![]()

Chapter 1

The mystical experience

In discussing a mystical experience (hereinafter abbreviated to “ME”), psychoanalysts are sure to cross the threshold of psychoanalytic theory immediately and drift into the mention of God or call upon the statements found in religious and spiritual traditions. Terms have thus emerged in psychoanalysis that lack psychological precision in relation to a ME and are employed to provide labels for the genus of the experience. “Religious” is usually associated with experiences that take place in the context of Western religious practice. “Mystical” is used to describe experiences that have an Eastern connection: a merging with the godhead or other extraordinary occurrences, usually but not always disconnected from liturgical Western religion. “Spiritual” is a generalised term that is used to describe an internalised feeling state associated with religious or mystical sentiments. The word “numinous” is often invoked by psychoanalysts to describe a “spiritual” event or a feeling tone of religiosity or mysticism. For Jungians, the term “numinous” is always chosen as it was used by Jung himself as inclusive of other types.

“Mystical” is chosen here because it is a pointer to all aspects of the mystery of a ME in order to describe a subject matter that is not within expected, conscious parameters. “The intensification of religious life that characterizes most forms of mysticism culminates at times in paranormal experiences” (Idel, 1988, p. 35).

These one-size-fits-all categories of numinous, spiritual, religious, and mystical are understandable because they conveniently offer a shared notion and understood communication of the nature of these events. The categories then become easy repositories for psychoanalysis in which to place and name these occurrences that are not capable of a clear explanation. The reliance on these non-psychological categories is ironic as so much of psychoanalysis – the functioning of the ego, the structure of the unconscious – is just as mysterious yet contained neatly within theoretical structures created by the great exponents Freud and Jung. They both managed to confine it to an outlier experience of advanced souls or poorly defined excess baggage; Freud (1938/1941, p. 300) calls a ME the “obscure self-perception of the realm outside the Ego.” This has perhaps been a reason why only relatively few analysts have given it greater relevance, leaving the general categories necessary.

Analysts do not have exposure to highly evolved mystics so as to understand the passage and effect of a ME. If a person has such a life-changing experience, it is not likely that they will be in analysis; none of those who were interviewed entered psychoanalysis after their experience. If psychological issues arose for these mystics, they were understood in the context of a tradition as a necessary working through of blockages or the need to perfect meditation. For many, the idealised psychoanalytic goals were in them as a result of their practices and experiences by a marked sense of a unifying principle, a lessening of neurosis, and a reduction of fear and desire.

Patients do indeed have MEs. Few of those that are reported in the psychological literature appear to be experiences where they have created an indelible reorientation by a merging with the godhead or nothingness. Very many patients, however, participate in spiritual and religious traditions or turn to meditation and prayer and have or hope for experiences. These may be experiences of a different type or intensity than those that declared themselves mystics as they do not appear to have that same profound effect of a complete reorientation. Nevertheless, these MEs, when presented, are just as inexplicable as they occur outside the established course of the analysis and offer the possibility of bringing a new perspective to the patient.

When patients bring a ME into analysis, the experience is then contained within an analytical field where the phenomenon is as strange to them as to the analyst. It then is absolutely in the room and requires a space for it to be observed and somehow integrated. To do so, it is necessary for the analyst to understand what has occurred psychologically in order to ground it in professional theory.

The starting point for integrating a ME into psychoanalytic theory is not to drift into mystical or religious language but to keep it intact as an intra-psychic event that has occurred within the subjective experience of the patient. The psychological focus is that the ME is relevant because it has or could have an effect on consciousness – the subject matter of psychoanalysis. Words of cross-over at this time are confusing for this integration, such as Grotstein’s (2000, p. xxx) statement that “The analyst, without realizing it, is a practicing mystic.” This form of the analytic position takes it away from its actual effect on consciousness and places it in the abstract region of a mystical quality of analysis, therefore removing it from clear-eyed examination as pertaining to psychoanalytic theory and practice.

