- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This case study examines emigrants from Namoluk Atoll in the Eastern caroline islands of Micronesia, in the Western pacific. Most members of the Namoluk Community (cbon Namoluk) do not currently live there. some 60 percent of them have moved to chuuk, Guam, Hawai'i, or the mainland United states (such as Eureka, California). The question is how (and why) those expatriates contine to think of themselves as cbon Namoluk, amd behave accodingly, despite being a far-flung network of people, with inevitable erosions of shared language and culture.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Namoluk Beyond The Reef by Mac Marshall in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Asian Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Openings

Looking for the suitable time, Pukueu

Went to observe the break of day at the other end of the island.

A steering wind blew, it blew from the east,

His canoe would be pulled out from its headrests:

Yet suddenly came his asipwar

To stop Pukueu’s voyage.

But he did not change his mind; his eager heart sought the satisfaction

To open up those dark seas.

Theophil Saret Reuney (I994 254)

OPENING DARK SEAS

We lingered under the coconut palms at Leor to say our good-byes and shake everyone’s hand before we left to return to Seattle. Quicker than we expected or wanted, it was time to leave Namoluk Atoll where Leslie and I had lived for the past two years. As we waded through the warm, crystal-clear water and clambered into the motorboat that would wend through the narrow reef channel to the open sea where the government ship waited, a few women began to keen as if we were dead. Others took up the cry, and as our boat moved away from shore, we were soon overcome by the emotion of a Pacific island parting. Sobbing along with us was our fourteen-year-old “daughter” Maiyumi, who was feeling the sweet sadness of departure from her home island for the very first time.

We had composed ourselves somewhat before coming alongside the Truk Islander, and strong arms reached down to help Leslie and Maiyumi up the ladder and onto the ship’s deck. After handing up our last bits of luggage, I followed them, and the three of us stood together at the railing as the ship moved slowly away. Small children ran along Namoluk’s shoreline, and Maiyumi’s mother, Sabrina, waved a palm frond back and forth in farewell. The ship gained speed, and before the island faded to a mere speck on the horizon, the flash of handheld mirrors sent the sun’s rays to us in a final silent good-bye.

As Namoluk disappeared, Maiyumi’s momentary sorrow was soon replaced by the anticipation of visiting our destination—the urban center in Chuuk, an overnight voyage away to the north. She had graduated from eighth grade on Namoluk a few months earlier, and we were about to finalize her enrollment in a Protestant-run high school that would begin classes later in the month. The captain decided to spend the night anchored in Losap’s protected lagoon, and the next morning after off-loading some seedling coconuts and selling a few remaining goods, we set sail for the mountainous volcanic islands of Chuuk Lagoon. The passage from Losap Atoll to Chuuk is not far, and the ship bypassed the captain’s own island, Ñama, en route, making the journey shorter than usual. To Maiyumi’s wonder, the tops of Chuuk’s higher peaks came into view even before we steamed past the outer reef to reach the northeast pass. Once the Truk Islander slipped through the pass, she no longer rolled with the dark open ocean swells, and the captain made straight for the dock area on Wééné Island. As we drew closer, we could see homes scattered along the shoreline road below the rounded octopus head of Mt. Tonaachaw and then the miscellany of stores and government buildings concentrated in the “downtown” area and up on the elevated saddle called Nantakku.

When government field-trip ships come in from outer islands like Namoluk, they tie up at the main pier to unload. On this day, however, the pier was already occupied by the Asterion, a large freighter from overseas, so the Truk Islander had to drop anchor, and everyone and everything had to be lightered ashore on a 60-foot-long military surplus landing craft. The three of us gathered our belongings and were soon propelled shoreward to be greeted by a host of Namoluk people who had come to meet the ship. After chatting awhile, and eager to clean up and wash off the salt spray from our voyage, I hailed a taxi to carry us to the campus of Mizpah High School. We would stay there—in small guest rooms up on the hillside under the massive old mango trees planted by New England Congregationalist missionaries in the nineteenth century—until Leslie and I returned to the United States in a couple of weeks and Maiyumi moved into her dorm room almost next door to begin ninth grade.

The taxi I found was typical: a small Datsun pickup truck outfitted with wooden benches along each side of the bed for people to cling to as it jounced along Wééné’s mostly unpaved roads at 5–10 mph. The driver helped me load our possessions into the back, and Leslie climbed up after them. Meanwhile Maiyumi just stood next to the truck, and Leslie urged her, “Come on, Maiyumi, get in!” She continued to stand there quietly, looking perplexed, and as I climbed up into the truck bed so she could ride comfortably in the cab, I said with a trace of irritation, “What’s wrong, Maiyumi? Let’s go!”

At that, she turned to us with a shy smile and asked, “How do I open it?”

OPENING A WIDER WORLD

Chon Namoluk, “the people or citizens of Namoluk Atoll,” have been learning how to open new things for more than a century as the colonial powers in Micronesia have shifted from Spain to Germany to Japan to the United States, and now to their participation in the independent country of the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM).1 Of course, like many other Pacific islanders, long before such external control was imposed, Namoluk people maintained contact with communities on numerous other islands via sailing canoe voyages using sophisticated celestial navigation techniques. Although such regular contacts introduced chon Namoluk to occasional new ideas and objects, for the most part the other Micronesians with whom they were in contact shared a common pool of information and materials.

