![]()

1

Fulbeness, History, and Cultural Pluralism

Rosaline

A few weeks after my arrival in the village of Domaayo, I was befriended by a fourteen year old Mundang girl named Rosaline. She was bright, strong-willed, and ambitious. Her father had been a Lutheran catechist and a strong believer in the value of Western education. She and her father lived across the river in a small settlement, a cluster of family compounds, near Domaayo proper but not contained by it. She had acquired from her father a strong aversion to Muslim advances, both ideological and social. The latter had become more and more frequent of late, in the concrete form of marriage proposals, which she received from Fulbe men and tenaciously refused. For Rosaline, marriage to a Muslim meant submission to his will and conversion, two unappealing prospects for a defiant Christian girl.

She first approached me when she heard I was looking for a translator and language teacher. She spoke French well, and though I didn't want a Mundang assistant (I worried it would complicate my work in a Fulbe community), I looked forward to her visits and the possibility of communicating easily with another girl. My host family made fun of her obstinacy in her girlhood and paganism. Her refusal to marry was widely discussed in the village. She had strong feelings about my Fulbe friends too. Eventually, we grew apart, but not before I had spent many hours walking with her, picking mangoes from her family orchard, and keeping her company while she sold vegetables at the roadside market. One afternoon, as we walked together through the village, she pointed to a respected mallum and notable, a scholar and courtier/attendant of the chief, Mai Suudi: "Look! Do you see this man? He is Mundang. He makes himself out to be Fulbe, but he is 100-percent Mundang." She made it clear that she saw him as an impostor, or worse—a traitor.

Her revelation was shocking, but I could not doubt her words. She knew him, and she knew his family. Yet my view of the taken-for-granted character of Fulbe ethnicity in this community was irrevocably shattered. This Islamic scholar in elegant white robes, who often affected the Arab turban and served as a close adviser to the chief—was a Mundang who had converted to Fulbeness? Perhaps a native-born Fulbe person would have immediately found a flaw in what I perceived as his seamless performance of Fulbeness. Upon reflection, I came to admire the enthusiasm with which he had embraced his chosen destiny in Islam and Fulbeness. Rosaline, as was clear from her tone, certainly did not. Later, the same mallum himself told me the story of his conversion, and he explained his devotion to spiritual things and his transformation from Mundang to Fulbe. Listening to Mai Suudi, and discussing his story with others, I began to see that the process of ethnic identification and the performance of ethnicity were central issues in this "Fulbe" village. I will return to Mai Suudi and his personal journey of conversion and transformation after first situating the Fulbe spatially and temporally in West Africa.

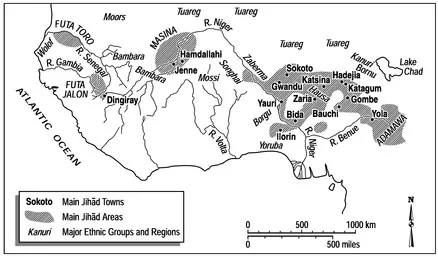

The Fulbe in West Africa

The Fulbe live in every West African country from Senegal to Nigeria and are found as far East as Chad, the Central African Republic, and the Sudan (Boutrais 1994; Riesman 1992). In every one of those states, they are a minority, but their total numbers (estimated between eight and ten million) make them one of the numerically most significant West African ethnic groups. Although the most well-known Fulbe people are nomads, less than half of contemporary Fulbe still raise cattle (Riesman 1992:11). The Fulbe are variously known as Fulani (in Anglophone Africa), Peul (in Francophone Africa), Woodaabe, Mbororo, Fula, Toucouleur, and Halpulaaren. They all speak varieties of Fulfulde, which are mutually comprehensible (between good-willed speakers). Their contemporary distribution in West Africa is due not only to their nomadism, but also to their military and religious activism and leadership. In Cameroon, Guinea, Burkina Faso, Niger and Nigeria, they headed religio-military jihads in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and established tributary states, some of which still stood at the time of European colonial expansion into the Sahelian zones (notably in northern Nigeria and Mali) in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Most of Domaayo's residents believe that their identity as Fulbe distinguishes them from their "pagan" neighbors known as haabe. Yet, when I asked villagers about their history, ancestry and origins, my questions were often met with puzzled shrugs, suppressed giggles, and embarrassed laughter. Usually the person I was talking to would refer me to someone else, who would in turn tell me to talk to some other "expert" about local history. No one, it seems, wanted to speak (or at least not in public) about their communal ancestry. Eventually, 1 learned that some of the ancestors of this community were Muslim men who had participated in Shekh Usumaanu's famous nineteenth century jihads, while other ancestors were non-Muslim farmers of non-Fulbe parentage (and therefore "pagan"). Some ancestors were nomadic pastoralists, while others were traders and Islamic clerics. The complexity of actual Fulbe ancestry appeared to contradict their claims to cultural superiority over their non-Fulbe neighbors. Privately, many men admitted that they are not "really Fulbe." However, in their relation to non-Muslim neighbors, they emphatically placed themselves in the Fulbe camp. Somehow, they were both proud of their collective claims to a distinctive Fulbe culture and heritage and worried that their personal claims to membership in that group might be undermined by too much probing.