What emerges as the critical issue in psychoanalysis, either immediately or eventually, is the effect of the experience on the conscious position measured by the receptivity of the subject. It is this marker alone that will determine if a ME will have an effect on consciousness and is a question that does not need to leave psychoanalytic practice and theory. As this – the character and receptivity of the patient – is the essential question relating to the psychological effect of a ME, it is surprising that there is little, if any, evaluation of what makes a person open to a ME or how it is possible to tell if one person will make a more radical change than another or even how to help a patient make sense of it. Yet, this is the defining issue for practice: is the person with the experience able to receive it so that it has a chance to alter consciousness? Is it therefore worth keeping that experience alive in the analysis and is there anything that can be done as it fades away?

The second question may seem to run counter to the traditional, analytical attitude of the analyst’s lack of memory and desire or may appear to hint at too much interpretation or unwanted intervention. However, as with a profound dream or a dominant projection, a ME is a psychological event that is in the consulting room and is sufficiently rare and powerful that it cannot be just ignored on the basis that further dreams or psychoanalytic work will reveal what is unconscious. In fact, it is a seminal event; and, when we witness it, it is a psychological celebration that we must attend.

Psychoanalytic subject matter

It is impossible to deny, as Wilfred Bion reminds us, that there is a mysterious, underlying layer in all psychoanalytic work; there is always something beyond our understanding. We can sense it, feel it, and observe how it touches us and the patient. We completely accept that this mystery is not just an interesting backdrop but essential to the process of analysis; as the Gnostic text Pistis Sophia (Mead, 1921, ch. 133) explains, “Without the mysteries no one will enter into the realm of light, whether he be a just man or a sinner.”

Of all the mysteries that occur in an analytic session, a ME is the most specific example because, “As an experience, it claims to have encountered mystery” (Fanous and Gillespie, 2011, p. ix). As opposed to just a wide variety of unknowable mysteries that arise in endless and amorphous ways in analysis, a ME is a unique mysterious occurrence that is reported as a wondrous narrative of a singular event.

As the details of this experience may be set out in the narrative, it can appropriately be attributed by psychoanalysis to the indecipherable mission of the unconscious. As it is indeed the stuff of unconscious and a subjective experience, it deserves attention as much as any other specific source of unconscious revelation, such as a dream, a projection, or a waking fantasy. However, the professional tools that we have to work with this – the transference, projective identification, conversational methods, developmental attachment theories, and repressed wish fulfilments – cannot give us even a toehold on something that is so alien to logic and understanding. The consequence is that the experience is not given sufficient attention, or is passed off as the gift of a divine power, both as the reason for its occurrence and to account for the nature of its content.

The tendency of an analyst and patient to place a ME into a religious context rather than an eruption from the unconscious is inevitable and will always occur to some extent as it is more convenient than accepting that an alien force seemingly imposed from outside is a force arising from the inside – the deep unconscious. The mechanisms and content of the vast, deep unconscious is vaguer than the idea of a transcendent God. At least with God we can have an opinion fortified by doctrine and belief. The few psychoanalysts who have ventured into an explanation of the mystical as arising from the unconscious, such as Bion, Eigen, and Grotstein, still eventually cross back into a discussion of divine intervention (Merkur, 2010, chs. 9, 10, 12) as the real basis of the experience, as there is no easy bridge to a ME arising from unconscious forces.

The attribution of a ME to a divine source cannot be criticised but it has the effect of removing it from the probability that there was a breakthrough into consciousness of a profound message from the unconscious that deserves enquiry. Since it is utterly inexplicable, with no means to enter the reason for its breakthrough into consciousness, this helpful vessel of the grace of God is always there and may of course be all that it is, and psychoanalysis should just look on in awe and stay out of it. There are, after all, so many mystical or spiritual traditions where explanations of union with a transcendent, external godhead flow from the experiences of its adherents. These are so well defined and documented that they include a refined psychology of their own for the attainment and experience of the mystical. If the psychology is not explicit, as it is with the systematic refined explanations of the Buddhist Abhidhamma, it is at least symbolic as to psychological states, as with Hindu doctrine or Kabbalah.

