- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In Unlikely Couples, Thomas E. Wartenberg directly challenges the view that narrative cinema inherently supports the dominant social interests by examining the way popular films about "unlikely couples" (a mismatched romantic union viewed as inappropriate due to its class, racial, or gender composition) explore, expose, and criticize societal attit

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Unlikely Couples by Thomas E. Wartenberg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medien & darstellende Kunst & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Subversive Potential of the Unlikely Couple Film

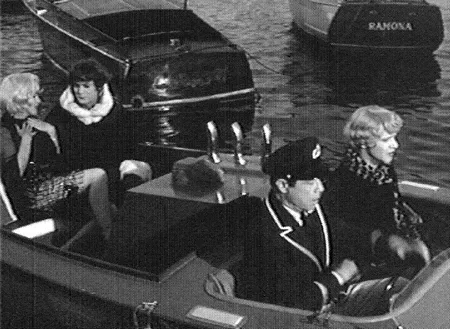

In the final sequence of Billy Wilder’s 1959 comedy, Some Like It Hot, two couples are seated in a motor launch (see Photo 1.1). The pair in the stern appears to be lesbian, the one in the bow heterosexual. According to the terms used in this book, the former couple seems unlikely, transgressive of the social norm specifying that romantic couples must be composed of a man and a woman, a norm to which, by contrast, the latter couple appears to conform.

Things are not that simple, however, for two of the three “women” in the launch are actually men in drag. The situation, then, is really the opposite of what it seems: The truly unlikely couple is the apparently heterosexual but actually homosexual one seated in the bow, whereas the genuinely likely couple is the apparently homosexual but actually heterosexual one seated astern. The image of these two contrasting couples, taken together with the inversion of their apparent and real natures, anticipates a number of important themes that will emerge in this study of a genre I call “the unlikely couple film.”

Let us look more carefully at the “lesbian” couple, composed of Sugar Cane (Marilyn Monroe), a nightclub singer, and Joe (Tony Curtis), a womanizing saxophone player who is disguised as Josephine: Apparently unlikely, the only really improbable element in this relationship is that Joe—a cad of the sort for whom the unfortunate Sugar has repeatedly fallen—has himself fallen for her. As a result, instead of pursuing his seduction, he now feels compelled to confess his love.

Photo 1.1 Two couples—one likely and one unlikely

The inversion of appearance and reality this seemingly unlikely pair embodies provides one key to understanding the structure of the unlikely couple film, for it is predicated on a conflict between two approaches to the featured couple. From one point of view, which I shall call the social perspective, an unlikely couple is inappropriate because its composition violates a social norm regulating romance. The image of Joe-in-drag with Sugar is as striking and delightful a visual representation of unlikeliness as the movies offer—and one that immediately registers the couple’s (apparently) transgressive character.

The contrasting point of view, which might be called the romantic perspective, and which is usually, but not always, that of the filmmaker, deems the transgressive couple appropriate—likely, I shall say—setting the love the two partners share above the conventions it violates. Because Joe loves Sugar, the audience understands that the two really do belong together, regardless of how they look. Of course, since this couple’s unlikeliness is the result of Joe’s dissembling, their unorthodox appearance does not signify a real obstacle to their relationship.

The situation is quite different in the ten films discussed in the chapters that follow, for all feature couples genuinely violative of the gender, class, racial, and/or sexual norms governing socially permitted romance. Hence, the conflict between romantic love and societal norm represented in the narrative figure of the unlikely couple cannot be resolved in these films, as it is with Sugar and Joe, with the simple revelation that its unlikeliness is merely apparent.1

Shifting our attention now to the pair seated in the bow of the launch, we see another couple whose appearance belies its reality. This apparently heterosexual, but actually homosexual, couple is composed of Osgood Fielding (Joe E. Brown), the eccentric millionaire at the helm, and Gerry (Jack Lemmon), who, to give his friend, Joe, time to seduce Sugar, has himself inflamed Fielding by masquerading as Daphne.2 When Daphne/Gerry admits to really being a man in hopes of cooling Osgood’s passion, Osgood does not respond with the outrage and disgust that Daphne/Gerry expects but deadpans one of the most famous tag lines in film, “Nobody’s perfect.”

