In the new configuration of character types, the cinema provides two points of entry for the gay spectator: a site for identification with the narrative subject, and a site for specular erotic pleasure in his object.

Within a gay narrative universe that remains remarkably constant across the seventy-five-year span of my cinematic corpus, 1916–1990, the gay subject consistently accomplishes twin functions. On the one hand, he enacts a relationship of desire—constituted through the specular dynamics basic to the classical narrative cinema, the diegetic and the extra-diegetic gaze—and on the other, he enacts certain narrative functions that are more specific to the gay imaginary. These functions often have a literally discursive operation within the diegetic world. To be specific, the gay subject takes on one of, or a combination of, several recurring social roles, namely those of the artist, the intellectual, and/or the teacher. In other words, to complete the mythological triangle, Ganymede and Hercules are figured alongside, and are imagined, represented, and desired by, a third body type that is a hybrid of oracle, centaur, mentor … and satyr.

The gay subject looks at and desires the object within the narrative. As artist-intellectual he also bespeaks him, constructs him, projects him, fantasizes him, in short, represents him. He fucks with him rarely, alas, seldom consummating his desire as he would within the master narrative of the (hetero) patriarchal cinema built on the conjugal drive. The dualities set up by both photographers and filmmakers—mind and body, voice and image, subject and object, self and other, site for identification and site for pleasure—these dualities remain literally separate. For the most part, narrative denouements, far from celebrating union, posit separation, loss, displacement, sometimes death, and, at the very most, open-endedness. Yet, at the same time, the denouement may also involve an element of identity transformation or affirmation. In fact the assertion of identity, the emergence from the closet (to use a post-Stonewall concept), is often a basic dynamic of the plot, usually paired with an acceptance of the above separation, and signalled by telling alterations in the costumes that we shall come to in a moment. Through all of these patterns, the same-sex imaginary preserves and even heightens the structures of sexual difference inherent in Western (hetero) patriarchal culture but usually stops short of those structures’ customary dissolution in narrative closure. In other words, the protagonists of this alternative gay rendering of the conjugal drive, unlike their hetero counterparts, seldom end up coming together. We don’t establish families—we just wander off looking horny, solitary, sad, or dead. Or, as I said with denunciatory fervor along with everyone else in the seventies, gay closures are seldom happy endings. (Waugh, 1977)

Costumes

The physicality of the gay subject is cloaked, like Grandfather von Gloeden, in various corporal, vestimentary, and narrative costumes, which are in sharp contrast to the sensuous idealized bareness of his object, whether the he-man’s squareness or the ephebe’s androgynous curves. The third body puts on costumes as readily as the objects of his desire take them off. The element of costume has several resonances. Firstly it is obviously a disguise, a basic term of homosexuals’ survival as an invisible, stigmatized minority. Secondly, it operates to desexualize the subject within an erotophobic regime in which nudity articulates sexual desirability. Finally, costume is a cultural construction, which sets up the nudity of the object as some kind of idealized natural state, but at the same time acknowledges the historical contingency and discursive provenance of sociosexual identity, practice, and fantasy.

The costumes of the gay subject are familiar markers from the repertory of cinematic realism, drawing singly or in combination from a roster of attributes, each attribute predicating its opposite in the narrative object of desire. Thus we have:

A) age as opposed to the greater youth of the object (e.g. Mikael or Montreal Main);

B) class privilege as opposed to peasant, proletarian or lumpen affinities (e.g. Ludwig or Ernesto);

C) cultural-racial privilege as opposed to identities that are less white, or less European (e.g. Arabian Nights, Prick Up Your Ears, and Mala Noche);

D) clothing connoting all of the above, as opposed to nudity (e.g. A Bigger Splash or Flesh);

E) bodily condition, by which I mean markers such as eyeglasses, makeup, obesity, disease, and mortality, as opposed to beauty, strength, and health (e.g. Death in Venice, Caravaggio);

F) gender role as opposed to its complement (this pair is a reversible term: if the subject is feminized, the object is often masculinized, and vice versa, with narrative oppositions of active-passive or powerful-submissive assigned either in the traditional gender configuration (e.g. Flesh, The Naked Civil Servant); or

G) its inverse, that is, with the object exerting control over the subject (e.g. Querelle, Sebastiane).

Shifting Ground

All of these narrative functions and layers of narrative costumes constitute a mosaic of the gay self, the third body, which subtends the corpus of the gay-authored narrative cinema from the First World War to the present. Certain films stand out as prototypes of successive generations of the gay imaginary. Under the shadow of the German civil rights campaign of the Scientific Humanitarian Committee (1897–1933), the pair of films based on the gay novel Mikael, by Mauritz Stiller (1916) and Carl Dreyer (1924) respectively, together with the German social-reform narrative feature Anders als die Anderen (1919), produce the jilted artist and the violinist blackmail victim as the first gay subjects of the cinema.

In the considerably more repressed period after the Second World War, the works of Anger, Fontaine, and Warhol elaborate obliquely on the pattern. They tease out heightened and ambiguous tensions with spectator voyeurism and construct a gay subject that is partly obscured, displaced, or off-screen. In the early seventies, Visconti’s Death in Venice and Pasolini’s “Trilogy of Life” converge as a final celebration of a departed (fantasized?) sexual regime, as if to deny the rumblings of Stonewall (not to mention the women’s movement) on the other side of the Atlantic. Their younger contemporaries, like Larkin, Hazan, Peck, Fassbinder (Germany in Autumn), and Benner situate the gay subject within a complex, curiously antiseptic universe where visions of post-Stonewall affirmation are often achieved at a cost. Interestingly, in all of these latter films, the gay subjects’ strong nonsexual relationships with women rival the inter-male subject-object sexuality for dramatic space.

Finally, the flood of 1980s updates—the British pair Caravaggio and Looking for Langston dispelling the shadow of Section 28, the Canadian Urinal, the Dutch A Strange Love Affair, the Spanish Law of Desire, the numerous American entries from Abuse to Torch Song Trilogy—are all eclectic, postmodern renditions of the traditional configuration of the gay artist-intellectual, situated on various strata of the cultural hierarchy and in different relations to gay subcultural constituencies. These entries of the last prolific decade all reflect (implicitly or explicitly) shifting sensibilities and cultural-political strategies in the face of the antigay backlash and the Pandemic. Significantly, all reclaim the sensuous Pasolinian eroticism which the Stonewall pioneers had somehow downplayed.

As for the object types, Victorian iconography has undergone a radical shift as twentieth-century gay male culture has evolved. The predominant icon of the modern gay erotic imaginary, the he-man (in his postwar ghetto incarnations as “trade,” “clone,” and bodybuilder) has gradually supplanted the ephebe, in both his straight and “in-betweenist” shapes. Aside from some important exceptions, the ephebe is now relegated to stigmatized specialty tastes within gay culture. When young Thomas Mann imagined an ephebe at the center of his novella Death in Venice in 1911, he was in stride with his generation, but when old Luchino Visconti translated that vision literal...