eBook - ePub

Oasis of Dreams

Teaching and Learning Peace in a Jewish-Palestinian Village in Israel

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Oasis of Dreams

Teaching and Learning Peace in a Jewish-Palestinian Village in Israel

About this book

Neve Shalom/Wahat Al-Salam (the Hebrew and Arabic words for Oasis of Peace) is a community founded by Jews and Palestinians that is aimed at demonstrating the possibilities for living in peace while maintaining their respective cultural heritages and languages. The village schools represent a unique educational experience: an opportunity for Jewish and Palestinian children to learn together in a Hebrew-Arabic bilingual, bicultural, binational setting. This book, a result of the author's nine year study of the schools in the village, explores the psychological and social dimensions of this important educational endeavor. Award-winning author Grace Feuerverger explores teaching and learning in schools as a sacred life journey, a quest toward liberation. Written for teacher/educators who wish to make a real difference in the lives of their students, this book speaks to everyone who finds themselves, as she did, on winding and often treacherous paths, longing to discover the meaning and potential in their professional lives at school. A child of Holocaust survivors, Feuerverger wrote this book to tell how schools can be transformed into magical places where miracles happen. In an era of narrow agendas of 'efficiency' and 'control', this book dares to suggest that education is and should always be about uplifting the human spirit.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Oasis of Dreams by Grace Feuerverger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education GeneralChapter One

An Oasis of Peace:

The Village of Neve Shalom/Wahat Al-Salam

Peace is every step,

—Thich Nhat Hahn

True to its name, the village of Neve Shalom/Wahat Al-Salam is a small “oasis of peace” within a deeply polarized country. Nestled on a rocky hilltop, it is surrounded by green fields full of dazzling wildflowers and olive groves (in winter) and by other collective rural settlements such as kibbutzim and moshavim.1 At the bottom of the hill several kilometers away is the Latrun Monastery and its vineyards, run by French Trappist monks who originally leased this land (a part of their holdings) to the village at the beginning of its existence in 1972.2

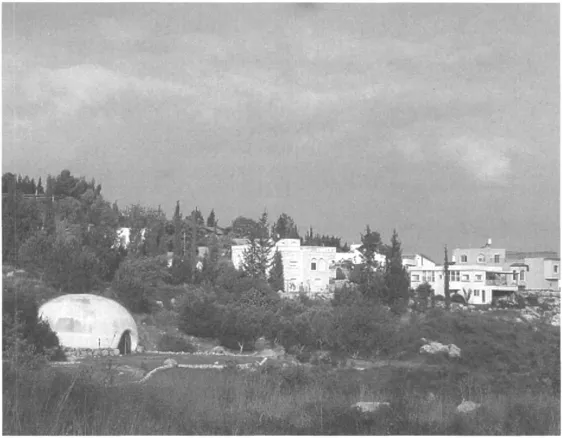

There are two means of access to the village: an old, picturesque dirt road, very bumpy and muddy in bad weather, and a newer asphalt road which meanders around fields and orchards. In the fields not far from this road, hidden by small trees, are the tents and sheep of a Bedouin family who has lived there since well before the village’s existence. As one enters the village, the first buildings encountered are the youth hostel, the guest house with separate free-standing rooms, and the dining hall. The view of the rolling and tranquil Ayalon Valley below is breathtaking. Looking westward on a very clear day at sunset, one can sometimes catch a glimpse of the Mediterranean Sea in the far distance. I cannot count the times I stood in silence marveling at that sublime sight. A small main road runs through the middle of the village with white houses and red roofs of different shapes and sizes on both sides. The houses reflect the diversity of the population. Some have a traditional Arabic style; others are a mixture of European and Middle Eastern design. Each home has an interesting garden filled with all sorts of spices, vegetables, fruit, and flowers. Many plants grow in abundance all over the village. The lushness of the vegetation and the colors and scents of the flowers (made possible through irrigation) are a magnificent sight, especially to one who was born and raised in North America north of the 49th parallel! In a lovely secluded corner of the hillside beneath the village houses and sheltered by an orchard is the “House of Silence” or Doumia/Sakina. It is a place of meditation, reflection and prayer. This white domeshaped building is a common sanctuary for all. (See Figures 1–1 and 1–2.)

Figure 1–1A view of the village of Neve Shalom/Wahat Al-Salam with the Doumia/Sakina at left. (Courtesy of NS/WAS. Used with permission.)

