- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

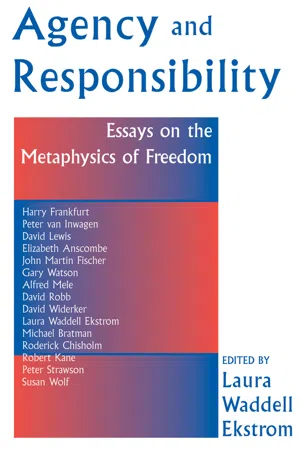

A companion volume to Free Will: A Philosophical Study, this new anthology collects influential essays on free will, including both well-known contemporary classics and exciting recent work. Agency and Responsibility: Essays on the Metaphysics of Freedom is divided into three parts. The essays in the first section address metaphysical issues concerning free will and causal determinism. The second section groups papers presenting a positive account of the nature of free action, including competing compatibilist and incompatibilist analyses. The third section concerns free will and moral responsibility, including theories of moral responsibility and the challenge to an alternative possibilities condition posed by Frankurt-type scenarios. Distinguished by its balance and consistently high quality, the volume presents papers selected for their significance, innovation, and clarity of expression. Contributors include Harry Frankfurt, Peter van Inwagen, David Lewis, Elizabeth Anscombe, John Martin Fischer, Michael Bratman, Roderick Chisholm, Robert Kane, Peter Strawson, and Susan Wolf. The anthology serves as an up-to-date resource for scholars as well as a useful text for courses in ethics, philosophy of religion, or metaphysics. In addition, paired with Free Will: A Philosophical Study, it would form an excellent upper-level undergraduate or graduate-level course in free will, responsibility, motivation, or action theory.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Agency And Responsiblity by Laura Ekstrom in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

PhilosophySubtopic

Philosophy History & TheoryPart I

The Metaphysical Issues: Free Will and Causal Determinism

1

The Incompatibility of Free Will and Determinism

PETER VAN INWAGEN

In this paper I shall define a thesis I shall call 'determinism', and argue that it is incompatible with the thesis that we are able to act otherwise than we do (i.e., is incompatible with 'free will'). Other theses, some of them very different from what I shall call 'determinism', have at least an equal right to this name, and, therefore, I do not claim to show that every thesis that could be called 'determinism' without historical impropriety is incompatible with free will. I shall, however, assume without argument that what I call 'determinism' is legitimately so called.

In Part I, I shall explain what I mean by 'determinism'. In Part II, I shall make some remarks about 'can'. In Part III, I shall argue that free will and determinism are incompatible. In Part IV, I shall examine some possible objections to the argument of Part III. I shall not attempt to establish the truth or falsity of determinism, or the existence or nonexistence of free will.

I

In defining 'determinism', I shall take for granted the notion of a proposition (that is, of a non-linguistic bearer of truth-value), together with certain allied notions such as denial, conjunction, and entailment. Nothing in this paper will depend on the special features of any particular account of propositions. The reader may think of them as functions from possible worlds to truth-values or in any other way he likes, provided they have their usual features. (E.g., they are either true or false; the conjunction of a true and a false proposition is a false proposition; they obey the law of contraposition with respect to entailment.)

Our definition of 'determinism' will also involve the notion of 'the state of the entire physical world' (hereinafter, 'the state of the world') at an instant. I shall leave this notion largely unexplained, since the argument of this paper is very nearly independent of its content. Provided the following two conditions are met, the reader may flesh out 'the state of the world' in any way he likes:

(i) Our concept of 'state' must be such that, given that the world is in a certain state at a certain time, nothing follows logically about its states at other times. For example, we must not choose a concept of 'state' that would allow as part of a description of the momentary state of the world, the clause, '... and, at t, the world is such that Jones's left hand will be raised 10 seconds later than t.'

(ii) If there is some observable change in the way things are (e.g., if a white cloth becomes blue, a warm liquid cold, or if a man raises his hand), this change must entail some change in the state of the world. That is, our concept of 'state' must not be so theoretical, so divorced from what is observably true, that it be possible for the world to be in the same state at t1 and t2, although (for example) Jones's hand is raised at t1 and not at t2.