Four Fulbe Jihads. Contemporary Fulbe settlements reflect the histories of pastoralism, migration, and jihads. Drawing by Clifford Duplechin. Adapted from David Robinson's The Holy War of Umar Tal. Oxford: Clarendon, 1985.

Domaayo

In many parts of West Africa, Fulbe identity is linked with cattle. Most Fulbe people in Domaayo, however, are farmers and traders. Domaayo residents grow millet, sorghum, peanuts, cotton, onions, garlic and some vegetables (such as cucumbers, melons, lettuce, and tomatoes) in irrigated gardens. In the rainy season gardens, okra, mallow, and other vegetables are grown. They will be dried and stored for use in sauces during the dry season, when fresh vegetables are hard to come by. Aside from cotton, the onions they sell are perhaps their greatest agricultural contribution to the Cameroonian economy. Only a few villagers owned cattle in significant numbers, and for most Fulbe people in Domaayo, cattle ownership was a nostalgic icon of their past wealth and glory. They enjoyed yogurt, butter and milk-based porridge (gaari) during the rainy season, but these items were usually purchased from the pastoral Fulbe who camped near Domaayo during their annual migration. Villagers admired the freedom and mobility of these "cow Fulbe" who seemed to have retained a greater degree of autonomy than they themselves had been able to since colonial times. For the sedentary Fulbe, many of the things which "make life sweet" must be purchased, and they are therefore constantly reminded of their entanglements in the monied economy and of their incomplete mastery of its operating forces.

The recent dramatic losses of political and economic power have created a tremendous feeling of uncertainty and alienation from state institutions among Fulbe people. The following section provides a brief overview of the Fulbe in West African history and in Cameroon. There follows an exploration of the often contradictory notions of Fulbeness, which coexist in the contemporary Fulbe community in which I did my field work. Identity in Domaayo is variously said to rest on ancestry, a "racial" notion of physical attributes, religion, or the performance of Fulbeness.

Fulbe History

In northern Cameroon, most of the contemporary Fulbe trace their arrival in the region to the 1804 jihad led by Shekh Usuman Dan Fodio of Sokoto, Nigeria, although an unknown number of Fulbe pastoralists, traders and sedentary Islamic scholars were already living in the region prior to the jihad (Schilder 1994:100). The holy war led to the establishment of the Sokoto Caliphate with an Emirate in Adamawa (now a province of northern Cameroon), which answered to Sokoto and in turn was answered to by a number of hierarchically arranged local chiefdoms. Many of the pre-existing local populations were made into tributary groups of the Fulbe rulers. And many local residents converted to Islam.

Concepts of ethnicity in northern Cameroon are characteristically based on a distinction between pagan and Muslim. As a rule, all Muslims are considered to be Fulbe, and all non-Muslims, of various heritages, are lumped into the category "pagan". The latter are frequently referred to as haabe (the Fulfulde word for pagan) or kirdi (the term for "pagan" used in the sweeping generalizations of French colonial administrators). Locally, the Mundang, Tupuri, Guiziga, and Guidar are the Fulbe's primary non-Muslim neighbors. Fulbe people I knew tended to look down on members of these ethnic groups as mere haabe, an attitude which has its roots in the Sokoto empire.

During the nineteenth century, the outright incorporation of Mundang individuals into the Fulbe population occurred through the Fulbe adoption of Mundang twins, who were considered dangerous to their parents, through slave raids, which often captured young children, and through the Mundang sale of children in times of famine (Schilder 1994:108). These children grew up in Fulbe communities, speaking Fulfulde and knowing only Fulbe culture, though they were always seen as haabe captives. Fulbe also participated in the West African slave trade, supplying slaves to Hausa traders, significantly enriching their economy. Paradoxically, the economic success of the Fulbe traders depended on the availability of potential slaves, which were, naturally, their pagan neighbors. The trade thus both thrived on the incomplete subjugation of the Mundang and fostered the persistence of a Fulbe/pagan distinction. Schilder (1994:118) argues that this may have dampened the missionary zeal of Fulbe, as Islam forbids slave raiding among Muslim populations. As long as haabe populations lived near the Muslim Fulbe, they engaged in dry season slave raids, which were justified as jihads, or holy wars.