Figure 1–2The Bedouin family’s tent and sheep in the Ayalon Valley below the village. (Courtesy of the author.)

Approximately forty families and a number of single members comprise the population of the village. There is a waiting list of almost three hundred families who have applied to live in the village. The community is administered by a steering committee, the secretariat, which meets regularly once a week as well as whenever necessary. All matters requiring a decision of principle are considered by the plenum. The plenum consists of all residents, but only full members are entitled to vote. The plenum may return matters to the secretariat with the authority to make a final decision. The secretariat may decide to put matters to a vote in the plenum for a final decision. Once made, a final decision must be adhered to by the community. The community is governed by a constitution, which is reviewed from time to time. Several internal committees supervise various activities in the life of the community. All members of the secretariat and the committees are elected democratically each year. It is interesting to note that a balanced ratio of Jews and Arabs is observed throughout the community. The secretariat is always served by two Arabs and two Jewish members, plus the secretary. The secretary, who basically takes on the role of mayor of the village, is elected on merit and availability, but not strictly in rotation.

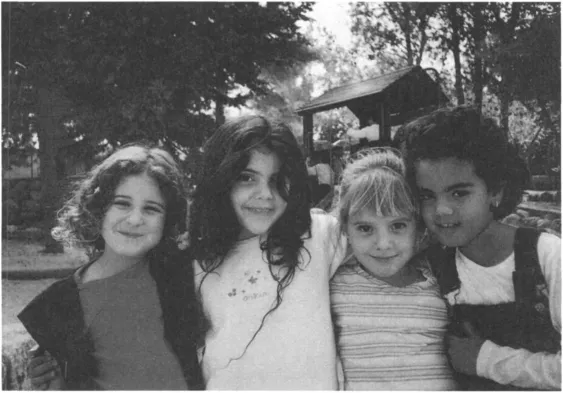

The elementary school is at the northeast side of the village; the entrance to the village is at the southwest border, about half a kilometer away. When I first arrived in 1991, the school consisted of three small buildings: a kindergarten, the multigrade elementary schoolhouse with a kitchen/staff room in the middle, and a bomb shelter3 which doubled as another classroom. In 1997 a new building was erected to accommodate the growing school population—an open plan design with large windows and much space, allowing a lot of freedom of movement. It is a closely knit environment; most of the students have at least one sibling attending along with them. Some of the teachers have their own children in the school. There are almost 300 children from kindergarten to grade six, with two kindergarten teachers and almost 30 elementary teachers. Each class has one Jewish and one Arab teacher; they work in a team-teaching mode. There is also a nursery and pre-kindergarten with about twenty toddlers. Many children are from the village, but a very large percentage of the children are bused into the school from nearby Jewish and Palestinian villages. One can sense that they feel very comfortable in the school. It is definitely their school (See Figure 1–3). I was immediately struck by their sense of ownership and the sense of empowerment which derives from it. Several village dogs are always sniffing around the entrance to the school and in the yard, waiting for the children to come out and play with them at recess, lunch, and at the end of the day. It is a noisy, gregarious, happy place.

Figure 1–3Four children on the school playground. (Courtesy of the author.)

This school is unique in its commitment to educating its students in a full Arabic-Hebrew bilingual, bicultural setting. The following box on page 5 is a brief statement of the school’s main educational goals.

During that first sojourn in 1991, Bob Mark, who is the school’s English teacher, was my host. He first took me to the preschool where the children were scampering about amid toys in the company of two very cheerful caregivers. Bob explained that one of the caregivers was Arab and the other one was Jewish; this was in fact the paradigm for all levels of schooling. In this way the children always have the opportunity to speak the language with which they are most familiar, and to identify with “their” teachers. Bob and I then walked up a stony pathway to the kindergarten. Inside, a very busy scene greeted us. The children, about fifteen of them, were involved in making decorations for a Christmas tree—a pine tree standing bare at the back of the room. Scissors and colored paper and tinsel sparkled in the air. Naomi, Bob’s daughter, approached us excitedly and showed me the little reindeer decorations and candy cane pictures that she was going to place on the tree. She whispered to me about how she was looking forward to the Christmas Eve party and how she had enjoyed the Hannukah celebration a week earlier. She asked me if I was going to attend. One of the teachers said, “I’m sure Grace will come to the party; it’s a very special event.” I was, of course, ecstatic at the prospect.

