eBook - ePub

Using an Inclusive Approach to Reduce School Exclusion

A Practitioner’s Handbook

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Using an Inclusive Approach to Reduce School Exclusion

A Practitioner’s Handbook

About this book

Clear and accessible, Using an Inclusive Approach to Reduce School Exclusion supports an inclusive approach to teaching and learning to help schools find ways to reduce exclusion and plan alternative approaches to managing the pathways of learners at risk.

Offering a summary of the contemporary context of DfE and school policy in England, this book considers:

- Statistics and perspectives from Ofsted

- The literature of exclusion and recent research into effective provision for learners with SEN

- The key factors underlying school exclusion

- Case studies and practical approaches alongside theory and research

- The impact of exclusion on learners at risk

Written by experienced practitioners, Using an Inclusive Approach to Reduce School Exclusion encourages a proactive approach to reducing exclusion through relatable scenarios and case studies. An essential toolkit to support the development of inclusive practice and reduce exclusion, this book is an invaluable resource for SENCOs, middle and senior leaders.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Using an Inclusive Approach to Reduce School Exclusion by Tristan Middleton,Lynda Kay in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Within the busy life of a school it is difficult to find the time to reflect upon education policy and legislation and debate the impact this has upon the classroom. The focus is more often upon mediating the policy within the everyday life of the school. This section of the book presents a distillation of policy and legislation in relation to inclusion and exclusion and aims to create the space for you to reflect upon how policy and legislation influence and frame practice in schools.

Chapter one

Background Context to Exclusion

Defining exclusion

Exclusion is the severest punishment that schools may implement and is frequently associated with disruptive or challenging behaviour (Kane, 2011; Munn, Lloyd and Cullen, 2000; Pomeroy, 2000). The Department for Education’s (DfE, 2017) statutory guidance uses the phrase “barred from school” within its explanation of exclusion (DfE, 2017, p. 56).

Thus, exclusion may be understood to be an enforced banishment from school (Kane, 2005; Cooper et al., 2000). Interestingly, Hodkinson (2012, p. 678) describes exclusion as a “forced absence of children from their classrooms” during which they are not perceived to be the responsibility of the teacher.

We were interested to note that in many discussions of exclusion within literature an explanation of how this term might be defined was not offered, hence the reader’s understanding of the concept appeared to be assumed.

Our definition of exclusion

Exclusion is a sanction which may be employed by schools, within the remit of school leaders and governors. Exclusion means that learners are banished from attending school or from learning or social activities with their peers within the school environment.

Schools may implement the sanction of exclusion as a fixed-period exclusion, in which a length of time for which the pupil is excluded is set out, or a permanent exclusion from the school’s roll. Within the sanction of fixed-period exclusion, schools may also exclude children and young people for a period of the day, such as for lunchtimes over an identified period of time. Statutory guidance for exclusion is provided by the DfE (2017). The term exclusion is used within sanctions of formal, informal and internal exclusion. Informal and internal exclusion will be explored within Chapter 2.

It should be noted that the sanction of exclusion is included within earlier legislation. Changes made to legislation over time included amendments made to terminology and the tariffs for fixed-period exclusions together with prohibiting indefinite exclusion. Legislation also placed a requirement upon schools to inform parents of exclusion together with the rationale for the decision and the right of appeal together with the appeal procedures was introduced. The tariff of 45 days across the school year was set out by the 1996 Education Act.