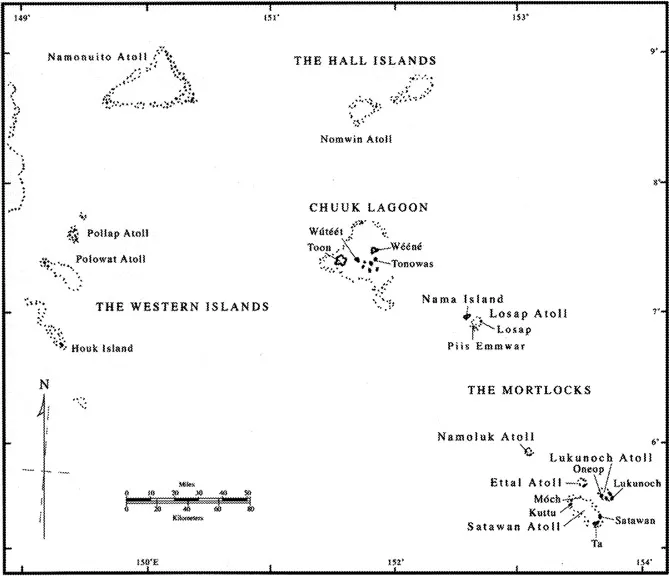

Travel beyond the sphere of traditional voyages and encounters away from the atoll with foreigners from industrialized societies did not begin for Namoluk people until the Germans recruited labor for the phosphate mines on Nauru and Angaur after 1906 (see Map 1.1). None of the Namoluk men who worked in these mines during the German colonial era before the outbreak of World War I was still alive when I first went to the atoll in 1969. Although they had “opened” the door to wage labor and learned to live among people who spoke languages other than their own, their experiences occurred within a familiar geographic setting. The number of Namoluk men engaged in such labor increased markedly during the Japanese colonial period, especially prior to World War II when the Japanese conscripted island laborers to work the phosphate mines on Angaur and Fais and to help construct airfields, bomb shelters, roads, and military installations. Also during the Japanese time, some Namoluk people gained access to a few years of elementary education. Young women as well as young men left their island for school on Oneop in the Mortlocks2 and (for some) on Tonowas in Chuuk Lagoon (see Map 1.2). A small number of chon Namoluk held paid jobs in the Japanese colony in Chuuk. More doors (and eyes) were opened by these experiences, but once again they were limited to familiar Micronesian locations.

Only well after World War II, with the advent of American colonialism in Micronesia, did Namoluk people begin to travel farther afield. On my first visit to the atoll in 1969, only four Namoluk persons resided outside of the U.S. Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (USTTPI, or the Trust Territory), a jurisdiction set

Map 1.1—Micronesia (Including the Caroline, Mariana, and Marshall Islands)

SOURCE: Modified from a map prepared for the Center for Pacific Island Studies at the University of Hawai’i at Manoa, 1997.

up by the United Nations at the end of World War II under control of the United States after it defeated Japan (the previous administrative power). These included a middle-aged woman living on Guam with her second American husband, a young woman attending her final year of high school on Guam, a young man doing the same as an exchange student in Oregon, and another young woman enrolled at Honolulu Community College. At that time, a mere thirty-four years ago, only one Namoluk person had earned a college degree. As we shall see, these circumstances have changed markedly over the past three decades. The chapters to follow illustrate some of the experiences chon Namoluk have had as they embraced new places of residence, work, and school.

Map 1.2—Chuuk State, Federated States of Micronesia

The remainder of this book focuses on migration from Namoluk and the openings it has provided for engagement with a wider world. Migration to Wééné beginning in the 1960s, movement to the United States from the early 1970s, the establishment of roots on Guam commencing in the late 1980s, and the buildup of a Namoluk network in Hawai’i over the last decade will receive attention, as will occasional migration to other more distant places.

OPENING THE FLOODGATES OF MIGRATION

From the dawn of history, human beings have moved around and migrated. Micronesians—especially the atoll dwellers with their sophisticated deep water sailing canoes and remarkably accurate star compass—not only migrated originally to their island homes via sea highways, but they also maintained a high degree of mobility through interisland voyages. Movement, migration, and voyaging beyond the horizon are nothing new to Micronesian people.

During the Japanese colonial period (1914–1945), active efforts were made to discourage and prevent interisland canoe voyages, although the numerous small ships that plied among the islands provided an alternative means of moving about. These efforts were not entirely successful—especially in the Western Islands of what is now Chuuk State and in the more remote atolls in Yap State, where the navigational arts continued to flourish (e.g., see Gladwin 1970)—but they did decrease the frequency of canoe voyaging and contributed to its demise on many islands such as Namoluk. When the United States replaced Japan as the colonial power in Micronesia following World War II, it continued the provision of small interisland “field-trip” ships to carry passengers and cargo back and forth between the urban centers and outer island communities. Overall, these interruptions to and reductions in direct voyaging among many of the islands, combined with the availability of field-trip ships, contributed to a center-and-periphery pattern of transportation and reduced the density of interisland networks. For example, in pre- and early colonial times Namoluk people sailed from their island to Polowat Atoll and back, without intermediate stops. By the post-World War II period, someone wishing to travel from Namoluk to Polowat had to catch a field-trip ship to Wééné, Chuuk, and then wait weeks or sometimes months until a different field-trip sailed for Polowat. Such shifts in transportation patterns served to strengthen the importance of the urban center.