Religious and Ethnic Conversion

With this history in mind, one gets a deeper appreciation of the power of ethnic categories in contemporary Cameroon. As Mai Suudi's case illustrates, ethnicity in Northern Cameroon has as much to do with residence and religion as ancestry. A person who is Mundang might move to a city as a young adult, convert to Islam, speak Fulfulde and dress in Islamic fashion—long flowing robes rather than western, tailored clothes. In this way, he can become Fulbe. He and his acquaintances will not forget that his ancestry is Mundang, but his chosen ethnicity will be Fulbe. Islam favors this process of ethnic conversion as teachers encourage the treatment of fellow Muslims as brothers, without discrimination as to ancestry. "Aren't we all children of Adam?" I often heard mallums ask rhetorically. Many residents of Domaayo were married across ethnic boundaries, if those were to be defined by ancestry. A man could easily marry a Mundang woman, I was told, as long as she converted to Islam. During the height of the nineteenth century slave trade, Fulbe men also married Kanuri, Shoa Arab, and Hausa speakers, all predominantly Muslim people who enjoyed free status (Fisher 1978:371). If a woman spoke Fulfulde well, and conformed to local ways of doing things, treating her neighbors as fictive kin, she would be accepted as easily as a native Fulbe woman. The emphasis of ethnic solidarity thus seems to be on the performance of ethnicity. Throughout West Africa, the Fulbe have successfully assimilated people of varied ancestry, strengthening their population demographically, as well as facilitating their political rule over diverse populations during periods of empire building (see Willis 1979). Conversion, inter-ethnic marriage and adoption were the principal vehicles for Fulbeization of peoples of varied ancestry in the region. The same views on the process of ethnic assimilation, which were applied to neighboring ethnic groups were also applied to the visiting anthropologist. Having shown interest in Fulbeness by struggling to learn the language, I was encouraged to take on more and more of the Fulbe repertoire and was praised for my efforts. As the Rosaline story illustrates, I was also disciplined when I "crossed over" and mixed with people of other ethnic groups.

My host family teased me about my friendship with her. Rosaline, too, taunted me by ridiculing my "so-called Fulbe" friends and neighbors. Although her claim that Mai Suudi was 100-percent Mandang shocked me, I was curious to hear what he would say about his own identity. Fortunately, Mai Suudi had heard about my inquiries into the ethnic origins of Domaayo residents, and he wanted to tell me his own version of things. Mai Suudi loves to talk, and I quote him below, to give the reader a chance to see how he thinks about himself and his world.

Mal Suudi's Transformation: The Fulbeizing of a Mundang

Mal Suudi spoke to me one afternoon about his Islamic studies, his identity, and ancestral origins. We had been chatting amiably on the side of the road, when my questions about his religion prompted him to give me his educational history in a speech which turned into an impassioned profession of faith:

I studied the Koran under Mai Nyaako for ten years. When I had read it completely, they sacrificed a large cow for me. They prayed the fatya (a prayer of thanks). I became a mallumjo then! So that others would know I had finished reading the Koran, they gave me a Koran. Amen. They gave me a book. I entered into my own saare then (that is, got married). For ten years, I had carried wood for him (Mai Nyaako, his teacher), gave it to him with my hat off (a submissive pose). The wood was (for light) to read the Koran and to make writing tablets (alluha).

The Arabic books (je deftere Arabia), I studied with Alhaji Bello. There were three books. There too I studied for six years after having finished the Koran. I read laadari, I read dawa I di salaati, I read tawhiidi, I read 'kurdeebi, I read halli mashiiru. These five books were written by Shehu Laadari (an influential Koranic scholar).

Then, I entered the party, I entered the world, I entered the ganjal—I danced the flutes—I entered sukaaku. But now, I have left all that be- hindi I am only praying, I am only doing the work of the religion. (Mi nasti haala parti, mi nasti dunyaaru, nastu mi ganjal—j'ai dansée les flutes—mi nasti sukaaku. Too, jonta kam, mi acci pat, mi don juula non, mi don wadda kmigal diina non.)

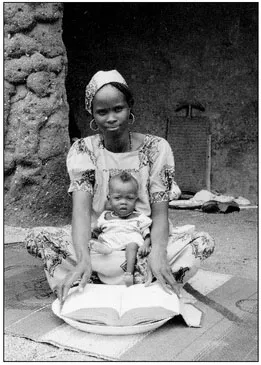

Posing with Koran and baby

Mal Suudi testifies to the labor and hardship involved in becoming learned in Islamic knowledge. Sixteen years of study and submission to the authority of the teacher have made him one who has read (jangi) and therefore, one who can act as a spiritual advisor, healer, and teacher. But he is no saint, he lets me know. He became involved in partying, in the concerns of this world and the world of women. The flutes (ganjal) refer to the alluring world of sukaaku in which young Fulbe men gambled their belongings to "win" a woman for one night.

Fulbe talk about the "temporary ma...