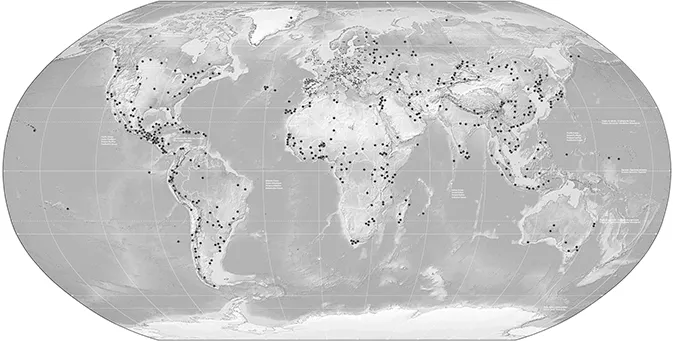

These are a few of the multiple ways that biosphere reserves (BRs) designated by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) have been described by academics, practitioners, and governing authorities. And yet, surprisingly, despite being part of an active, longstanding and growing global network of sites for research and action dedicated to biological and cultural conservation, and sustainable development (from 24 sites in 1974 to 701 sites in 2019), BRs are still relatively unknown or misunderstood. It is 35 years since the publication of the last books that featured the life and work of BRs globally (di Castri et al. 1984a; 1984b). Since then, a few UNESCO reports document the purpose of BRs and provide some case studies (e.g., UNESCO 2000; Garnier 2008); while some popular books have been published about BRs at a national level (e.g., Anon, 2006; German MAB National Committee 2005; Moreira-Muñoz and Borsdorf 2014; Reed et al. 2016). Hence, there is much scope to learn from an international network that provides platforms for interdisciplinary, longitudinal, and comparative research to better understand human-environment relations at multiple scales (Liu et al. 2007; Schultz et al. 2011).

Additionally, while sustainability scientists claim to have a strong focus on “transdisciplinarity” (e.g., Lang et al. 2012; Steelman et al. 2019) – where research questions and research strategies are developed in collaboration with communities outside of academia – these scientists give most attention to large modeling exercises or individual case studies (Rokaya et al. 2017). There has been no effort by sustainability scientists to establish a global network of research platforms from which lessons can be learned, although there have been some initiatives for specific types of environment, such as mountains (e.g., https://mountainsentinels.org/mountain-research/). These gaps suggest that there is much to be gained from documenting the successes and challenges within the World Network of BRs (WNBR). Such documentation can explain how practical lessons learned about conservation and sustainability can be shared and taken up across sites and scales, and may raise key questions about how best to translate sustainability science concepts into actions on the ground. To date, no compilation offers a global perspective through a common conceptual lens or an international platform of practice.

BRs share a set of common objectives: to be “sites of excellence” that support biodiversity conservation, sustainable development, and capacity building for research, education, and learning at regional scales. They are designated by UNESCO in geographic regions of global social-ecological significance. Local organizations in each region offer opportunities to “translate” high-level goals and multi-lateral environmental agreements (e.g., United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Convention on Biological Diversity, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change) into concrete strategies for application. BRs represent the most longstanding, organized, international, and intergovernmental network to support the aims of sustainability science, pursuing these aims using different approaches to implementation. It is important to underline that, unlike the worldwide collections of sites designated under the Ramsar and World Heritage Conventions, BRs are designated under “soft” legislation and are explicitly considered as a global network of sites (the WNBR). This global network is further organized by themes (e.g., mountains, islands and coasts) and by global regions. However, the concept, and implementation, of BRs have not always been well understood by scientists, governments, or even local residents where BRs have been established.

Objectives and structure of the book

This book has three objectives. The first is to document the evolution of BRs in countries in different parts of the world, demonstrating the great variety in how conservation, sustainable development, and scientific research and capacity building have been interpreted “on the ground” as the concept of BRs has itself evolved. Second, we aim to shed light on how UNESCO’s Man and Biosphere (MAB) Programme and its key tool for implementation – the WNBR – have sought to make operational the foundational concepts of sustainability science. Third, we describe key themes related to sustainability science (e.g., transdisciplinarity, governance, learning) and provide lessons from BR practices that describe opportunities for, and barriers to, translating sustainability science into sustainability in practice.

To meet these objectives, we have structured the book in three parts:

- Conceptual and practical foundations of the MAB Programme;

- Translation and transitions: the changing practices of biosphere reserves; and

- Lessons for sustainability science and sustainability in practice.

