- 512 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Modern research has revealed the Book of Changes to be a royal divination manual of the Zhou state (500100 BC). This new translation synthesizes the results of modern study, presenting the work in its historical context. The first book to render original Chinese rhymes into rhymed English.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Zhouyi by Richard Rutt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Ethnic Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

Ethnic StudiesPART I

Bronze Age China

XIA | |

c1560 BC | SHANG |

c1050 BC | ZHOU |

(1) Western Zhou (Zhouyi c825) | |

771 BC | (2) Eastern Zhou |

(1) Spring and Autumn (Confucius 551–479) | |

c450 BC | (2) Warring States |

221 BC | QIN (Burning of Books 213) |

207 BC | HAN |

THE CHINA OF ZHOUYI

1

The Background: Bronze Age China

The Book of Changes is often understood by Westerners in terms of what is commonly called ‘traditional’ Chinese culture but is really the culture of the last thousand years or less. Many of its features, including those that most attract Western attention, came into being some centuries after the Book of Changes was compiled. It is important to clear the mind of this sort of chinoiserie when approaching a Bronze Age text.

Although general histories of China usually begin with sections on the Bronze Age, they tend to concentrate on political and social structures, either omitting or merely outlining the domestic and circumstantial details that matter for understanding a book of oracles. Therefore a synopsis of the way of life that was the setting of Zhouyi is likely to be useful to non-specialist readers.

The Chinese have traditionally recounted the story of their prehistory in myths and legends1 telling of rulers who symbolize stages of civilization: Fuxi ‘tamer of animals (that is to say, sacrificial animals)’, for the hunting and food-gathering stage; Shennong, ‘divine husbandman’, for the agricultural stage; Huangdi, ‘yellow emperor’, for the time when boats, wheels, and ceramics were first made.

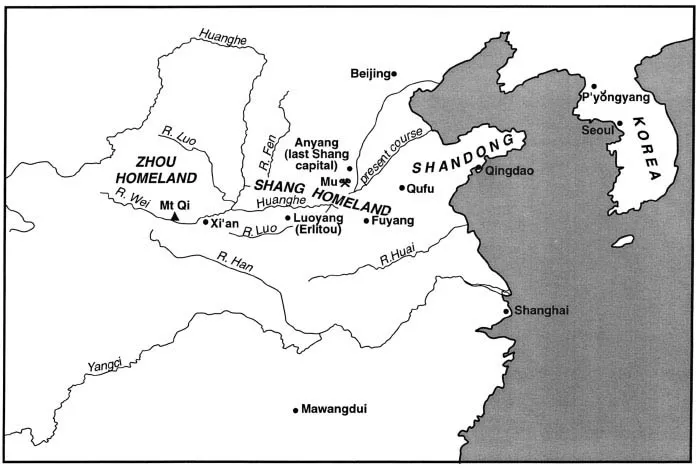

Historical evidence begins with the rich archaeological deposits from the Neolithic Age and earlier that have been found in the middle reaches of the Yellow River Basin. Next come the ample remains of people who inhabited Bronze Age settlements, such as one at Erlitou dating from the third millenium BC. These people are now referred to by many scholars as Xia, the name that since Han times has been supposed to be that of the first Chinese dynasty. Dynastic lists of Xia rulers appear to be legendary, and the legends about them are taken to be a mythopoesis from the succeeding periods, Shang and Zhou. Shang and Zhou were literate cultures and have left written remains.

These three ‘dynasties’, Xia, Shang and Zhou, extending from the end of the neolithic till the middle of the last millenium BC, form the period described here. Archaeological evidence is naturally more plentiful for the later centuries, and many modern scholars regard them less as successive dynasties than as three geographical, possibly racial, groups that became successively dominant in the whole region and were culturally interrelated. Highly developed bronze-casting was typical of the whole period, and although Chinese society was in many ways different from Bronze Age communities in the West – even their dates were not the same – this period is conventionally known as the Chinese Bronze Age.

The traditional dating for Shang (otherwise known as Yin, from the site of its last capital), is c1560–c1040 BC. Until the end of the nineteenth century Shang seemed as legendary as Xia; but archaeological discoveries have confirmed the written accounts to a surprising degree.

About 1040 BC Shang succumbed to Zhou, a people who lived at the Western end of the north Chinese plain, upstream among the mountains beyond the confluence of the Yellow River and the Wei. Before rebelling against the Shang king, the Zhou leaders owed allegiance to Shang and intermarried with the royal family. Their revolt ended with victory on the battlefield of Mu and the establishment of the Zhou dynasty, at a date which is not precisely known. No date in Chinese history before 841 BC is absolute, and scholars have favoured various dates for the establishment of Zhou, ranging from 1127 BC to 1018 BC. Since the bulk of modern opinion favours a later date, and the exact year is not crucial for understanding Zhouyi, it is assumed in this book that the conquest happened in the latter part of the eleventh century BC, probably in 1045.2

The leader of Zhou was Chang, known as Xibo ‘Viscount (or Elder) of the West’, but he died before the overthrow of Shang was complete. He was canonized as forefather of the new dynasty and posthumously given royal rank as King Wen, ‘civilizing monarch’. His son Fa defeated Shang conclusively, became the first Zhou ruler, and reigned for two years before he, too, died. Fa was canonized as King Wu, ‘military monarch’.

When King Wu died, his son and heir Cheng was still a minor. For some years Dan, younger son of King Wen and brother of King Wu, acted as regent for his nephew and came to play a leading part in establishing the dynasty. Dan is commonly referred to as Zhougong, ‘Duke of Zhou’, and Confucius, using this title for him, came to regard him as the ideal statesman of antiquity.