Osgood’s response to Daphne/Gerry’s revelation elicits our startled laughter because it treats the sex of a romantic partner as just a minor matter—a “detail,” to quote The Crying Game, a film I discuss in Chapter 11—rather than the major problem we know it to be. But if, as it should, our laughter prompts us to reflect on why Osgood’s response is so startling, the subversion of heterosexuality’s normative status has been initiated.

The ending of Some Like It Hot thus gestures toward a crucial feature of the genre—transgressive romance as a vehicle for social critique. By focusing attention on the social norms governing romantic attachments, these films confront very basic questions about social hierarchy, for the norms reflect fundamental societal assumptions about the differential worth of human beings. The interpretations presented in this book emphasize how the very structure of the unlikely couple film entails this possibility: Since the narratives of such films must mediate the conflict between the romantic love that binds the unlikely partners and the social norms it violates, they can mobilize sympathy for the couple for purposes of critique.

My attribution of socially critical ambitions to popular narrative films like Some Like It Hot may strike readers as odd, for such films do not present themselves as vehicles for serious social analysis. Some Like It Hot can stand as a metaphor for my response to this challenge: Sugar, the stereotypical “dumb blonde” the womanizing Joe targets for seduction, invites easy condescension, but the more he comes to know her—as Josephine, he plays at being a sympathetic woman friend while actually acquiring the information necessary to bed her—the more difficult he finds it to reduce the totality of her being to her appealing surface.

Joe’s initial attitude toward Sugar resembles the perspective dominant in academic film studies: Too often, the “sexy” production values of narrative films, especially Hollywood films, are taken as a license for conde-scension.3 Although this attitude has not gone unchallenged, the reigning assumption has been that popular narrative films are necessarily complicit with dominant social interests.4 Since many of those who write about film see themselves as hostile to such interests, they have been correspondingly suspicious of box office success. Assuming a posture of superiority, these writers contemptuously dismiss such fare as superficial.

The stance adopted in this study is reminiscent instead of a chastened Joe’s at the end of Some Like It Hot: Just as he no longer reads Sugar’s attractions as evidence of her superficiality, I refuse the reflexive condescension that popular narrative film often evokes. To repeat, a central goal of this book is to demonstrate that unlikely couple films include important social criticism even as their audiences find them entertaining and appealing. To the extent that my interpretations succeed in showing that instances of the genre mount sophisticated challenges to hierarchy—whether of class, race, gender, or sexual orientation—they also illustrate how empathetic yet critical readings of these films reveal more about their structure and effects than the hypertheoretical dismissal so prevalent in the academic study of film.

Although I emphasize the socially critical, hence subversive, potential of the unlikely couple film, I recognize that not every, or even any, individual film fully and consistently realizes that potential. Works of art, like other cultural products, bear traces of the contradictions of their societies. A film that seeks to subvert the hold of one mode of social domination may inadvertently support that of another. Alternatively, a film that attacks, say, one stereotype may employ others, equally demeaning.5 Films do not live up to the ideal of consistency any more than do their human makers.

More problematic for my argument are those unlikely couple films with narratives that support dominant social interests. The act of criticism required by these films is complex, calling for an analysis of how they mute the genre’s critical potential. So, for example, my interpretation of Pretty Woman (1990), in Chapter 5, shows how the film uses specific narrative and representational strategies to contain the critique of class and gender privilege that it initially promises.

The body of this book, then, comprises detailed interpretations of the narrative and representational strategies of ten unlikely couple films and focuses on the ways in which those strategies both articulate and contain the critical potential inherent in the genre. Such detailed interpretations are necessary, for only through them does it become possible to demonstrate how a particular aspect of a film either subverts or supports a given social interest. All too often, film scholars neglect the context in which an image appears, taking its mere presence to establish a film’s politics—so that, for example, the presence of a heterosexual couple at the end of a film is taken as evidence of the film’s support of patriarchy.6 But as my readings demonstrate, nothing follows simply from the presence of an image, for the issue is how the narrative positions it and how it is received by an audience.

