- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The revised, updated version of this book includes an analysis of the sweeping political changes in South Africa since its original publcation in 1992. Other new material covers more theoretical issues and contemporary developments in scholarship, including a reconsideration of the film ?The Gods Must Be Crazy?; a discussion of ?expos thnography? and its attendant political/moral positioning; and an examination of the political situation in Namibia, with a close study of the near collapse of the Nyae Nyae Development Foundation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Bushman Myth by Robert Gordon,Stuart Sholto-Douglas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & African Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Bushmen: A Merger of Fantasy and Nightmare

Ethnology [is] at once the child of colonialism and the proof of its death throes: a dialogue in which no one has the last word, in which neither voice is reduced to the status of a simple object, and in which we gain advantage from our externality to the other.

—Todorov

Some films can kill. One such film was the blockbuster The Gods Must Be Crazy,1 which played to packed houses in the United States, South Africa and elsewhere. This film, with its pseudoscientific narrator describing Bushmen as living in a state of primitive affluence, without the worries of paying taxes, crime, police and other hassles of urban alienation, has had a disastrous impact on those people whom we label "Bushmen."2

The film unleashed a veritable vortex of television and him crews on what is officially known as "Bushmanland." In 1982 alone more than nine film crews visited Tsumkwe, including an eleven-member Japanese team and the famous Sir Laurens van der Post, bringing to realization, in an unanticipated form, a prophecy made in 1929 by the traveler Makin: "Perhaps someday, the Bushman will degenerate into that final humiliation—an exhibit by a travelling showman" (Makin 1929:275).

The success of The Gods Must Be Crazy gave a major boost to the Namibian Department of Nature Conservation's proposal to develop Bushmanland as a game reserve. In the world envisioned by Nature Conservation, Bushmen would be allowed to remain, provided that they "hunted and gathered traditionally." Of course most tourists would come not to see wild animals but to see "wild Bushmen."

In the same period the South African Defence Force (SADF), which had been fighting a low-intensity guerrilla war with the South West Africa People's Organization (SWAPO) since the early 1960s, made a concerted effort to recruit Bushmen. Indeed by the early 1980s Bushmen held the unique distinction of being perhaps the most militarized ethnic group in the world.3 One of the major reasons for military recruitment was the belief that Bushmen were "natural" trackers and thus would be effective counterinsurgency operatives. The SADF also exploited them culturally. The SADF was so proud of what it had done for (and to) these "last representatives of the stone-age" that, as a matter of course, visiting foreign journalists were shown the Bushman base at Omega.4 These journalists recorded a rich fund of characteristics that the white soldiers attributed to Bushmen. According to one senior officer, "The Bushman's senses in the field are unbelievable. If a patrol has a Bushman with it, then it is unnecessary to post guards at night. The Bushman also goes to sleep, but when the enemy is still far away he wakes up and raises the alarm" (Die Burger, 6 January 1982). Another white soldier believed: "They have fantastic eyesight and they can navigate in the bush without a compass or map. . . . With the Bushmen along, our chances of dying are very slight. They have incredible tenacity, patience and endurance. They've taught me to respect another race" (Time, 2 March 1981). Even experienced, battle-hardened mercenaries were impressed. A Soldier of Fortune article exulted:

Able to survive long periods on minimal food and water, the Bushman has an instinctive, highly developed sense of danger, and has proved to be an astoundingly good "snap" shot. . . [but his] forte is tracking. . . . If you've never seen a two-legged bloodhound at work, come to South West Africa and watch the Bushman. Actually, the Bushman puts the bloodhound to shame. [In addition, Bushmen are] good at estimating mortar projectile strike distances because of their age-old weapon—the bow and arrow.

(Norval 1984:74)5

According to that view, the superhuman qualities of Bushmen were grounded not in humanity but in animality. Their inability to herd cattle was attributed to their lack of self-restraint. As they are "extremely emotional," their women cannot be deprived of the men, and this determines the length of patrol (Pretoria News, 26 February 1981). Time magazine assured us that they are often distracted from a guerrilla track by honey, and when they sight a hyena, they laugh uncontrollably (2 March 1981).6 The transmogrification of Bushmen is still very much an issue.