Educational Goals of the Neve Shalom/Wahat Al-Salam Primary School

Introduction

Consistent with its definition as a binational school* the NS/WAS Primary School strives to realize the principle of egalitarian co-existence between the two nations. There can be co-existence between members of the two peoples if, first of all, each child’s own identity is nurtured, and commensurate space is given for his/her language, culture and customs, so that the child feels on an equal footing with classmates of the other national group.

The fact that differences are accepted and seen as natural provides the basis for an educational system which emphasizes the uniqueness, and respects the freedom of choice, of every child.

The curriculum is designed to allow the primary school’s graduates to integrate into any high school in Israel, and therefore provides methodical study of all subjects learned in other schools: mathematics, English, nature, language, geography and others.

Both Jewish and Arab teachers teach in the school, with the guiding principle that each teacher instructs in his/her own language.

Goals

- To create an environment where the meeting between children of the two cultures is as natural as possible.

- To develop the child’s openness, sensitivity and tolerance towards his/her Jewish and Arab friends.

- To nurture, strengthen and foster each child’s identity.

- To deepen the child’s acquaintance with, and knowledge of, the cultural values of the group to which he/she belongs.

- To introduce the child to the literature, traditions and customs of the child from the other nation.

- To inculcate a knowledge of both Hebrew and Arabic as primary languages.

- To develop in the child an awareness of what is happening in Israel and throughout the world, while cultivating an understanding that events can be seen in more than one way.

- To develop independent learning by letting the child choose subjects for study.

- To allow the child to place particular emphasis on, and to deepen knowledge of, subjects which are dear to him/her.

- To impart knowledge and develop proficiency in primary subjects such as mathematics, nature, etc.

- To encourage the child’s impulse to creativity.

- To transform study into an enjoyable and positive experience.

The Management

* We use nation in reference to Jews and Palestinian Arabs, each of which see themselves as a distinct people with their own national culture, traditions and language.

Some of the children came up to me, curious to know who I was. In a small village, a stranger does not get lost. I spoke with the two teachers: one was a Moslem Arab; the other was Jewish. The person in charge of the decorating lesson was a teacher’s aide who was a Christian Arab. It should be noted that both Moslem and Christian Arabs, as well as Jews, live in Neve Shalom/Wahat Al-Salam. One part of the curriculum is devoted to the teaching of Jewish and Arab identity. Each child is taught to understand what his or her culture is all about and also learns about the other children’s cultures. The underlying principle is coexistence and tolerance and friendship, but not assimilation. Maintaining personal, social, and national identity is considered of utmost importance. Religion is taught separately, but there are joint discussions as well. The children learn about all the holidays of these three great religions during class time. They had just finished learning about Hannukah, the Jewish Festival of Lights, and prior to that about Milad-Un-Nabi, the birthday of the Islamic prophet Mohammed. And now it was time to prepare for Christmas. The children explained to me that it is important to respect each person’s religion. What I sensed was that in this school environment the holidays were enjoyed and treated equally, but that their religious meaning was taught separately. All the children were sharing their decorations and helping each other with the cutting and pasting tasks.

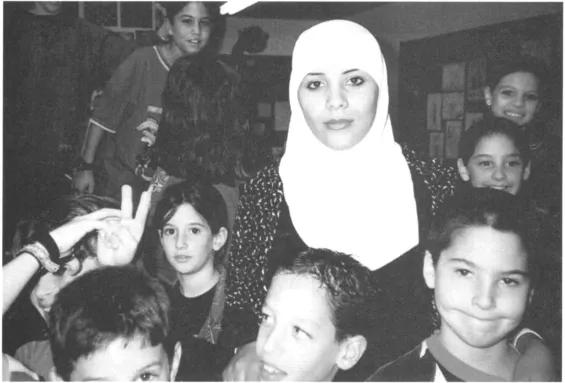

Then Bob and I left the kindergarten and walked to the elementary school not far away. It was a little stone building. A few dogs were ambling about. I walked in and was swept away in the flurry of classroom activities. My first impression was how cheerful and busy the atmosphere was—easygoing yet hardworking at the same time. I noticed a picture on the wall of Santa Claus that had been painted by one of the students. It was an unusual portrait that embodied, I think, the message of this village. There were gold Jewish stars on top of the Baba Noel and Arabic words on the bottom. The three religions were living peacefully together in this picture just as they were in the village. There was also a mural on the wall, created by the children, composed of drawings of Jerusalem from varying religious and cultural perspectives. For example, there was the Al-Aqsa Mosque along with the Arabic text describing it; the Western Wall with a text in Hebrew explaining its significance; and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, with an Arabic explanation. It was a sacred moment for me. (See Figure 1–4.)