A ME, no matter what its source, remains a subjective occurrence that may have a profound effect on the conscious position; it is always a psychoanalytic issue for that reason. It does not therefore require an answer as to its source but it does demand an understanding of what it means for the workings of the unconscious. This question is rarely addressed because the day-to-day work of analysis is with a patient’s struggles with shadow elements, developmental pitfalls, inter-generational trauma, or the myriad other issues that require attention. However, MEs do indeed occur in some form for some patients and cannot, in a professional sense, just be passed off as either inexplicable or grace. The recognition that a ME is also a psychological event and suitable subject matter for psychoanalysis has the effect of requiring that it receive the same attention as other experiences that affect ego consciousness.

Issues for psychoanalysis

A patient (MH) related this experience:

It was lunchtime and I was in Madison Square Park [mid-town Manhattan] and I sat down to eat my sushi on a bench by the dog run. After I finished, I looked up and there shimmering before me was the Virgin Mary. She must have been about ten feet tall. There was light coming out of her stomach area. At first, I was panicked and then, for a moment, I felt like I joined with her as if we were one and then I was filled with love and a sense that my life was fine, but, after about thirty seconds, she disappeared. She looked like my ex-girlfriend so that probably was it and I am sure it was the crabstick in the California roll that gave me the hallucination.

At the time of this session, MH was a forty-eight-year-old accountant whose presenting problem was depression that he blamed on being stuck in an office and having a stale relationship. At the time of the experience, he had been in analysis once a week for four years. He had never had such an experience before and did not for the following year. After mentioning the vision, he was adamant that talking about it was a waste of time. If I mentioned the vision, he would shake his head from side to side and say, “Crabstick.” If I even wanted to speak of the role of the crabstick, he shut down the discussion.

At the next session, I quoted to him from St Teresa of Avila (1987, p. 247): “I have never regretted having seen these heavenly visions, and I would not exchange even one of them for all the goods and delights of the world.” At another, I suggested treating the experience as a dream. He began a discussion of the contents of the experience, only to turn away and dissociate. In respect for this resistance, I did not bring it up again.

The experience itself raises many questions for psychoanalysis and offers no answers. I was drawn instantly to the experience because of my own interest in mysticism and because it reminded me of the vision of Hildegard of Bingen, the twelfth-century mystic who described a vision of the Virgin Mary as “light burst from your untouched womb like a flower on the farther side of death … Two realms become one” (Furlong, 1996, p. 100). I did my best to hide my enthusiasm. When the session with MH was over, I wrote down the questions that arose from his rejection. Was his experience a sign of him dissociating or the emergence of a psychosis? Why did it occur at this stage of the analysis? Was it a legitimate ME and, if so, what does that mean for him? How can it be brought into the consulting room, given his refusal to talk about it? Did it arise because of my own deep interest in mysticism, my countertransference and its presence in the field or even my analytic attitude? Is it relevant for the analysis at all if he refuses to discuss it or should I just expect that it will carry on to some further effect in his psyche?

The contents of his experience would neatly fit within any definition of a ME: a merging with the divine, the revelation of an absolute truth, and the vision itself. These characteristics constitute what is referred to as a “unitive” experience – a merging and becoming one with the divine – the hallmark of the ultimate ME. In fact, had MH declared that he was now a “mystic,” there would be no basis for anyone to dispute his assertion. However, his refusal to discuss it and his attribution of the experience to the crabstick makes it, arguably, not effective in the psychoanalytic process.

His rejection squarely raises the psychoanalytic issue of when such an experience is useful and a subject matter for analysis. It is fundamental that, for it to be useful, it needs to have some impact on the conscious mind; for, if the experience is not entertained by him, it ceases to have any relevance and is merely a curious, historical element in the field, more likely to interest the analyst than the patient.