The wave on which both the South African Defence Force and The Gods Must Be Crazy rode to acclaim both in South Africa and in the United States was clearly part of a larger current in contemporary scholarly discourse. This is the idea that Bushmen have always lived in the splendidly bracing isolation of the Kalahari Desert, where, in uncontaminated purity, they live in a state of "primitive affluence" as one of the last living representatives of how our paleolithic forebears lived. Indeed, the Bushmen, more than any other human grouping in the annals of academic endeavor, have been made a scientific commodity. Their continually rediscovered stature in the eyes of scholars has been exploited not only by academics but also by diverse groups, ranging from the South African Defence Force and the Department of Nature Conservation to ordinary Namibian schoolchildren, who all subscribe to the myth of primitive affluence and its various intellectual contours. Have the Bushmen become prisoners of the reputation we have given them?7

Despite the fact that most recent work in the Kalahari has stressed history and the wider context, almost all contemporary anthropology textbooks still portray Bushmen as if they live in a state of "primitive affluence." There is no simple answer to that question. In order to begin we must look at the history of research. Nancy Howell, one of the most prominent members of the Harvard Kalahari Project, recalled that the research project of which she was a member ignored the paraphernalia of Western "civilization and poverty"

because we didn't come all the way around the world to see them. We could have stayed at home and seen people behaving as rural proletariat, while nowhere but the Kalahari and a few other remote locations allow a glimpse of the "hunting and gathering way of life." So we focus upon bush camps, upon hunting, upon old fashioned customs, and although we remind each other once in a while not to be romantic, we consciously and unconsciously neglect and avoid the!Kung who don't conform to our expectations.

(Howell 1986)

The Bushman issue raised troubling questions for me, both as a Namibian and as an anthropologist. The dissonance between scholarly textbook rhetoric and actuality was forcefully brought home to me in 1980 when John Marshall, an ethnographic filmmaker, invited me to accompany him to Tsumkwe, the "capital" of the Apartheid-inspired Bushman homeland. What I saw there on my brief three-day visit was profoundly disturbing. I had never been in a place where one could literally smell death and decay, as in Tsumkwe. Indeed the death rate exceeded the birthrate. It was a prime example of what Robert Chambers called integrated rural poverty: The Tsumkwe people were caught within the mutually reinforcing coils of isolation, poverty, physical weakness, vulnerability and powerlessness (Chambers 1984:103).

When I grew up in southern Namibia, stories of the treacherous "wild Bushmen" and how they had to be "tamed" by tying them to windmills and force-feeding them mielie-meal were common coin. One of my most vivid childhood memories was looking at a picture in the Luderitzbucht Museum that showed Bushmen being hung from a camel-thorn tree. Was I dreaming? Or are we dreaming now? How to reconcile or indeed evaluate these discordant images of those labeled "Bushmen" is the guiding motif of this book.

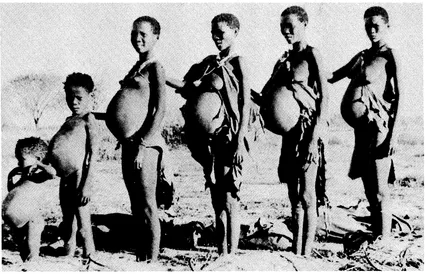

Bushmen: pregnant women and malnourished children. This photograph, taken in the 1930s, has appeared in books and newspapers with misleading captions, such as: "Bushmen after a raw meat feast"; "They have filled themselves with locusts, exactly as did their ancestors, the 'wild Bosjes'"Bushmen after a feast." Source: Windhoek Observer, July 24, 1982. (Photo courtesy of Windhoek Observer)

The Politics of Labeling Bushmen

The images that I have sketched were not, of course, invented or dropped ready-made from heaven. They are instead the products of discernable sociocultural factors that are firmly located in a history. This book analyzes the interplay among that imagery, policy and history. The indigenous people at the center of this book do not see themselves as a single integrated unit, nor do they call themselves by a single name; it follows thus that the notion and image of the "Bushmen" must be a European or settler concept. The focus is thus not so much on the Bushmen/Kung/Ju-/wasi/San or whatever one might like to call them but on the colonizer's image of them and the consequences of that image for people assumed to be Bushmen.

Social identity becomes meaningful only in relation to others; thus, in order to understand the image of the Bushman, we must consider that image as the product of interactions between those encompassed by the label and their "significant" others. "Only by understanding these names as bundles of relationships and by placing them back in the field from which they are abstracted, can we hope to avoid misleading inference and increase our share of understanding" (Wolf 1982:1). Because the Other cannot exist without the Self, this is a study not only of history but also of the sociology of knowledge.

One of the many issues academics have argued about concerns the label they impose upon these people. Some, like Guenther (1985), prefer the older term Bushmen. Others reject this term because they believe it is racist and sexist and prefer to use the term San (e.g., Lee 1979:29; Wilmsen 1989a:26-32; Wilmsen 1989b:31) on the grounds that San is derived from the term...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Illustrations

- Preface

- 1 The Bushmen: A Merger of Fantasy and Nightmare

- Part 1: What's in a Name?

- Part 2: The Colonial Presence

- Part 3: The Sacred Trust

- Part 4: Bushmen Iconified

- Part 5: Have We Met the Enemy and Is It Us?

- Appendix: Letter from Magistrate Gage, Grootfontein, to Gorges, Secretary of the Protectorate; Petition from Farmers of Nurugas

- Notes

- References and Bibliography

- About the Book and Authors

- Index