A second reason for offering such detailed interpretations is to show that popular films are worthy of the kinds of serious intellectual engagement philosophers have generally reserved for written texts. Because these films question the extent to which hierarchic social relationships are legitimate, they inevitably raise important questions about a wide range of philosophic issues: What role can romantic love play in the lives of human beings? How can individuals transform their lives to bring them more fully into accord with their sense of what is an appropriate life to live? Is education accomplished only through explicit instruction or are there other, perhaps more important, processes through which human beings learn? Why is our finitude—our dependence and mortality—so difficult for human beings to accept and how do we seek to avoid acknowledging it? What is the nature of human desire? What assumptions about gender structure our sexuality? To demonstrate that popular narrative films can actually address such philosophic concerns and elucidate them in their own distinctive way requires that one look at films carefully and in some detail, treating them as texts worthy of serious and sustained attention.

Still, the overriding concern of the unlikely couple film is the legitimacy of social hierarchy. Despite the range of its philosophic concerns, it is in its confrontation with issues surrounding hierarchy—What is so problematic about hierarchy? Why is it such a persistent phenomenon in human life, one so difficult to eradicate?—that the unlikely couple film establishes itself as a truly philosophic genre.

My approach to film owes a great deal to the work of Stanley Cavell. Distinctive of Cavell’s approach is the way he places film and philosophy in dialogue, according neither pride of place.7 Central to both, he argues, is a concern with the difficulties human beings have in acknowledging others as fully and completely real.8 Through nuanced readings of an impressive variety of works of literature, philosophy, and film, Cavell has demonstrated how important an issue this problem of acknowledgment has been for intellectuals and artists in the modern West.

Cavell has written at length about two groups of Hollywood films from the 1930s and 1940s—“comedies of remarriage” and “melodramas of the unknown woman”—that use romance as a means of addressing the problem of acknowledgment. In justifying his philosophical claims, Cavell shows, in a series of insightful and daring readings, that these films are both vehicles for mass entertainment and genuinely creative works of art.

Despite the sophistication of Cavell’s readings, they are beset by a fundamental inadequacy: For him, the ultimate root of the failure to acknowledge is always psychological, explicable in terms of the individual’s confrontation with elemental features of “the human situation.” As a result, his readings tend to level the social and historical settings of the texts/works he considers. Although he does, at times, admit that regard for social context can be an important consideration in interpreting a film, his analyses of how the struggle for acknowledgment presents itself consistently scant the specific sociohistorical terms through which individuals actually live that struggle.

My focus on the centrality of hierarchy in the unlikely couple film thus significantly departs from Cavell’s emphases. Although I do not deny that film tackles issues fundamental to the traditions of Western philosophy—indeed, my interpretations explicitly seek to support Cavell’s contention that they do—I insist that those issues not only arise in specific historical and social circumstances but inevitably present themselves to individuals in terms that register those specificities. As a result, the analyses of individual unlikely couple films contained in this volume are obliged to show both that the films are philosophically illuminating and that their philosophical ruminations emerge out of and are marked by these specificities of sociohistorical context.

Destabilizing Hierarchy

The guiding perspective of this study, then, is that through narratives of transgressive romance, the unlikely couple film confronts various forms of social oppression. To see exactly how the genre addresses these issues, we need a more developed understanding of its salient characteristics.

The unlikely couple film traces the difficult course of a romance between two individuals whose social status makes their involvement problematic. The source of this difficulty is the couple’s transgressive makeup, its violation of a hierarchic social norm regulating the composition of romantic couples. For example, in the context of the American South in the early decades of the twentieth century—although not only ther...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Filmography

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 The Subversive Potential of the Unlikely Couple Film

- Part 1 Class

- Part 2 Race

- Part 3 Sexual Orientation

- Bibliography

- Index