In Part I, two chapters set the stage for the examples that follow. Maureen G. Reed examines the antecedents of BRs and explains how they informed the “first generation” of BRs, those designated between 1974 and 1995. Meriem Bouamrane, Peter Dogsé, and Martin F. Price pick up the story, describing on-going efforts to strengthen the global network and to ensure that BRs become strategic players in addressing pressing global issues – biodiversity loss, climate change, and sustainable development.

In Part II, 15 short chapters articulate the experiences of implementation in countries across the WNBR. These chapters highlight how transitions in the global programme were interpreted and implemented in their national contexts. Contributors to this section include academics and practitioners, addressing questions such as: Within your national context, how has the understanding of BRs and their application changed over time?; How have BRs in your country connected with international MAB priorities, global action plans for BRs, and other BRs in the global network?; and What challenges continue to face BRs in your country as they seek to fulfil UNESCO criteria?

UNESCO divides the world into five regions: Latin America and the Caribbean; Europe and North America; Arab States; Africa; and Asia and the Pacific. This section includes at least two chapters from each region, with more emphasis placed in regions where there are more BRs. Among the contributions are chapters that describe experiences where BRs have been established since the 1970s (e.g., Ding and Qunli – China; Guevara Sada – Mexico; Mathevet and Cibien – France; Shaw et al. – Canada; Těšitel and Kušová – Czech Republic) and where they were established more recently (e.g., Chu et al. – Vietnam; Matar and Anthony – Lebanon; Gole et al. – Ethiopia; Pool-Stanvliet and Coetzer – South Africa). In some cases, countries with a longstanding involvement in the MAB Programme have reconfigured their national network as the requirements of the programme evolved (e.g., Price – UK; Bridgewater – Australia). Experiences documented in the national chapters demonstrate diverse strategies by which individual countries have contributed to this evolving global concept and tailored the concept according to the realities of their national contexts. Many chapters are co-authored by academic researchers and BR practitioners, providing both conceptual and practical insights into the application of the MAB Programme around the world.

To present this diversity, we circumnavigate the globe, beginning with BRs from Latin America and the Caribbean region, where some of the first biosphere reserves were established. Sergio Guevara Sada from Mexico explains how governments, communities, scientists and non-governmental organizations have worked together to support biological and cultural diversity and the wellbeing of local people. Next, Andrés Moreira-Muñoz, Francisca Carvajal, Sergio Elórtegui and Ricardo Rozzi describe the challenges to creating a national network of BRs in Chile, indicating that, if strong partnerships can be forged with government and non-governmental organizations, the ideals for BRs set out by UNESCO may come closer to reality.

Moving north, and into the Europe and North America region, we turn to experiences in Canada where Pamela Shaw, Monica Shore, Eleanor Haine-Bennett and Maureen G. Reed describe the history of local and governmental initiatives in relation to BRs. In particular, they highlight Canada’s recent efforts to meaningfully include Indigenous peoples in the governance of the program and in initiatives undertaken at the local level. Martin F. Price then explains how the United Kingdom’s BRs evolved, pointing out that the transition from “first generation” to “second generation” expectations for BRs provided an opportunity for serious reflection, withdrawal, and reconfiguration of BRs in the UK. As we move across Europe, we learn from Tomas Kjellqvist, Romina Rodela and Kari Lehtilä how different forms of knowledge have been used to justify the creation of new BRs in Sweden. From France, Raphaël Mathevet and Catherine Cibien write from the perspective of a country where national and local public authorities have had a strong role to play in establishing and implementing BRs. They trace this history, suggesting that more work can be done by using a participatory approach that brings together public action and local collective actions. The situation is different in the Czech Republic, where Jan Těšitel and Drahomira Kušová explain how different governance models emerged over different time periods, posing challenges as BRs compete in a multi-jurisdisctional landscape of competing designations.

