- 194 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

What is masculinity? Drawing on psychoanalysis and an understanding of ideology, Easthope shows how the masculine myth forces men to try to be masculine and only masculine, denying their feminine side. In an original contribution to the understanding of gender, he analyzes masculinity as it is represented in a wide range of mass media --films, television, newspapers, pop music, and pop novels. Why are two men in a John Wayne western more concerned with each other than with the women in their lives? Is aggressive male banter a sign that men hate or love each other? Why does a jealous man always have to see his rival? Written in lively, witty, and accessible style, What a Man's Gotta Do is certain to become controversial but essential reading.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access What a Man's Gotta Do by Anthony Easthope in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Media Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

BASIC MASCULINITY

THE MYSTERIOUS

PHALLUS

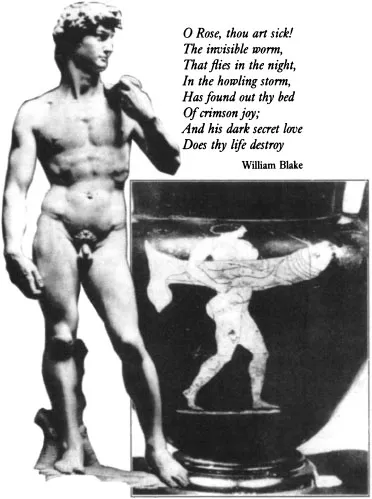

An ordinary Greek vase for storing wine or grain is decorated, as a matter of course, with an image of a naked woman marching off with something under her arm that resembles a fish or a tree-trunk but which is really a phallus. Margaret Walters in The Nude Male remarks of the image that ‘it is not clear whether her intentions are religious or lustful’. The second image shows Michelangelo’s carving of David from the biblical story of David and Goliath. It is without doubt the most famous sculpture of a male nude in the Renaissance tradition, and has inspired a whole tradition of representation of the young and athletic male body down to Tarzan and Superman. What is reproduced here comes from a postcard sold to tourists in Florence for less than 10p.

Although both images come from the main line of Western culture, a huge distance separates them. Greek society publicly celebrates male power through the symbol of the penis erect; the Christian and Renaissance world hides it away. David’s right hand is larger than life but not his penis. The Greek phallus is displayed to attract women, but it is also there for men since in this society male homosexual desire is admitted explicitly. After that it goes underground and becomes sublimated into something else.

Greek Vase with Phallus

From the fifth century B.C., as Margaret Walters says, the male body becomes a normal image in art. Idealized in the form of gods – Zeus the father, Apollo the perfect son – patriarchal power is openly on view. Satyrs, often fat and hairy, are shown with huge erections; gigantic phalluses are carried at religious festivals honouring Dionysus. Instead of portrayals of the Virgin Mary or Jesus of the Sacred Heart, people put on their doorways a good-luck charm consisting of a man’s head and an erect penis. This also forms the centrepiece for sculptures honouring the fertility god, Priapus. As a garden ornament he was used sometimes as a scarecrow to frighten birds. Instead of a Disney gnome ancient lawns were protected by a rigid male member. The Roman god Fascinus, represented simply as an erect penis, was carried around by people as a good-luck charm instead of a St Christopher. Images of the phallus could be seen everywhere. There was no secret about male dominance.

This is a masculinity which swings both ways. The phallus is exhibited to men and women as an object of desire. In the framework of psychoanalysis the male individual contains both a masculine aspect which desires the feminine and a feminine aspect which desires the masculine. In Greek culture masculinity is defined through both heterosexual and homosexual desire.

In a text which stands right at the beginning of the Western tradition, The Symposium, Plato imagines or recalls a dinner party that took place just before 400 B.C. As well as Socrates, the guests include the comic dramatist Aristophanes. It is an all-male party. Deciding not to drink too much this particular evening because they are hung-over from the night before, the men send out the last woman, a flute-girl, so that they can talk among themselves about the nature of love.

There are three main speeches. Aristophanes tells a story, that originally everyone was joined to someone else in a four-legged, two-headed body with two sets of genitals (they ran by turning cartwheels). But they got too strong for Zeus so he cut them all in half. And this is why love takes the form it does, since everyone desires his or her original partner, whether male and female, male and male or female and female.

Socrates opposes this cheerful pluralism. No women are present but nevertheless he quotes the views of a woman, Diotima, about love. Through her voice Socrates advocates the sublimation of desire – it should develop from lust for real bodies to an abstract love for ‘universal beauty’. The party ends with a speech by Alcibiades, a handsome, brilliant but unreliable politician. He arrives drunk but confirms Socrates’s defence of chastity because, so he says, he had tried to make love with him once, even got into bed with him, but hadn’t been able to seduce him.

Perhaps it would be wrong to take Plato’s work too seriously. Aristophanes is a comedian, Alcibiades is drunk. But still male homosexual desire is acknowledged as part of masculinity, not denied. Afterwards the view of Socrates wins out. As Western culture comes under the influence of Christianity the symbol of the erect penis is banished and homosexual desire is turned down other pathways.

