eBook - ePub

Experimental Film and Anthropology

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Experimental Film and Anthropology

About this book

Experimental Film and Anthropology urges a new dialogue between two seemingly separate fields. The book explores the practical and theoretical challenges arising from experimental film for anthropology, and vice versa, through a number of contact zones: trance, emotions and the senses, materiality and time, non-narrative content and montage. Experimental film and cinema are understood in this book as broad, inclusive categories covering many technical formats and historical traditions, to investigate the potential for new common practices. An international range of renowned anthropologists, film scholars and experimental film-makers engage in vibrant discussion and offer important new insights for all students and scholars involved in producing their own films. This is indispensable reading for students and scholars in a range of disciplines including anthropology, visual anthropology, visual culture and film and media studies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Experimental Film and Anthropology by Arnd Schneider, Caterina Pasqualino, Arnd Schneider,Caterina Pasqualino in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

EXPERIMENTAL FILM AND ANTHROPOLOGY

Caterina Pasqualino and Arnd Schneider

In this book, we seek to challenge and overcome a broad realist–narrative paradigm that—with few exceptions—has dominated visual anthropology so far. While, on the whole, visual anthropology had several important innovators (notably, Jean Rouch, Robert Gardner, and David MacDougall),1 and, at certain points in its history is influenced by innovative movements in film-making (including documentary film-making), such as Italian Neo-Realism, cinéma vérité, and direct cinema, none of these innovators engaged with what were (and are) film’s own experimental avant-gardes. By this we mean the genealogy of experiments with film’s form and material in several pre- and post-avant-garde movements (such as in abstract, futurist, surrealist, absolute, and structuralist film).2