Moving to the Arab States, Diane Matar and Brandon Anthony describe the challenges and contributions of BRs in war-torn Lebanon, emphasizing the importance of establishing partnerships beyond the Arab states and reviving traditional land management practices. From Egypt, we learn from Boshra Salem and Caroline King-Okumu the value of transdisciplinary research, as they explain how scientific research has been combined with participatory planning to advance the aims of BRs in Egypt. From the vantage point of Ethiopia, Tadesse Woldemariam Gole, Svane Bender, Rolf D. Sprung, Solomon Kebede, Teowdroes Kassahun, Alemayehu Negussie, Kerya Yasin, and Motuma Tafa explain the value of external donors and agencies for BRs located in a country without large means. Despite having very high conservation values, the external support of NGOs and development partners is still required because BRs are not part of the structure of government institutions. From South Africa, Ruida Pool-Stanvliet and Kaera Coetzer tell us how BRs have been introduced in the last 20 years. Although there is strong national support for the MAB Programme, they describe uneven implementation across BRs. Yet, despite the limitations, BRs continue to support sustainable land management in South Africa.

Turning to Asia and the Pacific, we learn from Japan, Vietnam, and China. Hiroyuki Matsuda, Shinsuke Nakamura, and Tetsu Sato write about the ebb and flow of the MAB Programme in Japan and describe the conditions that helped revitalize its BRs in the past decade. For Vietnam, Van Cuong Chu, Peter Dart, Nguyen Manh Ha, Vo Thi Minh Le, and Marc Hockings explain the challenges in introducing BRs in a country where top-down state management of protected areas has limited opportunities for cross-sectoral and local participation. China’s contribution to the WNBR has been longstanding. As described by Wang Ding and Han Qunli, China has been part of the MAB Programme since 1978, and one of its BRs was recognized by UNESCO in 2016 for its contributions to conservation and working with local communities for sustainable development. The last contribution in this section, by Peter Bridgewater, describes the Australian experience in four stages. As in the UK, new requirements introduced by the Statutory Framework in 1995 were viewed as an opportunity for renewal, resulting in withdrawals, reconfigurations and new BRs.

In Part III, six chapters focus on thematic lessons from practices in BRs for understanding the challenges and opportunities associated with sustainability science. Sustainability science has coalesced as a distinct field of inter- and transdisciplinary scholarship since the early 2000s (Kates 2011; Bettencourt and Kaur 2011). Indeed, the MAB Strategy 2015–25 sets out facilitation of sustainability science as a key element of one of its four strategic objectives. Defining sustainability science as “an integrated, problem-solving approach that draws on the full range of scientific, traditional and [I]ndigenous knowledge in a transdisciplinary way to identify, understand and address present and future economic, environmental, ethical and societal challenges related to sustainable development”, the Strategy declares that “BRs, particularly through their coordinators, managers and scientists, have key roles to play in operationalizing and mainstreaming sustainability science” (UNESCO 2017: 19).

Contributors to Part III reflect themes arising from this definition. Knowledge co-production and respectful “integration” from different cultural traditions is a key feature of these reflections. Marc Hockings and Ian Lilley, Diane Matar, Nigel Dudley, and Rob Markham consider processes of knowledge co-creation and cultural respect, describing strategies used in BRs to bring western scientific knowledge and local and Indigenous knowledge together to advance sustainability objectives in Lebanon, Croatia, Vietnam, and Australia. Tania Moreno-Ramos and Eduard Müller turn to similar issues from the experiences of their work in Latin America. They encourage us to think beyond “sustainable development” and to consider how BRs might support regenerative development in regions where ecological and cultural integrity have been challenging to maintain. Miren Onaindia, Cristina Herero, Alberto Hernández, José Vicente de Lucio, Antonio Pou, Juana Barber, Tomás Rueda, Bernardo Varela, Benedicta Rodríguez, and Aquilino Miguélez discuss how similar processes of knowledge co-creation have been established with local communities across Spanish BRs. The transfer of knowledge into action is explained in relation to diverse BRs in the Mediterranean Basin by Mario Torralba, María García-Martín, Cristina Quintas-Soriano, Franziska Wolpert, and Tobias Plieninger. Heike Walk, Vera Luthardt, and Benjamin Noelting discuss the critical roles that universities can play as partners with BRs, not just in research programs, but in creating curricula that offer students real-world opportunities to make a difference through learning-by-doing. In the last thematic contribution, Liette Vasseur reminds us that such efforts require time and on-going commitment. Under the umbrella of “ecosystem governance”, she encourages participants from local and Indigenous communities, universities, governments, and private and civil society sectors to “slow down the pace” to ensure meaningful, respectful and mutually-beneficial partnerships for sustainability. Finally, we close by offering some synthesis of the issues and themes raised by the book.