‘David’ and Sublimation

Male power does not disappear along with public representations of the phallus. Far from it – patriarchy becomes more pervasive and far-reaching when it tries to be invisible. David’s flaccid penis appears to be merely one part of his anatomy, carefully concealed by being in realistic proportion to the rest. But his whole body presents masculinity as though it were equivalent to confident humanity itself.

Michelangelo’s naked statue shocked its contemporaries. Soon after it was set up in the town square in 1504 it was stoned one night, though it is not certain whether this was done by Michelangelo’s political opponents or because the naked genitals were found so disturbing. In the period after the Council of Trent in 1563 a big effort was made to suppress nakedness in art, both male and female. There was, for example, a move to destroy Michelangelo’s fresco of The Last Judgement on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican. And a painter, Daniel da Volterra, was paid to paint over the represented genitals.

Threatened more by industrial pollution than prudery, the David was moved inside in 1873 to its present setting in the Accademia. Designed for the public square, its enormous height seems excessive indoors. It reproduces the Greek tradition of portraying a perfect young man. But while the Greek statues represent gods, serene and unified, appearing the same from whatever point they are viewed, David is human, mortal and contradictory. Seen from the front, with his face in profile, he is cool and relaxed. But from any other angle the twist of the neck seems strained, the frown uncertain. This ambiguity gives the figure great inwardness, an inner tension expressed across the whole of the body. His phallic potential is suggested everywhere but not explicitly stated anywhere.

The effect is partly a historical one. In the context of the biblical narrative David becomes a character in a bourgeois narrative. I Samuel 17 says that ‘the king will enrich’ the man who destroys Goliath, and David is the humble shepherd boy who makes good through his individual ability, in this case with a slingshot. He is also the submissive son who kills the uncircumcised Philistine and cuts off his head ‘in the name of the Lord’, in the name of the symbolic father. He stands for God’s invisible erection.

With the suppression of public display of the phallus, masculine phallic power becomes at the time of the Renaissance an inward and spiritual force. And male homosexual desire becomes increasingly sublimated into forms of social obligation.

For psychoanalysis there is no disinterested motive, no unselfish love, nothing innate that would make us co-operate and work for the sake of others. That has to be developed. Flowing out of a single reservoir of energy, or libido, the two main drives take the form of love for oneself (narcissism) or love for another (sexual desire). This inevitably brings the individual into some conflict with social order and the law, for you either want something for yourself or desire what you can’t have. Sublimation is a crucial means to resolve such conflicts.

Sexual drive can be transformed into narcissism, self-love. For example, it only takes a slight touch of ’flu for you to lose your sexual interest – the ego needs all the libido it can get and keeps it for itself. Sublimation works rather like that. If sexual drive is withdrawn into the ‘I’ it becomes partly desexualized and can be directed to a non-sexual end. The classic example of sublimation is art itself. The ‘I’ is able to tame and master sexual desire by creating or looking at pictures of desirable objects. Or someone frustrated by an unhappy sexual relationship will find an outlet by working very hard. Thus, so it’s argued, sublimation is fundamental to the social order, transforming unacceptable sexual drive into something more conventional.

Clearly enough male heterosexual desire can be led to cooperate with the social order through the institution of marriage. But this does not account for the other side of masculinity, for male homosexual desire. Desexualized, sublimated love for other men becomes available to form the male bond, enabling men to work together for each other.

This is the logic behind Freud’s otherwise extraordinary – and repeated – assertions that modern patriarchal society is based upon sublimated male homosexual desire. It is vividly illustrated by the Renaissance statue of David. For what is his desire? It is surely not sexual. He exercises a spiritual and inward self no Greek statue ever shows, and through this narcissistic dimension his sexual desire is transformed into social duty. He is not there for women but for himself and his father.

Michelangelo’s David is an exceptional image of a nude male. After the Renaissance the nude is generally female, not male. And representation of the penis, whether erect or not, continues to be forbidden down to the twentieth century, as Margaret Walters recalls. In 1916 an explicitly phallic statue by Brancusi was banned from an exhibition in Paris. In 1933 a portfolio of Michelangelo’s nudes was seized by customs in New York for being ‘shocking pornography’. Jim Dine’s exhibition of watercolours showing a variety of penises was raided and shut down by London police in 1966. In 1968 the Kronhausen’s famous erotic exhibition manifested the usual inhibition about representing the phallus, even though it took place in Sweden.

On 6 June 1985 the Guardian newspaper reported the following incident. An artist, John Hewett, had been asked to paint ‘something sporting and Grecian’ for a swimming pool in the nurses’ home of St Bartholomew’s Hospital in London. He had done so, but after the hospital had received ‘numerous complaints’ the mural was covered with a heavy coat of whitewash on the orders of the hospital administrator. This was because, so he said, it had shown a ‘full frontal reclining male surrounded by other naked males’. A few days later Sian Hillier SRN wrote to the paper asking whether ‘young and innocent nurses’ would now be issued with blindfolds for use when ‘handling the unmentionable object’.

This newspaper story confirms two things about the modern myth of masculinity. One is that the phallus must remain unseen if it is to keep its power. The other is that men are more concerned about seeing ‘the unmentionable object’ than women.