Even so, the Trust Territory’s urban centers grew very slowly until the advent of the Kennedy administration and much larger island budgets in the 1960s led to an expansion of infrastructure and wage employment. In Chuuk, this growth of the town center initially had only a modest impact on most outer island communities such as Namoluk, although it stimulated some limited population movement from the atolls to town in search of short-term employment. Such communities as Namoluk, then, remained largely “intact” through the mid-to-late 1960s, in the sense that the great majority of their members continued to reside “at home.” The first significant factor that pulled chon Namoluk to the urban center on Wééné was what Francis X. Hezel (1979) has called “the education explosion,” a phenomenon that he dates to 1965 and to Truk3 High School’s first graduating class.

With greater opportunities for a high school education from the late 1960s onward, the emigration of Namoluk’s people—especially its young people—began in earnest. These opportunities were furthered by the establishment of junior high schools (ninth and tenth grade) in 1970, with the one for the Mortlocks located on Satawan Islet, Satawan Atoll (see Map 1.2). The tremendous increase in the number of high school graduates in Chuuk from 1965 to 1977 that Hezel (1979) documented was joined by an expansion of scholarships and other funds to pursue a college education in the United States.

These resources provided the financial wherewithal for hundreds of Chuukese high school graduates to enroll in colleges and universities in Hawai’i and on the U.S. mainland, beginning in the early 1970s. Namoluk students were prominent among these college migrants, as will be discussed in subsequent chapters.

The next big stimulus to migration from places like Namoluk to Wééné and beyond resulted from a combination of factors. Many of the college students who went to the States in the 1970s returned and found salaried jobs, particularly government jobs, in Micronesia’s urban centers. Those who followed just a few years later, however, returned to find nearly all the available jobs taken, and they grew restive (Larson 1989 provides a sensitive account of their dilemma). Casting about for work, some of these young adults moved to Saipan during the early 1980s. Saipan, the capital of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI), had earlier been the capital of the USTTPI, and consequently people from elsewhere in Micronesia could freely immigrate there. The CNMI experienced a tourist boom during the 1980s as large numbers of high-end hotels were built by Japanese corporations to cater to a Japanese market. In addition to jobs in Saipan’s tourist industry, numerous Micronesians, including a few from Namoluk, found employment in the two dozen garment factories that were set up there beginning in 1983 to exploit cheap labor and to find a way around U.S. import quotas of clothing from foreign countries.

At about the same time that hotel construction and tourism took off on Saipan, it also began to boom on Guam, notably after early 1984 (see Map 1.1). By this time job prospects in places like Wééné were poor to nonexistent, but immigration of Micronesians to Guam was still tightly controlled. Then things changed. With the implementation of the Compact of Free Association between the newly constituted Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) and the United States on November 3, 1986, “For the first time Micronesians were allowed free entry into the US and its possessions to live and work without restriction” (Hezel and McGrath 1989, 49). Not long thereafter, the number of Micronesians who moved to Guam grew by leaps and bounds, and by September 1988 approximately 1,100 people from Chuuk State were living there (Hezel and McGrath 1989). Most of this migration was in search of jobs, although better schools and health care also figured into people’s decisions to move to Guam. At first only a few Namoluk people were part of this late-1980s flow, but within a very few years—by 1995—Guam had the third largest number of Namoluk people of any location (see especially Chapter 8).

In the late 1990s, Guam’s economy began to sour, and Micronesians resident there—along with others from their home islands—went to Hawai’i and the U.S. mainland in growing numbers. There they joined some of their compatriots who had gone originally to the United States for college in the 1970s and had never left. Most such “long-timers” had married Americans and had children, so they were allowed to stay in the country before the Compact was signed for that reason. During the past thirty years, a number of places in the United States have attracted especially large numbers of people from Chuuk State, for example, Honolulu; Portland-Salem, Oregon; and Corsicana, Texas, to name but three. These beachheads in a new Micronesian archipelago now contain three- or four-generation families, workers, students, and spouses of varied ethnicities. Once again, as we shall see, chon Namoluk have been fully participant in all of these developments. By midsummer 2001, more than a quarter of Namoluk’s population was resident in the United States or its territories, with 10 percent of them in the fifty states, and another almost 18 percent located on Guam. This book is a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Abbreviations and Acronyms

- Series Editor Preface

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- 1 Openings

- 2 Namoluk Atoll, 1969

- 3 Journeyings

- 4 Namoluk People, 2002

- 5 Heading Off to College

- 6 Heading Off to Collage

- 7 Reef Crossings

- 8 Four Locations Beyond the Reef

- 9 Closings: Points of Departure

- Glossary

- Suggestions for Further Reading

- References

- Index