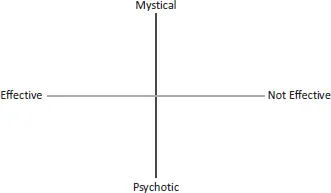

It makes particular sense that for the relational basis of psychoanalysis, a ME loses significance if it cannot be made a subject matter for both the analyst and the patient. Bion (1965/2014a, p. 169), in reference to the mystical, unknowable core of psychoanalysis – which he called “O” – explained: “In psychoanalysis, any O not common to the analyst and analysand alike, and not available therefore for transformation by both, may be ignored as irrelevant to psychoanalysis.” This would be true of any experience but for those that are caused by an external occurrence, such as a trauma or a betrayal, there is a factual basis on which to continue to base a discussion. When the experience is sudden, without a known source, and enters the realm of a unitive merging with a divine object, there is no clear entry point to investigate the occurrence. Accordingly, an examination of a ME suggests four end points that are as relevant as the starting point for any psychoanalytic examination of the event – see Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Psychoanalytic limits of a mystical experience

Between a ME at the apex and the horizontal line, there is a gradation of experience – from a full unitive experience to a lesser experience of a mystical nature. Once it descends below the line, in whatever intensity, it falls into the realm of a disorder and is more an experience that has diagnostic, rather than analytical, relevance. However, no matter where it sits on the vertical axis above that line, a ME is of no effect if it is rejected or not reported and it then crosses the horizontal axis to lose effectiveness on the vertical line. In both cases – below the horizontal line or to the right of the vertical line – it ceases to be a subject of analysis although it may be information retained by the analyst (to what end, though, is unclear). To be a ME that is effective and relevant for psychoanalysis, it must stay above the horizontal line and remain effective and not cross the vertical line.

In the case of MH, it did not appear from subsequent sessions that the vision was a result of a disorder; it remained above the horizontal line. There was no disturbance to his pattern of thinking, no disquiet, and no negative reaction to his experience. It failed the test of effectiveness along the horizontal line, however, as it crossed the vertical line; and, at most, it confirmed his initial dream. In this dream, he was in an unfamiliar house and afraid to go up to the attic. Instead, he sat comfortably in a chair on the ground floor and did not want to get up. The dream and his reluctance to move could be attributed to many complexes and issues, but the reality was that the possible breakthrough in the experience did not find a place in the consulting room.

It is possible, in this diagrammatic formulation, to assert that there are two meaningful elements for consideration in investigating the depth psychology of the ME. Is the experience to be classified as a ME above the horizontal line and therefore of interest? And, secondly, will it have a possible impact on consciousness by staying in the analysis? Both are necessary for the experience to be considered a ME that is relevant for psychoanalysis.

Characteristics of a mystical experience

A ME has as many variations in content as there are those who have had such an experience. However, the discussions over centuries have strived for a complete, exhaustive, and inclusive explanation having specific characteristics because it is equated with the highest goal of human accomplishment as the realisation of a complete unity or merger with the divine or formlessness and a consequent loss of individuality (Stace, 1960, p. 11). Bharati (197682, p. 63) calls this highest level of ME a “zero experience” – a loss of ego identity in the merger with the cosmic ground. The equivalent Buddhist expression is sunyata, meaning “zero-ness.” Although the Hindu and Buddhist traditions have different orientations, the description of the experience is essentially the same. It is described (Noh, 1977, p. 17) more graphically as:

You are immediately non-existent, in the sense that you transcend the realm of objectified experience and enter the Void of the Absolute, Non-existence. Thus, you transcend all forms of being, you are totally unconditioned. You exist beyond any form of awareness or self-consciousness. There is nothing left which can be identified as “I”; everything that is “winks out,” ceases to be, radically stops. There is no sensation of time – it is an eternal moment.

This narrative of a unitive ME invokes poet...