FATHERS AND SONS

Red River, directed by Howard Hawks (1948)

In 1851, Thomas Dunson (John Wayne) leaves behind a wagon train and Fen, the woman he loves, to start up his own herd of cattle. In the distance he sees the wagons attacked by Indians and knows Fen is dead. A boy, Matthew Garth (Montgomery Clift), escapes and together he and Dunson cross the Red River. Fourteen years later, having found land, they have built up the largest herd in Texas. But after the Civil War there is no market for beef in the south so Dunson decides to drive them north to the railroad at Missouri.

At first the drive goes well. But one night there is a stampede and a man is killed. Dunson decides to whip the man responsible for frightening the cattle. The man goes for his gun and Matthew shoots him in the shoulder to prevent Dunson shooting him in the heart. Later three other men revolt against Dunson’s leadership and he is forced to shoot them. Another three run off taking some food and a gunman is sent to bring them back. Meanwhile the herd crosses the Red River.

When two of the runaways are caught Dunson proposes to hang them for theft. Led by Matthew, the cowboys gang up against Dunson, take his herd and ride for Abilene (not Missouri), leaving Dunson behind. He promises to pursue them and kill Matthew. Under Matthew’s leadership they rescue a wagon train from Indians and Matthew falls in love with Tess Millay. They also find the railroad and Abilene where Matthew makes a good deal to sell the cattle, keeping the money for Dunson. However, Dunson catches up with them, shoots at Matthew – who won’t shoot back – until they have a fistfight. This is stopped by Tess Millay threatening them both with a gun. The men are reconciled and Dunson incorporates M for Matthew into the brand of his ranch.

A father, said Stephen, battling against hopelessness, is a necessary evil

James Joyce, Ulysses

Where should we look for fathers and sons if not in the classic Western? Red River is the classic cowboy film as well, the story of the cattle drive, widely shown in the cinema at the time, now often on television. It even has a repeated song with a chorus of ‘Yippee Yi Yay’ Filmed with an epic quality, especially in the crossing of the Red River, the film says something about the founding of America – indeed perhaps about capitalism itself. And the thousand-mile three-month drive suggests, albeit in a glamorized form, the nature of work in general as an active male enterprise.

The Western is a particularly masculine genre and Red River is an archetypal male-bond movie. Conflict between the men is acted out with a symbolic phallus – who has the fastest draw? Comedy consists of rough male banter. For example, playing poker, Groot, the garrulous old cook (Walter Brennan), loses his false teeth to an Indian in the company. When at one point on the trail he asks for them back because they ‘help to keep the dust outta my mouth’ Quo the Indian replies, ‘Keep mouth shut. Dust not get in.’ When women do appear in the film, at the beginning and the end, their performance is stilted, perhaps because they are required to act and talk more like men than women. Women are kept to the margins in Red River, even though in the end they are what is at stake, what is fought for.

Male Sexual Identity

There is a story that George Washington never wanted to found the United States. All he wanted was a commission in the British Army but when this was refused he said, ‘OK, I’ll get my own damn country and my own damn army.’ Psychoanalysis understands the construction of male sexual identity along rather similar lines. The male infant, like every infant, actively seeks to keep the mother and her love for himself. To become a heterosexual man the little boy must transfer his love from the mother to another adult woman, a figure that for convenience – and with no necessary commitment to the institution of marriage – may be termed ‘the bride’. To become a heterosexual woman the little girl must transfer her love from the mother to the father and then to the figure of the bridegroom. The path to adult, heterosexual identity is not symmetrical but both sexes begin by actively seeking the mother. Both must give up the mother from fear of castration.

All this is a symbolic process. No act of castration is literally carried out – it’s a matter of drive, not instinct. It would solve a lot of problems if psychoanalysis could simply describe castration as the loss of the mother, as lack. However, this loss is symbolized by the idea of loss of the genitals, the worst thing in the world. It is worse than death, says Freud, because fear of death is only a shadow of this. In wanting the mother the little boy comes into competition with the father and feels threatened with castration. Because of this he surrenders one object, the mother, and comes to desire another, the bride. In so doing he is able to identify with the father and prepare to take his own place as a father.

This is the ideal model but it hardly ever works out like that. On the path to adult heterosexual desire the little boy has to find a way between two dangers. If he has been too submissive to the father he must challenge him for the mother’s love, otherwise he’ll never come to take the role of the father. On the other hand, if he attacks the father too much and refuses to accept castration, he remains rebellious and infantile, unable to give up his attachment to the mother. The two possibilities correspond to the two sides of the little boy’s sexuality, or rather bisexuality. His heterosexual side seeks the mother and opposes the father. But his homosexual side tries to avoid the father’s threat by taking the mother’s place and becoming the object of the father’s love.

It is exactly this divided sexuality that the myth of masculinity wants to deny. Although men are always both masculine and feminine, the myth demands that they should be mascu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I: Basic Masculinity

- Part II: The Masculine Ego

- Part III: Masculinity in Action

- Part IV: The Same Sex

- Part V: Masculine/Feminine

- The Masculine Myth

- List of Texts

- Further Reading

- About the Author

- Index