![]()

1

Introduction

Early in the evening of spring 1995, I was walking up the crest of the hill overlooking the lakeside. All of a sudden I came upon the largest super moon I could have imagined. It hovered before me, seemingly sitting upon the trees on the other side of the lakeshore. I stopped and spent nearly half an hour just staring in complete awe at this glowing sphere of light.

My brain reinterpreted the perceived distance, making the moon appear so colossal that, if I reached out my hand far enough, I felt I would be able to brush against its dry and dusty surface. The illusion was so dramatic that these two different worlds appeared to come together, one almost seemingly colliding with the other. Something about this experience changed me. I have never been able to describe how, but the circumstances, and this encounter, redefined my horizons.

This experience occurred during the same period that I was taking my first class on Freud at university. I can date both of the two central themes of when my interest in space (or at least in the greater outer world) as well as my life-long passion with Freud began. The awareness of this extraordinary and unknown external world seemed to equally open the door to a correspondingly breath-taking inner universe. It was these two equivalent three-dimensional playgrounds of space that ignited my own imagination and inner life that these places beckoned to be explored and understood. Much of my life has been connected with exploring and understanding how these potential environments can be understood and developed.

If we return to the central question, why should you as the reader be interested in these areas I have been working to understand, such as space psychology; or why would you take any interest in a thinker from 100 years ago? What relevance is space or the psychological aspects of these issues to my everyday life or to me? All of these are valid points, but as I hope to illustrate, there is a subtle, but profound relationship to a much wider and deeper world that most people are not aware of and which does affect their everyday lives. The quality of our lives and even potentially to our very survival is predicated on properly resolving these questions. Not to put too fine a point on it, but getting these aspects right could very well determine the future of human beings on this planet or any others.

Figure 1.1 Photo of Super moon

![]()

2

Introduction II

Having had a tour of some of the key aspects and processes within our own internal worlds as well as having a clearer orientation to our cosmological context, we need to integrate the uniqueness of the time period that we are now inhabiting. When I was a child, the year 2017 for some reason seemed to be equated with the future. I am now 43 years old. Similar to my earlier sense, I feel that we are facing a complexity of change with the potential of irreversible impacts on a global and planetary level that really does require entirely new levels of integration of multi-disciplinary thinking. Issues like global warming, the extent of urbanisation, and the mismanagement of natural energy resources that could accelerate changes within our biosphere and our air, soil, and water quality have been described as ‘ecocide’ (Higgins, 2015). Why would this topic be of any interest to a psychologist and psychoanalyst?

The easiest answer is: what does one study if not consciousness and the practice and existential interaction of the study of minds in concert with their environments?

The first layer of understanding the importance of space travel is in its essence about properly connecting with our curiosity. What is on the other side? For the first sea explorers, the uncertainty and corresponding feelings of fear were probably equal factors to the risks and potential rewards of leaving everything behind to venture into new worlds to discover and conquer. Part of human psychology is to dream and to go experience different places. Most of the representations of the beginning literary and cinematic portraits of space travel and exploration contain an extraordinary intensity of anxiety and foreboding, if not the development of complete psychological breakdowns. Why might this consistent portrayal of psychological collapse and space exploration be the benchmark of the artistic imagination? These kinds of pessimistic cinematic and literary versions influence how the public sees the science fiction. It is possible the predominant views could forestall mission success sealing our collective scientific imagination in creating the ingredients for a successful mission (or not) into space? Technically, the severity of psychological anxiety states related to the deep unknown portrayed contain within them the ridding of the emotional states of panic and terror. These uncertainties are evacuated from the depths of the person’s internal world. These kinds of fears about the unknown external world then become projected to the external world in an attempt to have these gotten rid of. In the cinematic versions of space exploration, frequently these paranoid anxieties are expressed as embodied into the other team members, the living milieu, or the surrounding environments (spacecrafts or planetary environs). Looking at these questions about the unknown necessitates that we think about their implications in potentially new ways to take a step back from these processes to better appreciate how anxiety works, especially within the face of the absolute limits of space.