We may now define 'determinism'. We shall apply this term to the conjunction of these two theses:

- (a) For every instant of time, there is a proposition that expresses the state of the world at that instant.

- (b) If A and B are any propositions that express the state of the world at some instants, then the conjunction of A with the laws of physics entails B.

By a proposition that expresses the state of the world at time t, I mean a true proposition that asserts of some state that, at t, the world is in that state. The reason for our first restriction on the content of 'state' should now be evident: if it were not for this restriction, 'the state of the world' could be defined in such a way that determinism was trivially true. We could, without this restriction, build sufficient information about the past and future into each proposition that expresses the state of the world at an instant, that, for every pair of such propositions, each by itself entails the other. And in that case, determinism would be a mere tautology, a thesis equally applicable to every conceivable state of affairs.

This amounts to saying that the 'laws of physics' clause on our definition does some work: whether determinism is true depends in the character of the laws of physics. For example, if all physical laws were vague propositions like 'In every nuclear reaction, momentum is pretty nearly conserved', or 'Force is approximately equal to mass times acceleration', then determinism would be false.

This raises the question, What is a law of physics? First, a terminological point. I do not mean the application of this term to be restricted to those laws that belong to physics in the narrowest sense of the word. I am using 'law of physics' in the way some philosophers use 'law of nature'. Thus, a law about chemical valences is a law of physics in my sense, even if chemistry is not ultimately 'reducible' to physics. I will not use the term 'law of nature' because, conceivably, psychological laws, including laws (if such there be) about the voluntary behavior—of rational agents, might be included under this term.1 Rational agents are, after all, in some sense part of 'Nature'. Since I do not think that everything I shall say about laws of physics is true of such 'voluntaristic laws', I should not want to use, instead of 'laws of physics', some term like 'laws of nature' that might legitimately be applied to voluntaristic laws. Thus, for all that is said in this paper, it may be that some version of determinism based on voluntaristic laws is compatible with free will.2 Let us, then, understand by 'law of physics' a law of nature that is not about the voluntary behavior of rational agents.

But this does not tell us what 'laws of nature' are. There would probably be fairly general agreement that a proposition cannot be a law of nature unless it is true and contingent, and that no proposition is a law of nature if it entails the existence of some concrete individual, such as Caesar or the earth. But the proposition that there is no solid gold sphere 20 feet in diameter (probably) satisfies these conditions, though it is certainly not a law of nature.

It is also claimed sometimes that a law of nature must 'support its counterfactuals'. There is no doubt something to this. Consider, however, the proposition, 'Dogs die if exposed to virus V'. The claim that this proposition supports its counterfactuals is, I think, equivalent to the claim that 'Every dog is such that if it were exposed to virus V, it would die' is true. Let us suppose that this latter proposition is true, the quantification being understood as being over all dogs, past, present, and future. Its truth, it seems to me, is quite consistent with its being the case that dog-breeders could (but will not) institute a program of selective breeding that would produce a sort of dog that is immune to virus V. But if dog-breeders could do this, then clearly 'Dogs die if exposed to virus V' is not a law of nature, since in that case the truth of the corresponding universally quantified counterfactual depends upon an accidental circumstance: if dog-breeders were to institute a certain program of selective breeding they are quite capable of instituting, then 'Every dog is such that if it were exposed to virus V, it would die' would be false. Thus a proposition may 'support its counterfactuals' and yet not be a law of nature.

I do not think that any philosopher has succeeded in giving a (nontrivial) set of individually necessary and jointly sufficient conditions for a proposition's being a law of nature or of physics. I certainly do not know of any such set. Fortunately, for the purposes of this paper we need not know how to analyze the concept 'law of physics'. I shall, in Part III, argue that certain statements containing 'law of physics' are analytic. But this can be done in the absence of a satisfactory analysis of 'law of physics'. In fact, it would hardly be possible for one to provide an analysis of some concept if one had no preanalytic convictions about what statements involving that concept are analytic.