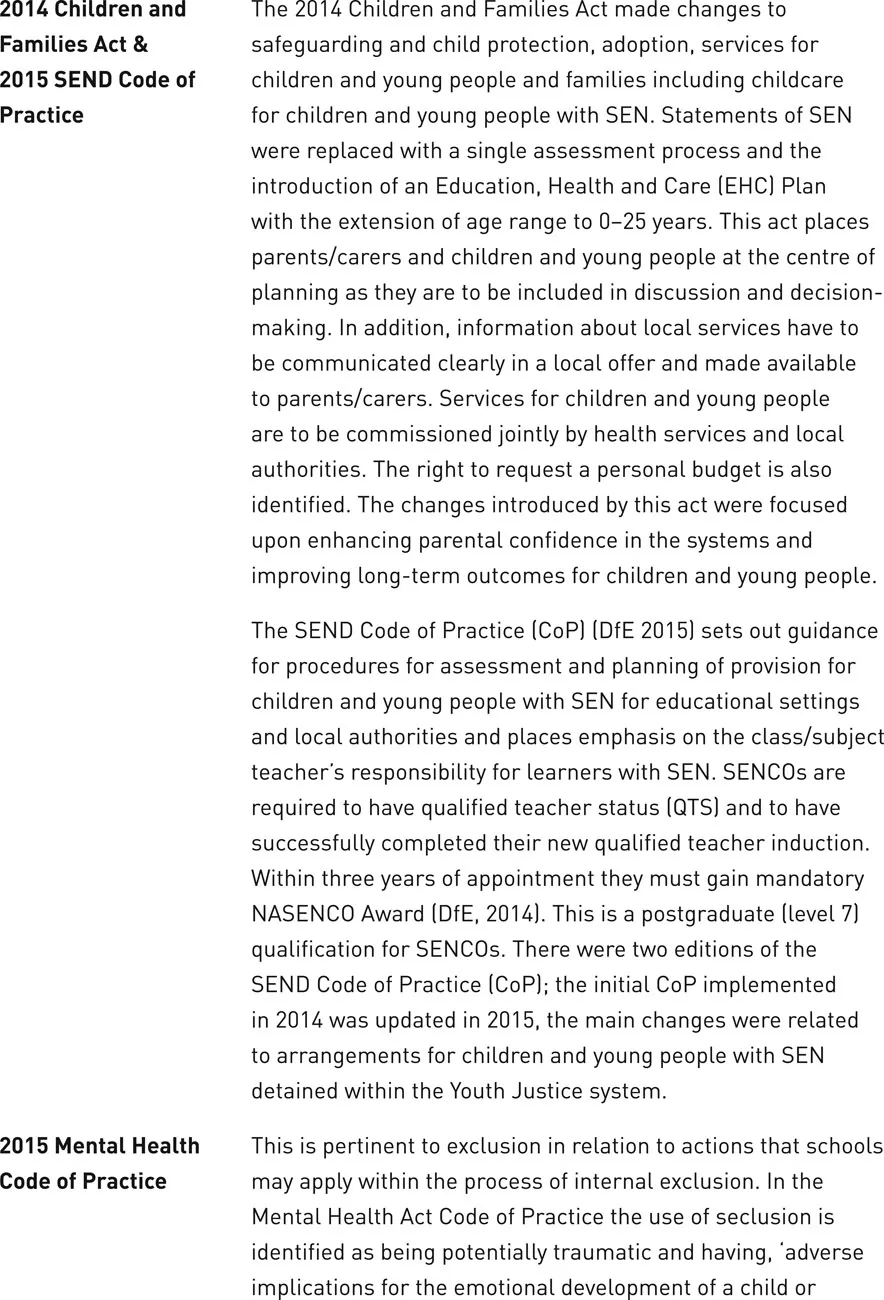

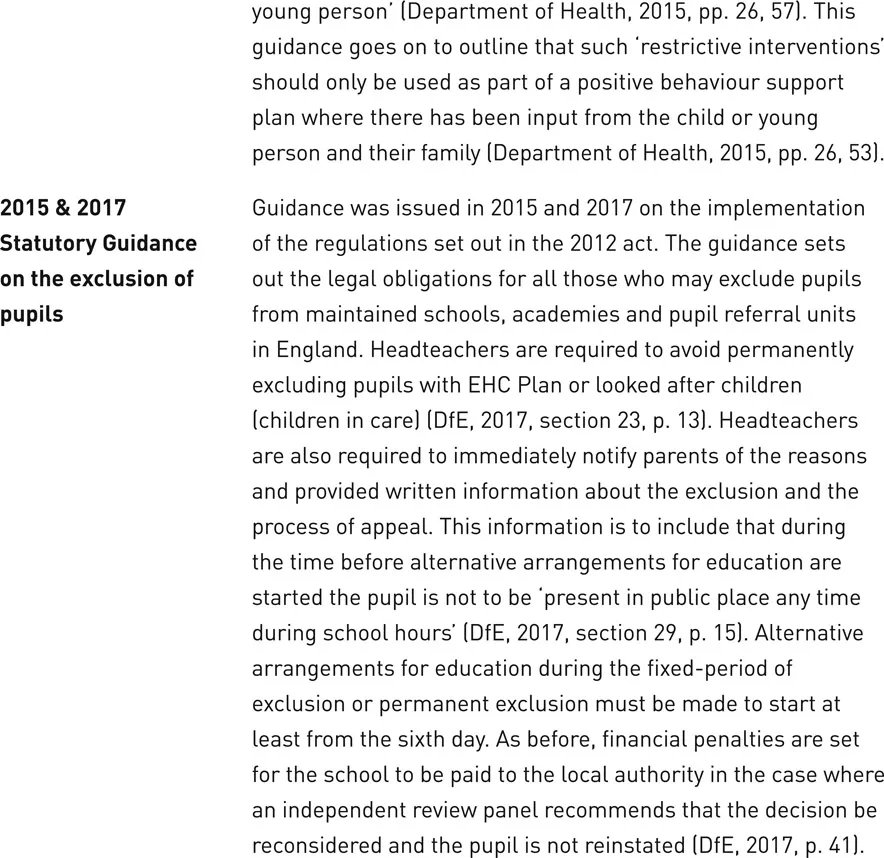

The information within the next section does not present a comprehensive review of the legislative framework. The focus of this flowchart is to present information pertinent to inclusion and exclusion.

The legislative framework influencing exclusion (1997–2018)

Education Policy in England 1997–2018: contextual influences upon inclusion and exclusion in schools

Policy is never monolithic but the tension between two aspects of policy – inclusion and exclusion – seem particularly stark.

(Kane, 2011, p. 16)

Education policy is subject to frequent change and the development of policy is influenced by a range of interacting influences drawn from components such as culture, social, political, economic, technological factors and religion. Forrester and Garratt (2016) and Ball (2013) propose that policy should be considered in terms of being a manifestation of the process of these interacting components rather than a fixed artefact, such as a policy document. It is important to note that education policy is inevitably closely related to the philosophy or beliefs of the proposers of the specific policy. Thus, in examining education policies which have been introduced over time, it is possible to identify a range of influencing beliefs, attitudes and values which influenced the development of those policies (Forrester and Garratt, 2016; Slee, 2011). It is also important to note that there may be variance in the discourse between the initial articulation of a policy and the enactment of that policy (Ball, 2013). There may be further changes observed as the policy is implemented, owing to the varying ways in which the policy is interpreted. Thus, the operationalisation of policy may not be the same as the purpose informing the initial policy (Forrester and Garratt, 2016; Ball, 2013; Slee, 2011).

So why are we including information and analysis of policy in this book about inclusion and exclusion?

This is because the wider policy context has an influence upon inclusion and exclusion through the changes which impact upon schools directly and the broader environment in which they operate (Brodie, 2001). Thus, many aspects of classroom practice are directly affected by local and national policies which have been influenced and developed by a range of factors as discussed in the previous paragraph.

Since at least the Second World War, the political discourse from all major parties has embodied the notion of a key purpose of schools being to educate children and young people for their future roles thus ensuring a strong competitive economy for the country (Waugh, 2015; Munn, Lloyd and Cullen, 2000). This suggests that academic standards have been held at the centre of political discourse in relation to education over a long period of time (Hayden, 1997). From 1997 onwards there have been frequent changes and reforms within education. Indeed, education policy remains at the forefront of policy within the UK and internationally owing to the link made between economic output and success within global markets. While many of the policies which have been implemented in England have been emulated in other countries, there have been influences from other countries upon English education policy (Ball, 2013). This includes the US (e.g. the notion of charter schools) and Sweden (e.g. free schools). Other influences have come from organisations such as the World Bank, Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the European Union (EU) through the inclusion of policies such as quasi-markets, quality assurance and the notion of education providing a business opportunity (Ball, 2013).