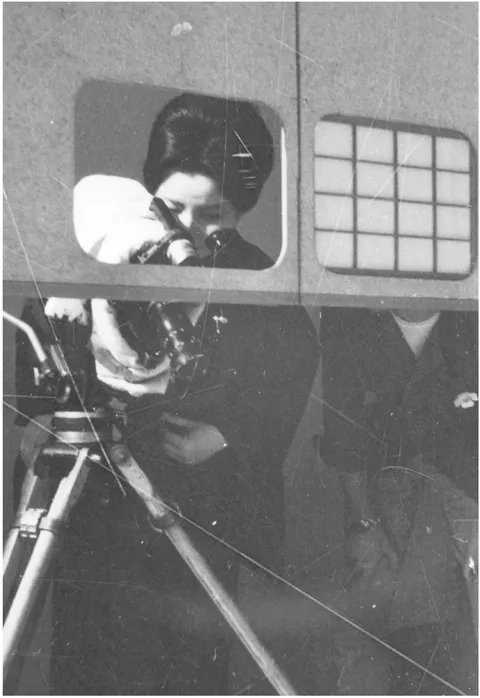

We should stress that our approach is deliberately impure and eclectic. We use “film,” rather unapologetically, to signify moving image products in the broadest sense, including all post-analog formats. On occasion, for specific theoretical reasons, our arguments are indeed linked to analog films, but not exclusively. Also, we focus principally on moving image products or artefacts—which is the reason why we prefer the term “film” over “cinema.” However, a broader argument could perhaps be constructed for the relation between anthropology and experimental cinema, including audience reception, and several contributors point to that direction (for instance Caterina Pasqualino, Christian Suhr, and Rane Willerslev). Experiment, of course, has been used also in another, more literal sense of an orderly arranged test, trial, or procedure, in anthropological film-making. Thus experiments with film have also been used in anthropology of what on the surface seems to be a more positivist understanding of science and the camera as a research tool, but what in fact reflected an eclectic mix of influences from natural and life sciences, psychology, psychiatry, behaviorism, and kinesics (for instance, the films of Ray Birdwhistell).3 Here the camera was introduced as an investigative agent in the experimental design and arrangement of the film-work, in order to elicit responses among the filmed subjects.4 Stemming from a long line of precedents, including Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson’s famous work on the Balinese “character,” the broader agenda was to study visual communication (often non-verbal) cross-culturally. However, these approaches were heterogenic and cannot be subsumed under one paradigm, even for the work of one film-maker or film-making team. For instance, in the case of the Mead–Bateson collaboration, these included different emphases in film-making: for Mead the camera was primarily an objective, disengaged research tool, whereas for Bateson the hand-held camera allowed close visual engagement in social action. In their films, influences of both approaches are present which also characterize differently the entire oeuvre. Some films (focusing often on childhood behavior) suppose a more disengaged, objective scientific documentation, whereas in others a more interpretive and creative style dominates (such as Trance and Dance in Bali, 1952, and Learning to Dance in Bali, 1978).5 The principal idea that the camera is a research tool for observation was reflexively applied and developed through the famous experiment by Sol Worth and John Adair of letting the Navajo film themselves.6 Donald and Ronald Rundstrom’s carefully arranged experimental design of sequences in their film (with film-maker Clintum Bergum) The Path (1971)—and detailed study guide—on the Japanese tea ceremony is based on and incorporates the philosophy and point of view of the practitioners. The hostess of the ceremony helped to frame shots (Figure 1.1), and significantly, the last sequence of The Path is also a proper experiment in film-making worthy of avant-garde traditions with subtle superimpositions of the implements and gestures in the tea ceremony, both arranged and observed (Figure 1.2).7

To take on the notion of experiment is important for visual anthropology, and anthropology at large, for a number of reasons. While the Writing Culture8 critique has led to experimentation with text, the visual side had been largely neglected, and visual anthropology followed principally narrative traditions, omitting thereby from the canon experimental works (for instance by Juan Downey, Trinh T. Minh-ha, and Sharon Lockhart) which problematized closeness and distance to the ethnographic subject and the multiple viewpoints of the participant observer.9 An examination of experimental film traditions has obvious implications for anthropo-logical film practice which are taken up by several contributors to our volume. For instance, Kathryn Ramey writes about the seminal camera-less animation work of Robert Ascher; Barbara Glowczewski on the reasons that led her to abandon experimental film practice with Australian Aborigines; and Jennifer Heuson and Kevin T. Allen explore the asynchronicities of sound and image in their experimental film practice. However, as Arnd Schneider has recently argued, beyond its practical value experimental film is also good to think with for anthropologists, since it questions fundamentally the material processes of visual perception.10 Experimental film, especially in its 1960s and 1970s incarnations of so-called “structuralist” or “materialist” film (which referenced earlier twentieth-century traditions of abstract and absolute film) interrogated fundamental issues, such as film time (the length of a film) vs. experienced time, narration, the apparatus (e.g. camera, and projection

Figure 1.1 Hostess Soho Uyeda (Sowa Kai Omote Senke School of Tea), framing a shot during the shooting of The Path, Donald Rundstrom, Ronald Rundstrom, Clintum Bergum, USA, color, sound, 16 mm, 1971. Courtesy of Ronald Rundstrom.

Figure 1.2 Still image from The Path, Donald Rundstrom, Ronald Rundstrom, Clintum Bergum, USA, color, sound, 16 mm, 1971. By kind permission of Ronald Rundstrom, digital screen grab courtesy of Jieh Hsiang, National Taiwan University.

devices), and the materiality of film itself. These essential tenets of experimental film suggest a number of implications, and pose some questions for anthropology, such as film as a material object rather than experienced time,11 or in the words of Nicky Hamlyn the differences between what films are (about their narration’s subject in mainstream film), or what they do (in experimental film).12 Film (especially analog) is literally a medium that comes between us and the perceived world (i.e. our senses, perception, and representation).13 Unlike “classical” cinema, the intentions of which are based on narrative, experimental film does not entertain the viewer with a story. In contrast, it invites the spectator to undergo a visual and auditory experience we might describe as a performance.