For example, we do not have to have a satisfactory analysis of memory to know that 'No one can remember future events' is analytic. And if someone devised an analysis of memory according to which it was possible to remember future events, then, however attractive the analysis was in other respects, it would have to be rejected. The analyticity of 'No one can remember future events' is one of the data that anyone who investigates the concept of memory must take account of. Similarly, the claims I shall make on behalf of the concept of physical law seem to me to be basic and evident enough to be data that an analysis of this concept must take account of: any analysis on which these claims did not 'come out true' would be for that very reason defective.

II

It seems to be generally agreed that the concept of free will should be understood in terms of the power or ability of agents to act otherwise than they in fact do. To deny that men have free will is to assert that what a man does do and what he can do coincide. And almost all philosophers3 agree that a necessary condition for holding an agent responsible for an act is believing that that agent could have refrained from performing that act.4 There is, however, considerably less agreement as to how 'can' (in the relevant sense) should be analyzed. This is one of the most difficult questions in philosophy. It is certainly a question to which I do not know any nontrivial answer. But, as I said I should do in the case of 'law of physics', I shall make certain conceptual claims about 'can' (in the 'power' or 'ability' sense) in the absence of any analysis. Any suggested analysis of 'can' that does not support these claims will either be neutral with respect to them, in which case it will be incomplete, since it will not settle all conceptual questions about 'can', or it will be inconsistent with them, in which case the arguments I shall present in support of these claims will, in effect, be arguments that the analysis fails. In Part IV, I shall expand on this point as it applies to one particular analysis of 'can', the well-known 'conditional' analysis.

I shall say no more than this about the meaning of 'can'. I shall, however, introduce an idiom that will be useful in talking about ability and inability in complicated cases. Without this idiom, the statement of our argument would be rather unwieldy. We shall sometimes make claims about an agent's abilities by using sentences of the form:

S can render [could have rendered] ... false.

where '...' may be replaced by names of propositions.5 Our ordinary claims about ability can easily be translated into this idiom. For example, we translate:

He could have reached Chicago by midnight.

as

He could have rendered the proposition that he did not reach Chicago by midnight false.

and, of course, the translation from the special idiom to the ordinary idiom is easy enough in such simple cases. If we were interested only in everyday ascriptions of ability, the new idiom would be useless. Using it, however, we may make ascriptions of ability that it would be very difficult to make in the ordinary idiom. Consider, for example, the last true proposition asserted by Plato. (Let us assume that this description is, as logicians say, 'proper'.) One claim that we might make about Aristotle is that he could have rendered this proposition false. Now, presumably, we have no way of discovering what proposition the last true proposition asserted by Plato was. Still, the claim about Aristotle would seem to be either true or false. To discover its truth-value, we should have to discover under what conditions the last true proposition asserted by Plato (i.e., that proposition having as one of its accidental properties, the property of being the last true proposition asserted by Plato) would be false, and then discover whether it was within Aristotle's power to produce these conditions. For example, suppose that if Aristotle had lived in Athens from the time of Plato's death till the time of his own death, then the last true proposition asserted by Plato (whatever it was) would be false. Then, if Aristotle could have lived (i.e., if he had it within his power to live) in Athens throughout this period, he could have rendered the last true proposition asserted by Plato false. On the other hand, if the last true proposition asserted by Plato is the proposition that the planets do not move in perfect circles, then Aristotle could not have rendered the last true proposition asserted by Plato false, since it was not within his power to produce any set of conditions sufficient for the falsity of this proposition.6

It is obvious that the proposition expressed by 'Aristotle could have rendered the last true proposition asserted by Plato false', is a proposition that we should be hard put to express without using the idiom of rendering propositions false, or, at least, without using some very similar idiom. We shall find this new idiom very useful in discussing the relation between free will (a thesis about abilities) and determinism (a thesis about certain propositions).

III

I shall now imagine a case in which a certain man, after due deliberation, refrained from performing a certain contemplated act. I shall then argue that, if determinism is true, then that man coul...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- PART I THE METAPHYSICAL ISSUES: FREE WILL AND CAUSAL DETERMINISM

- PART II THE ANALYSIS OF FREEDOM: COMPATIBILIST AND LIBERTARIAN ACCOUNTS

- PART III FREE WILL AND MORAL RESPONSIBILITY

- Selected Bibliography

- Contributors

- Index