Knowledge economy

The link made within policy between education and economic output can be observed through the increasing use of the term ‘knowledge economy’ within discourse about education. Ball (2013) proposes that this term refers to the importance of the positive influence of knowledge upon learning, skills and organisation within invention and creativity and thus upon manufacturing. Ball suggests that the World Bank’s support for education within developing countries in order to develop a well-trained workforce to facilitate economic success exemplifies this notion of the link between knowledge and improved economic output being enacted in education policy. Education is thus being examined through the lens of economic enhancement. This is important to reflect upon in light of the policies which have sought to direct different aspects of schooling, such as curricula, standards and accountability.

Policy related to inclusion

Inclusive schooling is a social movement against educational exclusion.

(Slee and Allan, 2005, p. 15)

The term ‘inclusion’ arose from the social model of disability and was put forward by the disability movement (Hodkinson, 2012). The models of disability will be further discussed in Part II, Chapter 1. Inclusion plays a central role in government policy and is based on the principles of fairness, equality and human rights (Cowne, 2003; Alisauskas et al., 2011). This is a substantive area; lots of national and government policies have influenced the way inclusion has been shaped. We present here a short distillation of policy related to inclusion and SEND from 1997 onwards.

There were policies and legislation prior to 1997 which did ensure that local authorities assessed the needs of children and young people with SEN, provided mainstream support and offered parents and carers of these children and young people choices in where they were educated. However, it is interesting to note that within the 1981 Education Act local authorities were offered what may be considered to be an opportunity to continue segregation, owing to the inclusion of the requirement that integration should make efficient use of government resources and that it should not damage the progression of other children and young people (Denziloe and Dickens, 2004). This presents an interesting conceptual qualification in that neuro-typical children and young people’s needs could be seen as being prioritised over those with SEN.

This propensity was challenged within the 1994 UNESCO Salamanca Statement with the declaration of the rights of the child to be included in mainstream society and education. This is significant because it moved the discourse away from a dialogue of integration and placement of children and young people with SEN away from mainstream schools, and placed an emphasis upon challenging mainstream settings in relation to their acceptance, accommodation and participation of children and young people with SEN (Slee, 2011). Other elements which influenced the changes in government policy at this time include the civil rights movement which demanded equality for people with disabilities and challenged attitudes and processes within society, which were prejudicial together with changes within professional perceptions of the impact of segregation for children and young people with SEN (Forrester and Garratt, 2016; Hodkinson, 2016). International impetus for change was provided not only through the Salamanca Statement but also though other actions, such as an earlier convention, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) (1989) and the goals set within the Education for All programme (2000) (Forrester and Garratt, 2016).

From 1997, the reforms of education throughout the last decade of the twentieth century sought to widen inclusion within mainstream schools and increase the capacity of mainstream schools to meet the needs of children and young people with SEN (Hodkinson, 2016). The New Labour government policies were formulated within a social inclusion agenda based on the values of community, inclusion, fairness and social justice (Forrester and Garratt, 2016). The principles from the Salamanca Statement were embedded in law in the 2001 SEN and Disability Act (SENDA) (Smith et al., 2014). This policy remains the dominant legal policy around SEN; there have been adjustments to this in further legislation over time. It made illegal discrimination (active or accidental) which disadvantaged disabled people and required that reasonable adjustments be made in order to enable their fullest participation to the fullest degree possible. The dual system of mainstream and specialist provision continued within a discourse advocating wider inclusive practices (Forrester and Garratt, 2016). This has been argued to place limits upon inclusion and continue segregation (Hodkinson, 2016).

Concerns raised by Ofsted (2004) increased the focus upon the differences in the quality of provision for SEN in mainstream schools and influenced further policy developments which linked with the Every Child Matters (DfES, 2004) agenda to advocate closer collaboration between...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Foreword

- Poem

- How to use this book

- Introduction

- Part I

- Part II

- Part III

- Part IV

- Part V

- Index