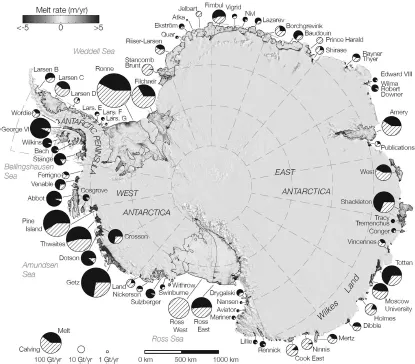

Figure 2.1 NASA melt map of Antarctica

![]()

3

Freud’s impact on my view of human nature

In the very early part of my career, I spent nearly two years working with Professor Mark Solms, when he was living in London, as his researcher helping him with the Standard Edition of Sigmund Freud’s Complete Psychological Works (24 volumes). Mark Solms is the father of neuro-psychoanalysis, and is an eminent psychoanalyst and Chair of Neuropsychology now in Cape Town, South Africa.

During this time, I worked on Freud’s complete body of psychological writings, reading through it twice and focusing on making updates to help modernise this work for the new revised edition. More precisely for this period of my life, I layered my day by starting off working either with new parents and neonates in the obstetrics hospital, while alternating with working at the UCL children’s crèche for my jobs that connected with my post-graduate training in early child development. I was undertaking the child development course of the first part of Tavistock’s psychotherapy training more years ago than I care to remember. After this was finished, I would take the unprecedented step of being one of the first Tavistock trainees to go over to the Anna Freud Centre (which is only down the street from Tavistock). At this point, however, because of a (perceived differences in technique between Klienian and Anna Freudian schools of psychotherapy) a huge rift in communication between the two groups was previously present between the Kleiniens’ (from the Tavistock) and the developmentalists from Anna Freud that is now beginning to thaw. In this way my interconnectivity going between each school was completely unique. After I finished at the Tavistock, I would go to the ‘Wednesday Anna Freud Child Analytic Lectures’ for the rest of the week; I would go straight to the Anna Freud Centre to do my evening work, and made myself a large pot of coffee to help with the late evenings of reading and editing my way through Freud’s collected works. By design and some help and support from my mentors, these experiences helped me start off the day deeply immersed in the psychological realities of early real life and trying to take these everyday human social interactions, like seeing new parents with their neonates (and I saw probably more than 2,000 parents) begin to make sense of having their own baby. This carried over into my other work environment where I had research opportunities every day, like hearing a three year old’s joke and studying the practical aspects of children’s social lives and play. By the evening I would bicycle up to the Anna Freud Clinic to work through all of Freud’s Standard Edition, and where I would work late into the evening.

These experiences provided a very deep appreciation in the subtlety of the developmental emotional lives of human beings through some of the worst difficulties. For instance, dealing with the impact of still births, psychotic postpartum depression, and stresses at home for the nursery children, to seeing when every aspect lined up beautifully and what differences this could make. These experiences really gave me a profound appreciation for our internal and emotional lives (even intergenerationally) that has impacted the rest of my professional and personal life thereafter. There is a magnificence, depth, and beauty to a full human being and a life that I still have never felt has yet been captured fully in literature or in art. I feel it is so much greater than I have yet to see it portrayed.

I felt so fortunate to have these different and really profound experiences. Every one of these layered experiences I have felt moved me and helped me grow into a deeper and more compassionate human being. Connected with reading Freud’s writing I have lived, breathed, and had Freud’s work saturate my being several times over. At least for this part of his writing, I think it is helpful to think one of the genius qualities of his own thinking was that he tried at some level to think about the entirety of his psychological works as part of a systematic examination of some of the biggest and most challenging questions human beings might be able to ask ourselves. However much of an achievement it was to read this part of his corpus, keep in mind that Freud wrote all of this work, plus his neuropsychological papers, and his correspondence which are actually from a corpus of work that is greater than all of the other literary output combined together. This really is a terrific accomplishment in volume, not to consider similarly how revolutionary some of his key words, seminal concepts, and thinking have been on every aspect of contemporary thought including writing and socialising with some of the greatest scientists and artists of history from his own time, which continues directly up to our own era.

Many have considered his book The Interpretation of Dreams to be his magnum opus. Within this volume, he explores the logic and unfathomable boundless architectures of human experience, memory, and the interaction of these with the instinct and psychical drives within the hidden world of sleep. All of these aspects of human life express the unconscious within the tapestry of interacting with the imprint of our social universe, which he described like a wax scribe indenting into our memory an imperfect recording our own subjective perspective of our everyday lives. These ingredients of human biology can help us better understand our human nature, especially as these influence our dreaming lives as well as our imaginations, remapping onto one and other to draw out themes and truths that seem to go beyond what we are consciously awa...