Figure 1–4A teacher with her students in class. (Courtesy of the author.)

During that first sojourn, I also had the opportunity to visit the monks at the Latrun Monastery not far from the village. I sat in the lovely chapel meditating in the stillness of their vows of silence. I also had the occasion to taste (and purchase) their brandy, wine, and marmalade in the little shop that they run for tourists and local residents. In fact, I was lucky enough to accompany some of the villagers to the monastery for midnight mass on Christmas Eve. The church bells rang loudly in the pouring rain. Inside, the ceremony was conducted in Latin, French, Arabic, and Hebrew. After the mass, all the visitors were invited to partake in refreshments of hot mulled wine and cakes. During Christmas, the monks are allowed to speak, and the discussion between those who live in the monastery and the villagers was lively. What impressed me most was the deep respect each group had for one another’s religions: Jewish, Roman Catholic, Greek Orthodox, and Moslem. This experience spoke powerfully to me, I a child of Holocaust survivors.

Reflexive Ethnography on the Border of Hope

When freedom is the question, it is always time to begin,

—Maxine Greene (1988)

My personal and professional life has been greatly informed by the revolutionary landscape of Neve Shalom/Wahat Al-Salam. Indeed, the fieldwork experience has affected me in myriad ways and has allowed me to reflect more deeply on my life story. It is highly significant that I, the researcher in this study, was situated in the dual role of outsider/insider; as “outsider,” because I do not live in the village, but also as “insider” due to my being Jewish. Being an insider/outsider presupposes that there is a border—on one side you belong; on the other side you do not. Indeed, this book is all about borders: both imaginary and real, both positive and negative. My excursion into the landscape of Jewish-Palestinian coexistence and conflict resolution focuses on narratives of longing for and belonging to a homeland—the Jewish homeland of Israel that now exists and the Palestinian homeland that longs to be created. Both sides understand the troubling dimension of cultural displacement within their collective psyches. I adopted an ethnographic gaze on the life stories of my participants fueled by the desire arising from my own personal history to focus on this painful polarity of longing and belonging; the tension between personal and national aspirations of Jew and Palestinian in Israel. I wanted my “psychic signature” to be evident and for my interpretations to be understood through the embodiment of my own life story.

In contrast to the classical ethnographic approach, where the researcher is expunged from the text, the method of inquiry I offer here is more in concert with postmodern ethnographers who, in spite of having their qualms about the “authorial voice,” make themselves visible and sometimes even central to their research enterprise as a means of better understanding and interpreting the interaction of their past life experiences with the life experiences of their participants during their fieldwork, during their data analysis, and in the discussion of their findings (Behar, 1996; Britzman, 1998; Grimshaw, 1992; Marcus, 1998; Oakley, 1992; Rosaldo, 1993). My sense of “entitlement” to this reflexive approach comes from the research of James Banks, Ruth Behar, Michael Connelly, Elliot Eisner, Robert Coles, Jonathon Kozol, George Marcus, Clifford Geertz, Charlotte Davies, Norman Denzin, Maxine Greene, Yvonna Lincoln, and Renato Rosaldo to name only a few, who show that inquiring into another organizational life through embodied experiences does not compromise intellectual credibility. On the contrary, they emphasize that it strengthens the ways in which researchers construct their ethnographic text as well as the ways in which they read those of others. These scholars explain that reflexivity is inherent in social research at all stages and in all forms. For example, Charlotte Davies (1999) explains that this interest in reflexivity (the use of autobiography in ethnography) is a positive feature of ethnographic research, and indeed, a legitimate methodological approach. The central way in which ethnographers have established the validity of their written ethnographies— which Geertz (1988, p. 4–5) sees “as essentially the same as establishing their own authority, is through a variety of literary or rhetorical forms that demonstrate their having actually penetrated or been penetrated by ano...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. An Oasis of Peace: The Village of Neve Shalom/Wahat Al-Salam

- 2. A Community of Moral Education

- 3. The Pedagogy of Peace: Language Awareness in the Neve Shalom/Wahat Al-Salam Elementary School

- 4. Witnessing Trauma: The “School for Peace”

- 5. Portraits of Peace

- 6. Teaching Peace: The Power of Love, Art, and Imagination

- 7. The Dream of Peace

- Bibliography

- Index