Experimental film is to a certain degree about what goes on during projection inside the viewer’s head14—an interesting link to the notions of the virtuality of ritual, or the compositional dimensions—dimensions that condition particular intentionalities in ritual and performance.15

However, we should make it clear from the outset that our use of “experiment,” and (and hence “experimental film”) is somewhat broader than that used by film historians, and no attempt is made here to engage with the history of experimental film in a comprehensive or systematic way.16 Rather, in the context of this book, we take experiment to mean more narrowly experiments with form (which, of course, in an important conceptual twist, becomes “content” for some experimental filmmakers), and, in a broader sense, any subversion of genre conventions.

With such a subversive agenda, we make deliberate and selective choices which are set against the foil of visual anthropology, and anthropology at large. Therefore, our use of examples with reference to experimental film history is admittedly eclectic and partial. This is not to say that our arguments are irrelevant to experimental film-makers, but the vantage point inevitably remains anthropology. Indeed one would be curious what the reception of an anthropological take on experimental film would be among experimental film-makers and their critics. On the few occasions when the two fields did overlap, in criticism and scholarship (one thinks of Catherine Russell)17 and in practice (famously Maya Deren), this interdisciplinary impetus came from within filmic tradition, not anthropology. Significantly, Maya Deren’s writing of Divine Horsemen, set up as a more formal ethnography, was kept separate from her experimental film practice, while with hindsight the two endeavors did influence each other, testified through not only the artistic sensibility in the writing of Divine Horsemen but also Deren’s footage shot in Haiti (and only posthumously edited by her husband Teiji Ito).18

Acknowledging these important precedents, but set at a different contemporary juncture, our book is an open invitation to experimental film-makers to come into dialogue with anthropology. In fact, to some degree, this is already happening with the work of Karen Mirza and Brad Butler, Laurent van Lancker, and others.19

Disrupting Realist–observational Narrative

Of late, there has also been a renewed engagement with film theory beyond realist paradigms by anthropologists. Dziga Vertov famously claimed that the cine camera, and all techniques involved in film, that is what he called the “Kino Eye,” can reveal things not normally visible to the naked human eye—a postulate which has informed many strands of experimental film-making.20 “Can film show the invisible?” is the main title of a recent article by anthropologists and film-makers Rane Willerslev and Christian Suhr, where they argue, coming from a broadly phenomenological perspective, that beyond observational film genres in ethnographic film-making, montage film (especially in the traditions of Dziga Vertov and Sergei Eistenstein) can evoke hidden dimensions of ethnographic reality.21 It follows from this that ethnographic film indeed is in need of a “radical shock therapy,” the term Suhr and Willerslev apply to montage work disrupting realist– observational narrative,22 and also use as the leitmotif for their animated discussion of montage in the contribution to our book.

However, in one sense, experimental film in its narrower “form as content” version had already given a very specific answer to the question of the “invisible,” by focusing on the invisible aspects of film itself, i.e. frame, surface, and print stock. The “mistakes” made in ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Contributors

- 1. Experimental Film and Anthropology

- 2. Stills that Move: Photofilm and Anthropology

- 3. Experimental Film, Trance and Near-death Experiences

- 4. Contemporary Experimental Documentary and the Premises of Anthropology: The Work of Robert Fenz

- 5. Our Favorite Film Shocks

- 6. Do No Harm—the Cameraless Animation of Anthropologist Robert Ascher

- 7. Asynchronicity: Rethinking the Relation of Ear and Eye in Ethnographic Practice

- 8. Memory Objects, Memory Dialogues: Common-sense Experiments in Visual Anthropology

- 9. Beyond the Frames of Film and Aboriginal Fieldwork

- 10. Visual Media Primitivism: Toward a Poetic Ethnography

- 11. From the Grain to the Pixel, Aesthetic and Political Choices

- Index of Names