The Zhou dynasty lasted until 221 BC, and is divided into two parts. Up to 771 BC it is known as Western Zhou; after 771, when the capital was moved eastward from Hao (near modern Xi’an) to Luoyi (near modern Luoyang), it is called Eastern Zhou.

Eastern Zhou was a period of political disintegration, somewhat arbitrarily subdivided by historians into the Spring and Autumn Period and the Warring States Period. The Spring and Autumn period lasted till the middle of the fifth century BC, and is so called because it is recorded in Chunqiu ‘the Spring and Autumn Annals’, a chronicle covering the years 722–481 BC. This is also called the Period of the Hegemons, because while the Zhou king retained religious and ceremonial supremacy, effective power resided in the leaders of subsidiary states. Confucius (551–479 BC) lived at the end of the Spring and Autumn Period.

The Warring States Period, the second half of Eastern Zhou, lasted from the mid-fifth century to 221 BC. This title is also taken from a quasi-historical compilation, Zhan’guoce ‘Bamboo Records of the Warring States’, which contains stories about much of the period. Despite political and and military turmoil, Eastern Zhou was the period during which Chinese philosophy and literature matured, when Confucianism and Daoism were developed.

The material in Zhouyi dates from late Shang and Western Zhou. In those five or six hundred years there was much change, but our knowledge of detail is restricted, because written documents are few, and archaeology can discover only durable objects. Nevertheless, we know enough to help us avoid a significant degree of anachronism in translation.

The idea of China did not yet exist. We refer to Shang and Zhou as Chinese only because their culture was the beginning of what we now call Chinese culture and their dialects were the immediate ancestors of the Chinese language. Though they were highly civilized in most respects, their customs and morals were in some ways barbaric. Human sacrifice was only gradually discontinued after the beginning of Zhou; justice was summary and Zhouyi suggests that it often involved cruel mutilations. Confucian ideals of courtesy and benevolence had not as yet been named, though there were signs of a chivalric code among the aristocrats, at least in the conduct of battles.

The worst anachronism would be to read into Zhouyi moral attitudes that belong to later centuries. Arthur Waley wrote of this period:

… there was no conception of a human morality, of abstract virtues incumbent upon all men irrespective of their social standing, but only an insistence that people of a certain class should fulfil certain rites and maintain certain attitudes. The chief duty of the gentleman is to be dignified and so inspire respect in the common people … (even) ‘filial piety’ means tendence of the dead …3

Climate and terrain4

Shang originally ruled a relatively small area of the northern Chinese plain, drained by Huanghe, the Yellow River, and its tributaries. The area controlled by the dynasty gradually expanded, and by the end of Shang may have stretched as far south as the Yangzi River. By the end of Western Zhou, the kingdom was even larger.

Although the four seasons were clearly marked and the winter was severe, with notorious dark sandstorms at the end of it, the climate of the region was more benign than it is now. The people remained indoors during the winter months, and, as in most cultures, warfare was suspended. As anyone who has ever lived without electricity in a temperate climate must know, springtime brought intoxicating joy and relief, while autumn harvests gave opportunities for elaborate festivals. Spring and autumn were essential elements in the genesis of lyric poetry.

Scenery varied from the riverine plains to the high mountains. Much of the countryside was covered with trees and bamboo groves, growing as woodland and bush rather than thick forests. Trees included apricot, oak, willow, medlar and cypress, as well as conifers – a rich flora. Mulberry trees were esteemed for sericulture, and much planted near working folk’s houses. Lakes, marshes, streams and rivers provided ample water, though drought in summer was a constant fear. Throughout the period this luxuriant wild landscape was continuously being reclaimed for cereal agriculture: no trees were left growing in the tilled fields.

Political and social structure

Sinologists are divided on the subject of social structure. There has been much debate about the use of terms drawn from Western history, especially ‘feudalism’ and ‘slavery’, to describe early China. Feudalism, however, as it existed in Bronze Age China, has been aptly defined as ‘an institution of delegated authority, made up of contractual relationships’.5 Political organization, social structure and military chivalry had much in common with the feudalism of medieval Europe.

Power was based on heredity in noble families, and society was broadly divided between a ruling class and the peasants, though there was probably little difference in speech between peasant and aristocrat. Indeed, there is some evidence of kinship being recognized and maintained across economic and social boundaries, and it is known that aristocrats defeated in battle could be reduced to peasant status. We know little for certain about divisions within the two main groupings, or how many other groups there may have been. Zhouyi mentions, for instance, feiren ‘non-persons’, who may have formed a recognizable group, perhaps barbarians living among the Chinese, or barbarian slaves. Nor can we be quite sure what junzi were. Superficially the word means ‘prince’s sons’ but this meaning changed in the course of time. At first it was probably applied to minor royalty, who became a noble group. From this the word came to mean a man of princely or noble character, then to be used as an honorific term for one’s host or husband, and finally applied to the ‘gentleman’ or ‘superior man’ of the Confucian ideal.6

There was no concept of Empire, though the paramount ruler was called wang, ‘king’, and was able to give ‘fiefdoms’ to deserving subjects. These grants carried geographical titles whose significance changed over the centuries. The areas to which they were applied varied in size, and most were not large, though armies of thousands could be organized by some. Fiefdoms gave noble status, military and...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- About the Author

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of diagrams and tables

- Preface

- Romanization and Pronunciation

- PART I

- PART II

- PART III

- NOTES: References and further reading

- GLOSSARY of Chinese characters

- Index